The Valley

Searching for the future in the most American city

Photographs by Ashley Gilbertson

No one knows why the Hohokam Indians vanished. They had carved hundreds of miles of canals in the Sonoran Desert with stone tools and channeled the waters of the Salt and Gila Rivers to irrigate their crops for a thousand years until, in the middle of the 15th century, because of social conflict or climate change—drought, floods—their technology became obsolete, their civilization collapsed, and the Hohokam scattered. Four hundred years later, when white settlers reached the territory of southern Arizona, they found the ruins of abandoned canals, cleared them out with shovels, and built crude weirs of trees and rocks across the Salt River to push water back into the desert. Aware of a lost civilization in the Valley, they named the new settlement Phoenix.

It grew around water. In 1911, Theodore Roosevelt stood on the steps of the Tempe Normal School, which, half a century later, would become Arizona State University, and declared that the soaring dam just completed in the Superstition Mountains upstream, established during his presidency and named after him, would provide enough water to allow 100,000 people to live in the Valley. There are now 5 million.

The Valley is one of the fastest-growing regions in America, where a developer decided to put a city of the future on a piece of virgin desert miles from anything. At night, from the air, the Phoenix metroplex looks like a glittering alien craft that has landed where the Earth is flat and wide enough to host it. The street grids and subdivisions spreading across retired farmland end only when they’re stopped by the borders of a tribal reservation or the dark folds of mountains, some of them surrounded on all sides by sprawl.

Phoenix makes you keenly aware of human artifice—its ingenuity and its fragility. The American lust for new things and new ideas, good and bad ones, is most palpable here in the West, but the dynamo that generates all the microchip factories and battery plants and downtown high-rises and master-planned suburbs runs so high that it suggests its own oblivion. New Yorkers and Chicagoans don’t wonder how long their cities will go on existing, but in Phoenix in August, when the heat has broken 110 degrees for a month straight, the desert golf courses and urban freeways give this civilization an air of impermanence, like a mirage composed of sheer hubris, and a surprising number of inhabitants begin to brood on its disappearance.

Growth keeps coming at a furious pace, despite decades of drought, and despite political extremism that makes every election a crisis threatening violence. Democracy is also a fragile artifice. It depends less on tradition and law than on the shifting contents of individual skulls—belief, virtue, restraint. Its durability under natural and human stress is being put to an intense test in the Valley. And because a vision of vanishing now haunts the whole country, Phoenix is a guide to our future.

1. The Conscience of Rusty Bowers

Among the white settlers who rebuilt the Hohokam canals were the Mormon ancestors of Rusty Bowers. In the 1890s, they settled in the town of Mesa, east of Phoenix and a few miles downstream from where the Verde River joins the Salt. In 1929, when Bowers’s mother was a little girl, she was taken to hear the Church president, believed to be a prophet. For the rest of her life, she would recall one thing he told the assembly: “I foresee the day when there will be lines of people leaving this valley because there is no water.”

The Valley’s several thousand square miles stretch from Mesa in the east to Buckeye in the west. Bowers lives on a hill at Mesa’s edge, about as far east as you can go before the Valley ends, in a pueblo-style house where he and his wife raised seven children. He is lean, with pale-blue eyes and a bald sunspotted head whose pinkish creases and scars in the copper light of a desert sunset give him the look of a figure carved from the sandstone around him. So his voice comes as a surprise—playful cadences edged with a husky sadness. He trained to be a painter, but instead he became one of the most powerful men in Arizona, a 17-year state legislator who rose to speaker of the House in 2019. The East Valley is conservative and so is Bowers, though he calls himself a “pinto”—a spotted horse—meaning capable of variations. When far-right House members demanded a 30 percent across-the-board budget cut, he made a deal with Democrats to cut far less, and found the experience one of the most liberating of his life. He believes that environmentalists worship Creation instead of its Creator, but he drives a Prius as well as a pickup.

In the late 2010s, the Arizona Republican Party began to worry Bowers with its growing radicalism: State meetings became vicious free-for-alls; extremists unseated mainstream conservatives. Still, he remained a member in good standing—appearing at events with Donald Trump during the president’s reelection campaign, handing out Trump flyers door-to-door—until the morning of Sunday, November 22, 2020.

Bowers and his wife had just arrived home from church when the Prius’s Bluetooth screen flashed WHITE HOUSE. Rudy Giuliani was calling, and soon afterward the freshly defeated president came on the line. As Bowers later recalled, there was the usual verbal backslapping, Trump telling him what a great guy he was and Bowers thanking Trump for helping with his own reelection. Then Giuliani got to the point. The election in Arizona had been riddled with fraud: piles of military ballots stolen and illegally cast, hundreds of thousands of illegal aliens and dead people voting, gross irregularities at the counting centers. Bowers had been fielding these stories from Republican colleagues and constituents and found nothing credible in them.

“Do you have proof of that?” Bowers asked.

“Yeah,” Giuliani replied.

“Do you have names?”

“Oh yeah.”

“I need proof, names, how they voted, and I need it on my desk.”

“Rudy,” Trump broke in, “give the man what he wants.”

Bowers sensed some further purpose to the call. “To what end? What’s the ask here?”

“Rudy, what’s the ask?” Trump echoed, as if he didn’t know.

America’s ex-mayor needed Bowers to convene a committee to investigate the evidence of fraud. Then, according to an “arcane” state law that had been brought to Giuliani’s attention by someone high up in Arizona Republican circles, the legislature could replace the state’s Biden electors with a pro-Trump slate.

The car was idling on the dirt driveway by a four-armed saguaro cactus. “That’s a new one,” Bowers said. “I’ve never heard that one before. You need to tell me more about that.”

Giuliani admitted that he personally wasn’t an expert on Arizona law, but he’d been told about a legal theory, which turned out to have come from a paper written by a 63-year-old state representative and avid Trump partisan named Mark Finchem, who was studying for a late-in-life master’s degree at the University of Arizona.

“We’re asking you to consider this,” Trump told Bowers.

“Mr. President …”

Bowers prayed a lot, about things large and small. But prayer doesn’t deliver instant answers. So that left conscience, which everyone is blessed with but some do their best to kill. An immense number of Trump-era Republican officeholders had killed theirs in moments like this one. Bowers, who considered the Constitution divinely inspired, felt his conscience rising up into his throat: Don’t do it. You’ve got to tell him you won’t do it.

“I swore an oath to the Constitution,” Bowers said.

“Well, you know,” Giuliani said, “we’re all Republicans, and we need to be working together.”

“Mr. President,” Bowers said, “I campaigned for you. I voted for you. The policies you put in did a lot of good. But I will do nothing illegal for you.”

“We’re asking you to consider this,” Trump again told Bowers.

At the end of November, Trump’s legal team flew to Phoenix and met with Republican legislators. Bowers asked Giuliani for proof of voter fraud. “We don’t have the evidence,” Giuliani said, “but we have a lot of theories.” The evidence never materialized, so the state party pushed the theories, colleagues in the legislature attacked Bowers on Twitter, and a crowd swarmed the capitol in December to denounce him. One of the most vocal protesters was a young Phoenix man a month away from world fame as the QAnon Shaman.

On December 4, Bowers wrote in his diary:

It is painful to have friends who have been such a help to me turn on me with such rancor. I may, in the eyes of men, not hold correct opinions or act according to their vision or convictions, but I do not take this current situation in a light manner, a fearful manner, or a vengeful manner. I do not want to be a winner by cheating … How else will I ever approach Him in the wilderness of life, knowing that I ask this guidance only to show myself a coward in defending the course He led me to take?

Caravans of trucks climbed the road to Bowers’s house with pro-Trump flags and video panels and loudspeakers blasting to his neighbors that he was corrupt, a traitor, a pervert, a pedophile. His daughter Kacey, who had struggled with alcoholism, was now dying, and the mob outside the house upset her. At one point, Bowers went out to face them and encountered a man in a Three Percenter T-shirt, with a semiautomatic pistol on his hip, screaming abuse. Bowers walked up close enough to grab the gun if the Three Percenter drew. “I see you brought your little pop gun,” he said. “You gonna shoot me? Yell all you want—don’t touch that gun.” He knew that it would take only one would-be patriot under the influence of hateful rhetoric to kill him. He would later tell the January 6 congressional committee: “The country is at a very delicate part where this veneer of civilization is thinner than my fingers pressed together.”

Emails poured in. On December 7, someone calling themselves hunnygun wrote:

FUCK YOU, YOUR RINO COCKSUCKING PIECE OF SHIT. STOP BEING SUCH A PUSSY AND GET BACK IN THERE. DECERTIFY THIS ELECTION OR, NOT ONLY WILL YOU NOT HAVE A FUTURE IN ARIZONA, I WILL PERSONALLY SEE TO IT THAT NO MEMBER OF YOUR FAMILY SEES A PEACEFUL DAY EVER AGAIN.

Three days before Christmas, Bowers was sitting on his patio when Trump called again—this time without his attorney, and with a strange message that might have been an attempt at self-exculpation. “I remember what you told me the last time we spoke,” Trump said. Bowers took this as a reference to his refusal to do anything illegal, which he repeated. “I get it,” Trump said. “I don’t want you to.” He thanked Bowers for his support during the campaign. “I hope your family has a merry Christmas.”

Kacey Bowers died at age 42 on January 28, 2021. COVID rules kept the family from her hospital bedside until her final hours. Bowers, a lay priest in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, gave his daughter a blessing, and at the very end, the family sang a hymn by John Henry Newman:

Lead, kindly Light, amid th’encircling gloom,

Lead thou me on!

The night is dark, and I am far from home,

Lead thou me on!

The gloom thickened. Bowers’s enemies launched an effort to recall him, with foot soldiers provided by the Trump youth organization Turning Point USA, which is headquartered in Phoenix. The recall failed, but it was an ill omen. That summer, a wildfire in the mountains destroyed the Bowers ranch, taking his library, his papers, and many of his paintings. In 2022, after Bowers testified before the January 6 committee in Washington, D.C., the state party censured him and another stream of abuse came to his doorstep. Term-limited in the House, he ran for a Senate seat just to let the party know that it couldn’t bully him out. He was demolished by a conspiracist with Trump’s backing. Bowers’s political career was over.

“What do you do?” Bowers said. “You stand up. That’s all you can do. You have to get back up. When we lost the place and saw the house was still burning and now there’s nothing there, gone, and to have 23-plus years of a fun place with the family to be gone—it’s hard. Is it the hardest? No. Not even close. I keep on my phone (I won’t play it for you) my last phone call from my daughter—how scared she was, a port came out of her neck, they were transporting her, she was bleeding all over, and she says: ‘Dad, please, help me, please!’ Compared to a phone call from the president, compared to your house burning down? So what? What do you do, Dad? Those are hard things. But they come at us all. They’re coming at us as a country … What do we do? You get up.”

Bowers went back to painting. He took a job with a Canadian water company called EPCOR. Water had obsessed him all his life—he did not want the prophet’s vision to come to pass on his watch. One bright day last October, we stood on the Granite Reef Diversion Dam a few miles from his house, where the two main water systems that nourish the Valley meet at the foot of Red Mountain, sacred to the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indians, whose reservation stood just across the dry bed of the river. Below the dam’s headgate three-foot carp thrashed in the turbulent water of the South Canal, and wild horses waded in the shallows upstream.

“What’s the politics of water here?” I asked.

Bowers laughed, incredulous. “Oh my gosh, that question. It’s everywhere. You’ve heard the dictum.”

I had heard the dictum from everyone in the Valley who thought about the subject. “Whiskey’s for drinking—”

“Water’s for fighting,” Bowers finished, and then he amended it: “Water’s for killing.”

2. The Heat Zone

Summer in the Valley for most of its inhabitants is like winter in Minnesota—or winter in Minnesota 20 years ago. People stay inside as much as possible and move only if absolutely necessary among the artificial sanctuaries of home, car, and work. Young professionals in the arts district emerge after dark to walk their dogs. When the sun is high, all human presence practically disappears from the streets, and you notice how few trees there are in Phoenix.

Frank Lloyd Wright disliked air-conditioning. During a visit to Taliesin West, the home and studio he built from desert stone in the 1930s on a hillside north of Phoenix, I read in his book The Natural House :

To me air conditioning is a dangerous circumstance. The extreme changes in temperature that tear down a building also tear down the human body … If you carry these contrasts too far too often, when you are cooled the heat becomes more unendurable; it becomes hotter and hotter outside as you get cooler and cooler inside.

The observation gets at the unnaturalness of the Valley, because its civilization is unthinkable without air-conditioning. But the massive amount of energy required to keep millions of people alive in traffic jams is simultaneously burning them up, because air-conditioning accounts for 4 percent of the world’s greenhouse-gas emissions, twice that of all aviation.

One morning last August, goaded by Wright and tired of air-conditioned driving, I decided to walk the mile from my hotel to an interview at the Maricopa County Recorder’s Office. Construction workers were sweating and hydrating on the site of a new high-rise. A few thin figures slouched on benches by the Valley Metro tracks. At a bus shelter, a woman lay on the sidewalk in some profound oblivion. After four blocks my skin was prickling and I thought about turning back for my rental car, but I couldn’t face suffocating at the wheel while I waited for the air to cool. By the time I reached the Recorder’s Office, I was having trouble thinking, as if I’d moved significantly closer to the sun.

Last summer—when the temperature reached at least 110 degrees on 55 days (above 110, people said, it all feels the same), and the midsummer monsoon rains never came, and Phoenix found itself an object of global horror—heat officially helped kill 644 people in Maricopa County. They were the elderly, the sick, the mentally ill, the isolated, the homeless, the addicted (methamphetamines cause dehydration and fentanyl impairs thought), and those too poor to own or fix or pay for air-conditioning, without which a dwelling can become unlivable within an hour. Even touching the pavement is dangerous. A woman named Annette Vasquez, waiting in line outside the NourishPHX food pantry, lifted her pant leg to show me a large patch of pink skin on her calf—the scar of a second-degree burn from a fall she’d taken during a heart attack in high heat after seven years on the streets.

[Read: The problem with ‘Why do people live in Phoenix?’]

It was 115 on the day I met Dr. Aneesh Narang at the emergency department of Banner–University Medical Center. He had already lost four or five patients to heatstroke over the summer and just treated one who was brought in with a body temperature of 106 degrees, struggling to breathe and unable to sweat. “Patients coming in at 108, 109 degrees—they’ve been in the heat for hours, they’re pretty much dead,” Narang said. “We try to cool them down as fast as we can.” The method is to strip off their clothes and immerse them in ice and tap water inside a disposable cadaver bag to get their temperature down to 100 degrees within 15 or 20 minutes. But even those who survive heatstroke risk organ failure and years of neurological problems.

Recently, a hyperthermic man had arrived at Narang’s emergency department lucid enough to speak. He had become homeless not long before and was having a hard time surviving in the heat—shelters weren’t open during the day, and he didn’t know how to find the city’s designated cooling centers. “I can’t keep up with this,” he told the doctor. “I can’t get enough water. I’m tired.”

Saving a homeless patient only to send him back out into the heat did not feel like a victory to Narang. “It’s a Band-Aid on a leaking dam,” he said. “We haven’t solved a deep-rooted issue here. We’re sending them back to an environment that got them here—that’s the sad part. The only change that helps that situation is ending homelessness. It’s a problem in a city that’ll get hotter and hotter every year. I’m not sure what it’ll look like in 2050.”

The mayor of Phoenix, Kate Gallego, has a degree in environmental science and has worked on water policy in the region. “We are trying to very much focus on becoming a more sustainable community,” she told me in her office at city hall. Her efforts include the appointment of one of the country’s first heat czars; zoning and tax policies to encourage housing built up rather than out (downtown Phoenix is a forest of cranes); a multibillion-dollar investment in wastewater recycling; solar-powered shipping containers used as cooling centers and temporary housing on city lots; and a shade campaign of trees, canopies, and public art on heavily walked streets.

But the homeless population of metro Phoenix has nearly doubled in the past six years amid a housing shortage, soaring rents, and NIMBYism; multifamily affordable housing remain dirty words in most Valley neighborhoods. Nor is there much a mayor can do about the rising heat. A scientific study published in May 2023 projected that a blackout during a five-day heat wave would kill nearly 1 percent of Phoenix’s population—about 13,000 people—and send 800,000 to emergency rooms.

Near the airport, on the treeless streets south of Jefferson and north of Grant, there was a no-man’s-land around the lonely tracks of the Union Pacific Railroad, with scrap metal and lumber yards, stacks of pallets, a food pantry, abandoned wheelchairs, tombstones scattered across a dirt cemetery, and the tents and tarps and belongings and trash of the homeless. I began to think of this area, in the dead center of the Valley, as the heat zone. It felt hotter than anywhere else, not just because of the pavement and lack of shade, but because this was where people who couldn’t escape the furnace came. Most were Latino or Black, many were past middle age, and they came to be near a gated 13-acre compound that offered meals, medical and dental care, information about housing, a postal address, and 900 beds for single adults.

Last summer, the homeless encampment outside the compound stretched for several desolate blocks—the kind of improvised shantytown I’ve seen in Manila and Lagos but not in the United States, and not when the temperature was 111 degrees. One day in August, with every bed inside the compound taken, 563 people in varying states of consciousness were living outside. I couldn’t understand what kept them from dying.

[Read: When will the Southwest become unlivable?]

Mary Gilbert Todd, in her early 60s, from Charleston, South Carolina, had a cot inside Respiro, a large pavilion where men slept on one side, women on the other. Before that she’d spent four years on the streets of Phoenix. Her face was sunburned, her upper teeth were missing, and she used a walker, but her eyes gleamed bright blue with energy.

“If you put a wet shirt on and wet your hair, it’s gonna be cool,” she told me cheerfully, poking with a fork at a cup of ramen. “In the daytime, you don’t wanna walk. It’s better, when you’re homeless, to find a nice, shady tree and build yourself a black tent that you can sleep in where there’s some breeze. The black, it may absorb more heat on the outside, but it’s going to provide more shade. Here you got the dry heat. You want to have an opening so wind can go through—something that the police aren’t going to notice too much. Because if you’re in a regular tent, they’re gonna come bust you, and if you’re sitting out in the open, they’re gonna come mess with you.” She said that she’d been busted for “urban camping” 600 times.

My guide around the compound was Amy Schwabenlender, who directs it with the wry, low-key indignation of a woman working every day in the trenches of a crisis that the country appears readier to complain about than solve. “It’s America—we don’t have to have homelessness,” she said. “We allow homelessness to happen. We—the big we.” The neighbors—a casket maker, an electric-parts supplier, the owners of a few decaying houses—blamed Schwabenlender for bringing the problem to their streets, as if she were the root cause of homelessness. In the face of a lawsuit, the city was clearing the encampment.

Schwabenlender had come to the Valley to get away from depressing Wisconsin winters. After her first night in a motel in Tempe, she went out to her car and found the window heat-glued to the door by its rubber seal. “What did I just do to myself?” she wondered. Now she lives in North Phoenix in a house with a yard and a pool, but she has seen enough misery to be a growth dissident.

“I don’t know why people want to live here,” she said, smiling faintly, her pallor set off by thick black hair. “We can’t have enough housing infrastructure for everyone who wants to live here. So why are we celebrating and encouraging more business? Why are we giving large corporations tax breaks to move here? How can we encourage people to come here when we don’t have enough housing for the people who are here, and we don’t have enough water? It doesn’t add up to me.”

While we were talking, a woman with a gray crew cut who was missing her left leg below the thigh rolled up to Schwabenlender in a wheelchair. She had just been released after a long prison term and had heard something that made her think she’d get a housing voucher by the end of the month.

Schwabenlender gave an experienced sigh. “There’s a waitlist of 4,000,” she told the woman.

On my way out of Respiro, I chatted with a staff member named Tanish Bates. I mentioned the woman I’d seen lying on the sidewalk by the bus shelter in the heat of the day—she had seemed beyond anyone’s reach. “Why didn’t you talk to her?” Bates asked. “For me, it’s a natural instinct—I’m going to try. You ask them, ‘What’s going on? What do you need? Do you need water? Should I call the fire department?’ Nothing beats failure but a try.” She gave me an encouraging pat. “Next time, ask yourself what you would want.”

Utterly shamed, I walked out into the heat zone. By the compound’s gate, a security guard stood gazing at the sky. A few lonely raindrops had begun to fall. “I been praying for rain,” she said. “I am so tired of looking at the sun.” People were lining up to spend an hour or two in a city cooling bus parked at the curb. Farther down Madison Street, the tents ended and street signs announced: THIS AREA IS CLOSED TO CAMPING TO ABATE A PUBLIC NUISANCE.

Every time I returned to Phoenix, I found fewer tents around the compound. The city was clearing the encampment block by block. In December, only a few stragglers remained outside the gate—the hardest cases, fading out on fentanyl or alert enough to get into fights. “They keep coming back,” said a skinny, shirtless young man named Brandon Bisson. “They’re like wild animals. They’ll keep coming back to where the food and resources are.” Homeless for a year, he was watering a pair of healthy red bougainvillea vines in front of a rotting house where he’d been given a room with his dog in exchange for labor. Bisson wanted a job working with animals.

“There’s no news story anymore,” Schwabenlender said as she greeted me in her office. The city had opened a campground where 15th Avenue met the railroad tracks, with shipping containers and tents behind screened fencing, and 41 people were now staying there. Others had been placed in hotels. But it was hard to keep tabs on where they ended up, and some people were still out on the street, in parks, in cars, under highway overpasses. “How do we keep the sense of urgency?” Schwabenlender murmured in her quizzical way, almost as if she were speaking to herself. “We didn’t end homelessness.” The housing waitlist for Maricopa County stood at 7,503. The heat was over for now.

3. Democracy and Water

Civilization in the Valley depends on solving the problem of water, but because this has to be done collectively, solving the problem of water depends on solving the problem of democracy. My visits left me with reasons to believe that human ingenuity is equal to the first task: dams, canals, wastewater recycling, underground storage, desalination, artificial intelligence. But I found at least as many reasons to doubt that we are equal to the second.

It’s easy to believe that the Valley could double its population when you’re flying in a helicopter over the dams of the Salt River Project, the public utility whose lakes hold more than 2 million acre-feet—650 trillion gallons—of water; and when Mayor Gallego is describing Phoenix’s multibillion-dollar plan to recycle huge quantities of wastewater; and when Stephen Roe Lewis, the leader of the Gila River Indian Community, is walking through a recharged wetland that not long ago had been barren desert, pointing out the indigenous willows and cattails whose fibers are woven into traditional bracelets like the one around his wrist.

But when you see that nothing is left of the mighty Colorado River as it approaches the Mexican border but dirt and scrub; and when you drive by a road sign south of the Valley that says EARTH FISSURES POSSIBLE because the water table is dropping four feet a year; and when sprinklers are watering someone’s lawn in Scottsdale in the rain—then the prophet’s vision feels a little closer.

American sprawl across the land of the disappeared Hohokam looks flimsy and flat and monotonous amid the desert’s sublime Cretaceous humps. But sprawl is also the sight of ordinary people reaching for freedom in 2,000 square feet on a quarter acre. Growth is an orthodox faith in the Valley, as if the only alternative is slow death.

Once, I was driving through the desert of far-northern Phoenix with Dave Roberts, the retired head of water policy for the Salt River Project. The highway passed a concrete fortress rising in the distance, a giant construction site with a dozen cranes grasping the sky. The Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s three plants would employ 6,000 people; they would also consume billions of gallons of Phoenix’s water every year. Roberts filled in the empty space around the site: “All this desert land will be apartments, homes, golf courses, and who knows what—Costcos. There’s going to be malls out here. Gobs of people.” As long as people in places like Louisiana and Mississippi wanted to seek a better life in the Valley, who was he to tell them to stay away? A better life was the whole point of growth.

I asked Roberts, an intensely practical man, if he ever experienced apocalyptic visions of a dried-up Valley vanishing.

“We have three things that the Hohokam didn’t,” he said—pumping, storage (behind dams and underground), and recycling. When I mentioned this to Rusty Bowers, I couldn’t remember the third thing, and he interjected: “Prayer.” I offered that the Hohokam had probably been praying for water too. “I bet they were,” Bowers said. “And the Lord says, ‘Okay. I could go Bing! But that’s not how I work. Go out there and work, and we’ll figure this thing out together.’ ”

This famously libertarian place has a history of collective action on water. Thanks to the bipartisan efforts of the 20th century—the federal dams built in the early 1900s; the 330-mile canal that brought Colorado River water to the Valley in the late 20th century; a 1980 law regulating development in Arizona’s metro regions so they’d conserve groundwater, which cannot be replaced—Phoenix has a lot of water. But two things have happened in this century: a once-in-a-millennium drought set in, and the political will to act collectively dried up. “The legislature has become more and more partisan,” Kathleen Ferris, an architect of the 1980 law, told me. “And there’s a whole lot of denial.”

At some point, the civilization here stopped figuring this thing out together. The 1980 groundwater law, which required builders in regulated metro areas like the Valley to ensure a 100-year supply, left groundwater unregulated in small developments and across rural Arizona. In the mid-1990s, the legislature cut loopholes into the 100-year requirement. The God-given right to pursue happiness and wealth pushed housing farther out into the desert, beyond the reach of the Valley’s municipal water systems, onto groundwater. In the unregulated rural hinterland, megafarms of out-of-state and foreign agribusinesses began to pump enormous quantities of groundwater. The water table around the state was sinking, and the Colorado River was drying up.

Ferris imagined a grim future. Without new regulation, she said, “we will have land subsidence, roads cracking, destroying infrastructure, and in some cases people’s taps going dry.” The crisis wouldn’t hit the water-rich Phoenix metroplex first. “It’s going to be on the fringes, and all the people who allowed themselves to grow there are going to be really unhappy when they find out there’s no water.”

Most people in the Valley come from somewhere else, and John Hornewer came from Chicago. One summer in the early 1990s, when he was about 25, he went for a hike in the Hellsgate Wilderness, 75 miles northeast of Phoenix, and got lost. He ran out of water and couldn’t find a stream. When he grew too weak to carry his backpack, he abandoned it. His eyes began to throb; every muscle hurt; even breathing hurt. He sank to his knees, his face hit the ground, and as the flies buzzed around he thought: Just stop my heart. He was saved by campers, who found him and drove him the 20 miles he’d wandered from his car.

Almost dying from dehydration changed Hornewer’s life. “I take water very seriously,” he told me. “I’m passionate about water.”

In the late ’90s, Hornewer and his wife bought two and a half acres several miles up a dirt road in Rio Verde Foothills, a small community on the northeastern edge of the Valley. To the southwest, the city of Scottsdale ends and unincorporated Maricopa County starts where the golf courses give way to mesquite and the paved roads turn to dirt. Over the years, the desert around the Hornewers was filled in by people who wanted space and quiet and couldn’t afford Scottsdale.

Seeing a need, Hornewer started a business hauling potable water, filling his 6,000-gallon trucks with metered water at a Scottsdale standpipe and selling it to people in Rio Verde with dry wells or none at all. What kept Rio Verde cheaper than Scottsdale was the lack of an assured water supply. Wildcat builders, exploiting a gap in the 1980 law, didn’t tell buyers there wasn’t one, or the buyers didn’t ask. Meanwhile, the water table under Rio Verde was dropping. One of Hornewer’s neighbors hit water at 450 feet; another neighbor 150 feet away spent $60,000 on a 1,000-foot well that came up dry.

Hornewer wears his gray hair shoulder-length and has the face of a man trying to keep his inherent good nature from reaching its limit. In the past few years, he began to warn his Rio Verde customers that Scottsdale’s water would not always be there for them, because it came to Scottsdale by canal from the diminishing Colorado River. “We got rain a couple of weeks ago—everything’s good!” his customers would say, not wanting to admit that climate change was causing a drought. He urged the community to form a water district—a local government entity that would allow Rio Verde to bring in water from a basin west of the Valley. The idea was killed by a county supervisor who had done legal work for a giant Saudi farm that grew alfalfa on leased state land, and who pushed for EPCOR, the private Canadian utility, to service Rio Verde. The county kept issuing building permits, and the wildcatters kept putting up houses where there was no water. When the mayor of Scottsdale announced that, as of January 1, 2023, his city would stop selling its water to Rio Verde, Hornewer wasn’t surprised.

Suddenly, he had to drive five hours round trip to fill his trucks in Apache Junction, 50 miles away. The price of hauled water went from four cents a gallon to 11—the most expensive water anywhere in the country. Rio Verde fell into an uproar. The haves with wet wells were pitted against the have-nots with hauled water. Residents tried to sell and get out; town meetings became shouting matches with physical threats; Nextdoor turned septic. As soon as water was scarce, disinformation flowed.

In the middle of it all, Hornewer tried to explain to his customers why his prices had basically tripled. Some of them accused him of trying to get their wells capped and enrich his business. He became so discouraged that he thought of getting out of hauling water.

“I don’t have to argue with people anymore about whether we’re in a drought—they got that figured out,” he told me. “It would be nice if people could think ahead that they’re going to get hit on the head with a brick before it hits you on the head. After what I saw, I think the wars have just begun, to be honest with you. You’d think water would be unifying, but it’s not. Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting.”

One of Hornewer’s customers is a retiree from Buffalo named Rosemary Carroll, who moved to Rio Verde in 2020 to rescue donkeys. The animals arrived abused and broken at the small ranch where she lived by herself, and she calmed them by reading to them, getting them used to the sound of her voice, then nursed them back to health until she could find them a good home. Unfairly maligned as dumb beasts of burden, donkeys are thoughtful, affectionate animals—Carroll called them “equine dogs.”

After Scottsdale cut off Rio Verde on the first day of 2023, she repaired her defunct well, but she and her two dozen donkeys still relied on Hornewer’s hauled water. To keep her use down in the brutal heat, she took one quick shower a week, bought more clothes at Goodwill rather than wash clothes she owned, left barrels under her scuppers to catch any rainwater, and put double-lock valves, timers, and alarms on her hoses. Seeing water dripping out of a hose into the dirt filled her with despair. In the mornings, she rode around the ranch with a pail of water in a wagon pulled by a donkey and refilled the dishes she’d left out for rabbits and quail. Carroll tried to avoid the ugly politics of Rio Verde’s water. She just wanted to keep her donkeys alive, though an aged one died from heat.

And all summer long, she heard the sound of hammering. “The people keep coming, the buildings keep coming, and there’s no long-term solution,” Carroll told me, taking a break in the shade of her toolshed.

Sometimes on very hot days when she was shoveling donkey manure, Carroll gazed out over her ranch and her neighbors’ rooftops toward the soft brown hills and imagined some future civilization coming upon this place, finding the remains of stucco walls, puzzling over the metal fragments of solar panels, wondering what happened to the people who once lived here.

“If we thought Rio Verde was a big problem,” Kathleen Ferris said, “imagine if you have a city of 100,000 homes.”

An hour’s drive west from Phoenix on I-10, past truck stops and the massive skeletons of future warehouses, you reach Buckeye. In 2000, 6,500 people lived in what was then a farm town with one gas station. Now it’s 114,000, and by 2040 it’s expected to reach 300,000. The city’s much-publicized goal, for which I never heard a convincing rationale, is to pass 1 million residents and become “the next Phoenix.” To accommodate them all, Buckeye has annexed its way to 642 square miles—more land than the original Phoenix.

In the office of Mayor Eric Orsborn, propped up in a corner, is a gold-plated shovel with TERAVALIS on the handle. Teravalis, billed as the “City of the Future,” is the Howard Hughes Corporation’s planned community of 100,000 houses. Its several hundred thousand residents would put Buckeye well on its way to 1 million.

[Olga Khazan: Why people won’t stop moving to the Sun Belt]

I set out to find Teravalis. I drove from the town center north of the interstate on Sun Valley Parkway, with the White Tank Mountains to the right and raw desert all around. I was still in Buckeye—this was recently annexed land—but there was nothing here except road signs with no roads, a few tumbledown dwellings belonging to ranch hands, and one lonely steer. Mile after mile went by, until I began to think I’d made a mistake. Then, on the left side of the highway, I spotted a small billboard planted in a field of graded dirt beside a clump of saguaros and mesquite that seemed to have been installed for aesthetic purposes. This was Teravalis.

Some subdivisions in the Valley are so well designed and built—there’s one in Buckeye called Verrado—they seem to have grown up naturally over time like a small town; others roll on in an endless sea of red-tile sameness that can bring on nausea. But when I saw the acres of empty desert that would become the City of the Future, I didn’t know whether to be inspired by the developer’s imagination or appalled by his madness, like Fitzcarraldo hauling a ship over the Andes, or Howard Hughes himself beset by some demented vision that the open spaces of the New World arouse in willful men bent on conquest. And Teravalis has almost no water.

In her first State of the State address last year as Arizona’s governor after narrowly defeating Kari Lake, Katie Hobbs revealed that her predecessor, Doug Ducey, had buried a study showing that parts of the Valley, including Buckeye, had fallen short of the required 100-year supply of groundwater. Because of growth, all the supply had been allocated; there was none left to spare. In June 2023, Hobbs announced a moratorium on new subdivisions that depended on groundwater.

The national media declared that Phoenix had run dry, that the Valley’s fantastic growth was over. This wasn’t true but, as Ferris warned, the edge communities that had grown on the cheap by pumping groundwater would need to find other sources. Only 5,000 of Teravalis’s planned units had received certificates of assured water supply. The moratorium halted the other 95,000, and it wasn’t obvious where Teravalis and Buckeye would find new water. Sarah Porter, who directs a water think tank at Arizona State, once gave a talk to a West Valley community group that included Buckeye’s Mayor Orsborn. She calculated how much water it would take for his city to be the next Phoenix: nearly 100 billion gallons every year. Her audience did not seem to take in what she was saying.

Orsborn, who also owns a construction company, is an irrepressible booster of the next Phoenix. He described to me the plans for finding more water to keep Buckeye growing. Farmland in the brackish south of town could be retired for housing. Water from a basin west of the Valley could be piped to much of Buckeye, and to Teravalis. Buckeye could negotiate for recycled wastewater and other sources from Phoenix. (The two cities have been haggling over water in and out of court for almost a century, with Phoenix in the superior position; another water dictum says, “Better upstream with a shovel than downstream with a lawyer.”) And there was the radical idea of bringing desalinated water up from the Gulf of California through Mexico. All of it would cost a lot of money.

“What we’ve tried to do is say, ‘Don’t panic,’ ” the mayor told me. “We have water, and we have a plan for more water.”

At certain moments in the Valley, and this was one, ingenuity took the sound and shape of an elaborate defense against the truth.

When Kari Lake ran for governor in 2022, everyone knew her position on transgenderism and no one knew her position on water, because she barely had one. The subject didn’t turn out voters or decide elections; it was too boring and complicated to excite extremists. Water was more parochial than partisan. It could pit an older city with earlier rights against the growing needs of a newer one, or a corporate megafarm against a nearby homesteader, or Native Americans downstream against Mormon farmers upstream. Stephen Roe Lewis, the leader of the Gila River Indian Community, described years of court battles and federal legislation that finally restored his tribe’s water rights, which were stolen 150 years ago. The community, desperately poor in other ways, had grown rich enough in water that nearby cities and developments were lining up to buy it.

As long as these fights took place in the old, relatively sane world of corrupt politicians, rapacious corporations, overpaid lawyers, and shortsighted homeowners, solutions would usually be possible. But if, like almost everything else in American politics, water turned deeply partisan and ideological, contaminated by conspiracy theories and poisoned with memes, then preserving this drought-stricken civilization would get a lot harder, like trying to solve a Rubik’s Cube while fending off a swarm of wasps that you might be hallucinating.

4. Sunshine Patriots

They descended the escalators of the Phoenix Convention Center under giant signs—SAVE AMERICA, BIG GOV SUCKS, PARTY LIKE IT’S 1776—past tables explaining the 9/11 conspiracy and the Catholic Church conspiracy and the rigged-election conspiracy; tables advertising conservative colleges, America’s Leading Non-Woke Job Board, an anti-abortion ultrasound charity called PreBorn!, a $3,000 vibration plate for back pain, and the One and Only Patriot Owned Infrared Roasted Coffee Company, into the main hall, where music was throbbing, revving up the house for the start of the largest multiday right-wing jamboree in American history.

In the undersea-blue light, I found an empty chair next to a pair of friendly college boys with neat blond haircuts. John was studying in North Carolina for a future in corporate law; Josh was at Auburn, in Alabama, about to join the Marines. “We came all the way here to take back the country,” John said. From what or whom? He eagerly ticked off the answers: from the New York lady crook who was suing Donald Trump; from the inside-job cops who lured the J6 patriots into the Capitol; from the two-tier justice system, the corrupt Biden family, illegal immigrants, the deep state.

The students weren’t repelled by the media badge hanging from my neck—it seemed to impress them. But within 90 seconds, the knowledge that these youths and I inhabited unbridgeable realms of truth plunged me into a surprising sadness. One level below, boredom waited—the deepest mood of American politics, disabling, nihilistic, more destructive than rage, the final response to an impasse that resists every effort of reason.

I turned to the stage. Flames and smoke and roving searchlights were announcing the master of ceremonies.

“Welcome to AmericaFest, everybody. It’s great to be here in Phoenix, Arizona, it’s just great.”

Charlie Kirk—lanky in a patriotic blue suit and red tie, stiff-haired, square-faced, hooded-eyed—is the 30-year-old founder of Turning Point USA, the lucrative right-wing youth organization. In 2018, it moved its headquarters to the Valley, where Kirk lives in a $4.8 million estate on the grounds of a gated country club whose price of entry starts at $500,000. In December, 14,000 young people from all 50 states as well as 14 other countries converged on Phoenix for Turning Point’s annual convention, where Kirk welcomed them to a celebration of America. Then his mouth tightened and he got to the point.

“We’re living through a top-down revolution, everybody. We’re living through a revolution that’s different than most others. It is a cultural revolution, similar to Mao’s China. But this revolution is when the powerful, the rich, the wealthy decide to use their power and their wealth to go after you. Instead of building hospitals and improving our country, they are spending their money to destroy the greatest country ever to exist in the history of the world.”

Kirk started Turning Point in 2012, when he was 18 years old, and through tireless organizing and demagogy he built an 1,800-chapter, 600,000-student operation that brings in $80 million a year, much of it in funding from ultrarich conservatives.

“The psychology is that of civilizational suicide. The country has never lived through the wealthiest hating the country. What makes this movement different is that you are here as a grassroots response to the top-down revolution happening in this country.”

When the young leader of the grassroots counterrevolution visited college campuses to recruit for Turning Point and record himself baiting progressive students, Kirk sometimes wore a T-shirt that said THE GOVERNMENT IS LYING TO YOU, like Mario Savio and Jerry Rubin 60 years ago, demonstrating the eternal and bipartisan appeal for the young of paranoid grievance. His business model was generational outrage. He stoked anger the way Big Ag pumped groundwater.

“This is a bottom-up resistance, and it terrifies the ruling class.” Kirk was waving a finger at the students in the hall. “Will the people, who are the sovereign in this country, do everything they possibly can with this incredible blessing given to us by God to fight back and win against the elites that want to ruin it?” Elites invite 12,000 people to cross a wide-open border every day; they castrate children in the name of medicine; they try to put the opposition leader in jail for 700 years. “They hate the United States Constitution. They hate the Declaration.”

The energy rose with each grievance and insult. Kirk’s targets included Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky (“that go-go dancer”); LinkedIn’s co-founder, Reid Hoffman; Laurene Powell Jobs, the majority owner of this magazine; Senator Mitt Romney; satanists; “weak beta males” on campus; and even the Turning Pointers who had come to the convention from Mexico and Honduras (“I’m told these people are here legally”). Kirk is an accomplished speaker, and his words slide out fluidly on the grease of glib hostility and grinning mockery. But standing inside the swirl of cross-and-flag hatreds whipped up by speeches and posts and viral videos is a 6-foot-4 son of the Chicago suburbs with a smile that exposes his upper gums and the smooth face of a go-getter who made it big and married a beauty queen—as if the hatred might just be an artifice, digitally simulated.

“Elon Musk liberating Twitter will go down as one of the greatest free-speech victories in the history of Western civilization,” Kirk said. “We can say that ‘January 6 is probably an inside job; it’s more of a fed-surrection than anything else.’ And that ‘99 percent of people on January 6 did nothing wrong.’ That we can go on Twitter and say, ‘George Floyd wasn’t a hero, and Derek Chauvin was targeted in a Soviet-style trial that was anti-American and un-American.’ One of the reasons why the powerful are getting nervous is because we can finally speak again online.”

The other good news was that American high-school boys were more conservative than they’d been in 50 years—Turning Point’s mass production of memes had given a sense of purpose to a generation of males known for loneliness and suicidality. Kirk is obsessed with their testosterone levels and their emasculation by elites who “want a guy with a lisp zipping around on a Lime scooter with a fanny pack, carrying his birth control, supporting his wife’s career while he works as a supportive stay-at-home house husband. He has a playlist that is exclusively Taylor Swift. And their idea of strength is this beta male’s girlfriend opening a pickle jar just for him.”

Kirk erected an index finger.

“At Turning Point USA, we resoundingly reject this. We believe strong, alpha, godly, high‑T, high-achieving, confident, well-armed, and disruptive men are the hope, not the problem, in America.”

The picture of the American experiment grew grimmer when Kirk was followed onstage by Roseanne Barr. She was dressed all in beige, with a baseball cap and a heavy skirt pleated like the folds of a motel-room curtain, chewing something in her hollowed cheeks.

She could not make sense of her laptop and shut it. “What do you want to talk about?”

Without a speech, Barr sank into a pool of self-pity for her canceled career, which reminded her of a quote by Patrick Henry, except the words were on her laptop and all she could remember was “the summer soldier,” until her son, in the front row, handed her a phone with the quote and told her that it was by Thomas Paine.

“I’m just all in for President Trump, I just want to say that. I’m just all in … ’cause I know if I ain’t all in, they’re going to put my ass in a Gulag,” Barr said. “If we don’t stop these horrible, Communist—do you hear me? I’m asking you to hear me!” She began screaming: “STALINISTS—COMMUNISTS—WITH A HUGE HELPING OF NAZI FASCISTS THROWN IN, PLUS WANTIN’ A CALIPHATE TO REPLACE EVERY CHRISTIAN DEMOCRACY ON EARTH NOW OCCUPIED. DO YOU KNOW THAT? I JUST WANT THE TRUTH! WE DESERVE TO HEAR THE TRUTH, THAT’S WHAT WE WANT, WE WANT THE TRUTH, WE DON’T CARE WHICH PARTY IS WRONG, WE KNOW THEY’RE BOTH NOTHIN’ BUT CRAP, THEY’RE BOTH ON THE TAKE, THEY’RE BOTH STEALIN’ US BLIND. WE JUST WANT THE TRUTH ABOUT EVERYTHING THAT WE FOUGHT AND DIED AND SUFFERED TO PROTECT!”

The college boys exchanged a look and laughed. The hall grew confused and its focus began to drift, so Barr screamed louder. This was the pattern during the four days of AmericaFest, with Glenn Beck, Senator Ted Cruz, Vivek Ramaswamy, Kari Lake, Tucker Carlson, and every other far-right celebrity except Donald Trump himself: A speaker would sense boredom threatening the hall and administer a jolt of danger and defilement and the enemy within. The atmosphere recalled the politics of resentment going back decades, to the John Birch Society, Phyllis Schlafly, and Barry Goldwater. The difference at AmericaFest was that this politics has placed an entire party in thrall to a leader who was once the country’s president and may be again.

I wanted to get out of the hall, and I went looking for someone to talk with among the tables and booths. A colorful flag announced THE LIONS OF LIBERTY, and beside it sat two men who, with their round shiny heads and red 19th-century beards and immense girth, were clearly brothers: Luke and Nick Cilano, who told me they were co-pastors of a church in central Arizona. I did not yet know that the Lions of Liberty were linked to the Oath Keepers and had helped organize an operation that sent armed observers with phone cameras to monitor county drop boxes during the 2022 midterm election. But I didn’t want to talk with the Lions of Liberty about voter fraud, or border security, or trans kids, because I already knew what they would say. I wanted to talk about water.

No one at AmericaFest ever mentioned water. Discussing it would be either bad for Turning Point (possibly leading to a solution) or bad for water policy (making it another front in the culture wars). But the Cilano brothers, who live on five acres in a rural county where the aquifer is dropping, had a lot to say about it.

“The issue is, our elected officials are not protecting us from these huge corporations that are coming in that want to suck the groundwater dry,” Nick said. “That’s what the actual issue is.”

“The narrative is, we don’t have enough water,” Luke, who had the longer beard by three or four inches, added. “That’s false. The correct narrative is, we have enough water, but our elected officials are letting corporations come in and waste the water that we have.”

This wasn’t totally at odds with what experts such as Sarah Porter and Kathleen Ferris had told me. The Cilano brothers said they’d be willing to have the state come in and regulate rural groundwater, as long as the rules applied to everyone—farmers, corporations, developers, homeowners—and required solar panels and wind turbines to offset the energy used in pumping.

“This is a humanity issue,” Luke said. “This should not be a party-line issue. This should be the same on both sides. The only way that this becomes a red-blue issue is if either the red side or the blue side is legislating in their pocket more than the other.” And unfortunately, he added, on the issue of water, those legislators were mostly Republicans.

As soon as a view of common ground with the Lions of Liberty opened up, it closed again when the discussion turned to election security. After withdrawing from Operation Drop Box in response to a lawsuit by a prodemocracy group, Nick had softened his opposition to mail-in voting, but he wanted mail ballots taken away from the U.S. Postal Service in 2024 and their delivery privatized. He couldn’t get over the sense that 2020 and 2022 must have been rigged—the numbers were just too perfect.

Before depression could set in, I left the convention center and walked out into the cooling streets of a Phoenix night.

The Arizona Republican Party is more radical than any other state’s. The chief qualification for viability is an embarrassingly discredited belief in rigged elections. In December 2020, Charlie Kirk’s No. 2, Tyler Bowyer, and another figure linked to Turning Point signed on to be fake Trump electors, and on January 6, several Arizona legislators marched on the U.S. Capitol. In the spring of 2021, the state Senate hired a pro-Trump Florida firm called Cyber Ninjas to “audit” Maricopa County’s presidential ballots with a slipshod hand recount intended to show massive fraud. (Despite Republicans’ best efforts, the Ninjas increased Joe Biden’s margin of victory by 360 votes.) After helping to push Rusty Bowers out of politics, Bowyer and others orchestrated a MAGA party takeover, out-organizing and intimidating the establishment and enlisting an army of precinct-committee members to support the most extreme Republican candidates.

In 2022, the party nominated three strident election deniers for governor, attorney general, and secretary of state. After all three lost, Kari Lake repeatedly accused election officials of cheating her out of the governorship, driving Stephen Richer, the Maricopa County recorder, to sue her successfully for defamation. This past January, just before the party’s annual meeting, Lake released a secret recording she’d made of the party chair appearing to offer her a bribe to keep her from running for the U.S. Senate. When she hinted at more damaging revelations to come, the chair, Jeff DeWit, quit, admitting, “I have decided not to take the risk.” His successor was chosen at a raucous meeting where Lake was booed. Everyone involved—Lake, DeWit, the contenders to replace him, the chair he’d replaced—was a Trump loyalist, ideologically pure. The party bloodletting was the kind of purge that occurs in authoritarian regimes where people have nothing to fight over but power.

[Read: In Kari Lake, Trumpism has found its leading lady]

In April Arizona’s attorney general indicted 11 fake Trump electors from 2020, including two state senators, several leaders of the state Republican Party, and Tyler Bowyer of Turning Point, as well as Giuliani and six other Trump advisers. The current session of the legislature is awash in Republican bills to change election procedures; one would simply put the result of the state’s presidential vote in the hands of the majority party. I asked Analise Ortiz, a Democratic state representative, if she trusted the legislature’s Republican leaders to respect the will of the voters in November. She thought about it for 10 seconds. “I can’t give you a clear answer on that, and that worries me.”

Richer, the top election official in Maricopa County, is an expert on the extremism of his fellow Arizona Republicans. After taking office in 2021, he received numerous death threats—some to his face, several leading to criminal charges—and he stopped attending most party functions. Richer is up for reelection this year, and Turning Point—which is trying to raise more than $100 million to mobilize the MAGA vote in Arizona, Georgia, and Wisconsin—is coming after him.

Election denial is now “a cottage industry, so there are people who have a pecuniary interest in making sure this never really dies out,” Richer told me drily. “Some of these organizations, I’m not even sure it’s necessarily in their interest to be winning. You look at something like a Turning Point USA—I’m not sure if they want to win. They certainly have been very good at not winning. When you are defined by your grievances, as so much of the party is now and as so much of this new populist-right movement is, then it’s easier to be mad when you’ve lost.”

Richer listed several reasons MAGA is 100 proof in Arizona while its potency is weaker in states such as Georgia. One reason is the presence of Turning Point’s headquarters in Phoenix. Another is the border. “The border does weird things to people,” he said. “It contributes to the radicalization of individuals, because it impresses upon you the sense that your community is being stolen and changed.” A University of Chicago study showed that January 6 insurrectionists came disproportionately from areas undergoing rapid change in racial demographics. And, Richer reminded me, Phoenix “contributed the mascot.”

Jacob Chansley, the QAnon Shaman, sat waiting at a table outside a Chipotle in a northwest-Phoenix shopping mall. He was wearing a black T-shirt, workout shorts, and a ski hat roughly embroidered with an American flag. Perhaps it was the banal setting, but even with his goat’s beard and tattoos from biceps to fingernails, he was unrecognizable as the horned and furred invader of the Capitol. For a second, he disappeared into that chasm between the on-screen performance and the ordinary reality of American life.

The Shaman was running as a Libertarian in Arizona’s red Eighth Congressional District for an open seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. “Can you imagine the kind of statement it would send to the uniparty in D.C. to send me back as a congressman?” Chansley wouldn’t be able to vote for himself—he was still on probation after serving more than two years in a federal prison. It was hard to tell to what extent his campaign actually existed. He was accepting no money from anyone, and when I asked how many signatures he’d collected for a petition to get on the ballot, he answered earnestly, “Over a dozen.” (He would ultimately fail to submit any at all.) That was how Chansley talked: with no irony about circumstances that others might find absurd. There was an insistent strain in his voice, as if he had spent his life trying to convince others of something urgent that he alone knew, with a stilted diction—“politics and the government and the legislation therein has been used to forward, shall we say, a less than spiritual agenda”—that seemed familiar to me.

Why was he running for Congress? Unsurprisingly, because politicians of the uniparty were all in the pocket of special interests and international banks and did not represent the American people. His platform consisted of making lobbying a crime, instituting term limits for congresspeople and their staff, and prosecuting members engaged in insider trading. Meanwhile, Chansley was supporting himself by selling merch on his website, ForbiddenTruthAcademy.com, and doing shamanic consultations.

Why had he gone to the Capitol in regalia on January 6? He had a spiritual answer and a political answer. The Earth’s electromagnetic field produces ley lines, he explained, which crisscross one another at sacred sites of civilizational importance, such as temples, pyramids, and the buildings on the National Mall. “If there’s going to be a million people assembling on the ley lines in Washington, D.C., it’s my shamanic duty, I believe, to be there and to ensure that the highest possible frequencies of love and peace and harmony are plugged into the ley lines.” That was the spiritual answer.

The political answer consisted of a long string of government abuses and cover-ups going back to the Tuskegee experiment, and continuing through the Warren Commission, Waco, Oklahoma City, 9/11, Iraq, Afghanistan, Hillary Clinton’s emails, COVID and the lockdowns, Hunter Biden’s laptop, and finally the stolen 2020 election. “All of these things were like a culmination for me,” he said, “ ’cause I have done my research, and I looked into the history. I know my history.” Chansley’s only regret about January 6 was not anticipating violence. “I would have created an environment that was one of prayer and peace and calm and patience before anything else took place.” That day, he was at the front of the mob that stormed the Capitol and broke into the Senate chamber, where he left a note on Vice President Mike Pence’s desk that said, “It’s only a matter of time, justice is coming.”

As for the conspiracy theory about a global child-sex-trafficking ring involving high-level Democrats: “Q was a successful psychological operation that disseminated the truth about corruption in our government.”

One leader had the Shaman’s complete respect—Donald Trump, who sneered at globalists and their tyrannical organizations, and who, Chansley said with that strain of confident knowing in his voice, declassified three vital patents: “a zero-point-energy engine, infinite free clean energy; a room-temperature superconductor that allows a zero-point-energy engine to function without overheating; and what’s called a TR3B—it’s a triangular-shaped antigravity or inertia-propulsion craft. And when you combine all these things together, you get a whole new socioeconomic-geopolitical system.”

When the Shaman got up to leave, I noticed that he walked slew-footed, sneakers turned outward, which surprised me because he was extremely fit, and I suddenly thought of a boy in my high school who made up for awkward unpopularity by using complex terms to explain forbidden truths that he alone knew and everyone else was too blind to see. Chansley was a teenage type. It took a national breakdown for him to become the world-famous symbol of an insurrection, spend two years in prison, and run for Congress.

5. The Aspirationalist

“Can the American experiment succeed? It’s not ‘can’—it has to. That doesn’t mean it will.”

Michael Crow, the president of Arizona State University, wore two watches and spoke quickly and unemotionally under arched eyebrows without smiling much. He was physically unimposing at 68, dressed in a gray blazer and blue shirt—so it was the steady stream of his words and confidence in his ideas that suggested why several people described him to me as the most powerful person in Arizona.

“I am definitely not a declinist. I’m an aspirationalist. That’s why we call this the ‘new American university.’ ”

If you talk with Crow for 40 minutes, you’ll probably hear the word innovative half a dozen times. For example, the “new American university”—he left Columbia University in 2002 to build it in wide-open Phoenix—is “highly entrepreneurial, highly adaptive, high-speed, technologically innovative.” Around the Valley, Arizona State has four campuses and seven “innovation zones,” with 145,000 students, almost half online; 25,000 Starbucks employees attend a free program to earn a degree that most of them started somewhere else but never finished. The college has seven STEM majors for every one in the humanities, graduating thousands of engineers every year for the Valley’s new tech economy. It’s the first university to form a partnership with OpenAI, spreading the free use of chatbots into every corner of instruction, including English. Last year, the law school invited applicants to use AI to help write their essays.

Under Crow, Arizona State has become the kind of school where faculty members are encouraged to spin off their own companies. In 2015, a young materials-science professor named Cody Friesen founded one called Source, which manufactures hydropanels that use sunlight to pull pure drinking water from the air’s moisture, with potential benefits for the world’s 2.2 billion people who lack ready access to safe water, including those on the Navajo reservation in Arizona. “If we could do for water what solar did for electricity, you could then think about water not as a resource underground or on the surface, but as a resource you can find anywhere,” Friesen told me at the company’s headquarters in the Scottsdale innovation zone.

But the snake of technology swallows its own tail. Companies such as Intel that have made the Valley one of the largest job-producing regions in the country are developing technologies that will eventually put countless people, including engineers, out of work. Artificial intelligence can make water systems more efficient, but the data centers that power it, such as the new one Microsoft is building west of Phoenix in Goodyear, have to be cooled with enormous quantities of water. Arizona State’s sheer volume and speed of growth can make the “new American university” seem like the Amazon of higher education. Innovation alone is not enough to save the American experiment.

[Read: AI is taking water from the desert]

For Crow, new technology in higher education serves an older end. On his desk, he keeps a copy of the 1950 course catalog for UCLA. Back then, top public universities like UCLA had an egalitarian mission, admitting any California student with a B average or better. Today they compete to resemble elite private schools—instead of growing with the population, they’ve become more selective. Exclusivity increases their perceived value as well as their actual cost, and it worsens the heart-straining scramble of parents and children for a foothold in the higher strata of a grossly unequal society. “We’ve built an elitist model,” Crow said, “a model built on exclusion as the measurement of success, and it’s very, very destructive.”

This model creates the false idea that certain credentials are the only proof of a young person’s worth, when plenty of capable students can’t get into the top schools or don’t bother trying. “I’m saying, if you keep doing this—everyone has to be either Michigan or Berkeley, or Harvard or Stanford, or you’re worthless—that’s gonna wreck us. That’s gonna wreck the country,” Crow said, like a Mad Max film whose warring gangs are divided by political party and college degree. “I can’t get some of my friends to see that we, the academy, are fueling it—our sanctimony, our know-it-all-ism, our ‘we’re smarter than you, we’re better than you, we’re gonna help you.’ ”

The windows of his office in Tempe look out across the street at a block of granite inscribed with the words of a charter he wrote: “ASU is a comprehensive public research university, measured not by whom it excludes, but by whom it includes and how they succeed.” Arizona State admits almost every applicant with at least a B average, which is why it’s so large; what allows the university to educate them all is technology. Elite universities “don’t scale,” Crow said. “They’re valuable, but not central to the United States’ success. Central to the United States’ success is broader access to educational outcomes.”

The same windows have a view of the old clay-colored Tempe Normal School, on whose steps Theodore Roosevelt once foresaw 100,000 people living here. Today the two most important institutions in the Valley are the Salt River Project and Arizona State. Both are public enterprises, peculiarly western in their openness to the future. The first makes it possible for large numbers of people to live here. The second is trying to make it possible for them to live together in a democracy.

In 2016, the Republican majority in the Arizona legislature insisted on giving the university $3 million to start a School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership. SCETL absorbed two earlier “freedom schools” dedicated to libertarian economics and funded in part by the Charles Koch Foundation. The new school is one innovation at Arizona State that looks backwards—to the founding principles and documents of the republic, and the classical philosophers who influenced them. Republican legislators believed they were buying a conservative counterweight to progressive campus ideology. Faculty members resisted this partisan intrusion on academic independence, and one left Arizona State in protest. But Crow was happy to take the state’s money, and he hired a political-science professor from the Air Force Academy named Paul Carrese to lead the school. Carrese described himself to me as “an intellectual conservative, not a movement conservative,” meaning “America is a good thing—and now let’s argue about it.”

I approached SCETL with some wariness. Koch-funded libertarian economics don’t inspire my trust, and I wondered if this successor program was a high-minded vehicle for right-wing indoctrination on campus, which is just as anti-intellectual as the social-justice orthodoxy that prevails at elite colleges. Yet civic education and civic virtue are essential things for an embattled democracy, and generally missing in ours. So is studying the classics of American history and thought in a setting that doesn’t reduce them to instruments of present-day politics.

As we entered the campus building that houses SCETL, a student stopped Carrese to tell him that she’d received a summer internship with a climate-change-skeptical organization in Washington. On the hallway walls I saw what you would be unlikely to see in most academic departments: American flags. But Carrese, who stepped down recently, hired a faculty of diverse backgrounds and took care to invite speakers of opposing views. In a class on great debates in American political history, students of many ethnicities, several nationalities, and no obvious ideologies parsed the shifting views of Frederick Douglass on whether the Constitution supported slavery.

Crow has defended SCETL from attempts by legislators on the right to control it and on the left to end it. Republican legislatures in half a dozen other states are bringing the model to their flagship universities, but Carrese worries that those universities will fail to insulate the programs from politics and end up with partisan academic ghettos. SCETL’s goal, he said, is to train students for democratic citizenship and leadership—to make disagreement possible without hatred.

“The most committed students, left and right, are activists, and the center disappears,” Carrese said. This was another purpose of SCETL: to check the relentless push toward extremes. “If students don’t see conservative ideas in classes, they will go off toward Charlie Kirk and buy the line that ‘the enemy is so lopsided, we must be in their face and own the libs.’ ”

Turning Point has a large presence at Arizona State. Last October, two Turning Point employees went on campus to get in the face of a queer writing instructor as he left class in a skirt, pursuing and filming him, and hectoring him with questions about pedophilia, until the encounter ended with the instructor on the ground bleeding from the face and the Maricopa County attorney filing assault and harassment charges against the two Turning Point employees. “Cowards,” Crow said in a statement. He had previously defended Kirk’s right to speak on campus, but this incident had nothing to do with free speech.

Leading an experiment in mass higher education for working- and middle-class students allows Crow to spend much less time than his Ivy League counterparts on speaker controversies, congressional investigations, and Middle East wars. The hothouse atmosphere of America’s elite colleges, the obsessive desire and scorn they evoke, feels remote from the Valley. During campus protests in the spring, Arizona State suspended 20 students—0.0137 percent of its total enrollment.

6. The Things They Carried

Two hours before sunrise, Fernando Quiroz stood in the bed of his mud-caked truck in a corner of Arizona. Eighty people gathered around him in the circle of illumination from a light tower while stray dogs hunted for scraps. It was February and very cold, and the people—men with backpacks, women carrying babies, a few older children—wore hooded sweatshirts and coats and blankets. Other than two men from India, they all came from Latin America, and Quiroz was telling them in Spanish that Border Patrol would arrive in the next few hours.

“You will be asked why you are applying for asylum,” he said. “It could be violence, torture, communism.”

They had been waiting here all night, after traveling for days or weeks and walking the last miles across the flat expanse of scrubland in the darkness off to the west. This was the dried-up Colorado River, and here and there on the far side, the lights of Mexico glimmered. The night before, the people had crossed the border somewhere in the middle of the riverbed, and now they were standing at the foot of the border wall. They were in America, but the wall still blocked the way, concealing fields of winter lettuce and broccoli, making sharp turns at Gate 6W and Gate 7W and the canal that carried Mexico’s allocated Colorado River water from upstream. Quiroz’s truck was parked at a corner of the wall. Its rust-colored steel slats rose 30 feet overhead.

Seen from a distance, rolling endlessly up and down every contour of the desert, the wall seemed thin and temporary, like a wildly ambitious art installation. But up close and at night it was an immense and ominous thing, dwarfing the people huddled around the truck.

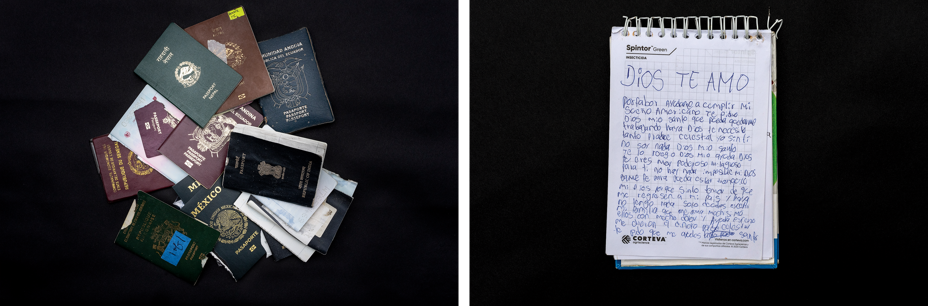

“Put on your best clothes,” Quiroz told them. “Wear whatever clothes you want to keep, because they’ll take away the rest.” They should make their phone calls now, because they wouldn’t be able to once Border Patrol arrived. They would be given a gallon-size ziplock bag and allowed into America with only what would fit inside: documents, phones, bank cards. For all the other possessions that they’d chosen out of everything they owned to carry with them from all over the world to the wall—extra clothes, rugs, religious objects, family pictures—Border Patrol would give them a baggage-check tag marked Department of Homeland Security. They would have 30 days to come back and claim their belongings, but hardly anyone ever did—they would be long gone to Ohio or Florida or New York.

At the moment, most of them had no idea where they were. “This is Arizona,” Quiroz said.

As he handed out bottled water and snacks from the back of his truck, a Cuban woman asked, “Can I take my makeup?”

“No, they’d throw it out.”

A woman from Peru, who said she was fleeing child-kidnappers, asked about extra diapers.

“No, Border Patrol will give you that in Yuma.”

I watched the migrants prepare to abandon what they had brought. No one spoke much, and they kept their voices low. A man gave Quiroz his second pair of shoes in case someone else needed them. A teenage girl named Alejandra, who had traveled alone from Guatemala, held a teddy bear she’d bought at a Mexican gas station with five pesos from a truck driver who’d given her a ride. She would leave the teddy bear behind and keep her hyperthyroid medicine. Beneath the wall, a group of men warmed themselves by the fire of a burning pink backpack. In the firelight, their faces were tired and watchful, like the faces of soldiers in a frontline bivouac. A small dumpster began to fill up.

For several years, Quiroz had been waking up every night of the week and driving in darkness from his home in Yuma to supply the three relief stations he had set up at the wall and advise new arrivals, before going to his volunteer job as a high-school wrestling coach. He had the short, wiry stature and energy of a bantamweight, with a military haircut and midlife orthodontia installed cheap across the border. He was the 13th child of Mexican farmworkers, the first to go to college, and when he looked into the eyes of the migrants he saw his mother picking lettuce outside his schoolroom window and asked himself, “If not me, then who?”

He was volunteering at the deadliest border in the world. A few miles north, the wall ended near the boundary of the Cocopah reservation, giving way to what’s known as the “Normandy wall”—a long chain of steel X’s that looked like anti-craft obstacles on Omaha Beach. Two winters ago, checking his relief station there, Quiroz found an old man frozen to death. Last summer, a woman carrying a small child crossed the canal on a footbridge and turned left at the wall instead of going right toward Gates 6W and 7W. She walked a few hundred yards and then sat down by the wall and died in the heat. (The child survived.) Afterward, Quiroz put up a sign pointing to the right.