The Blindness of Elites

No one really knows what America looks like anymore. Walter Kirn wants to change that.

one afternoon in the mid-1980s, while on scholarship at the University of Oxford, Walter Kirn came upon a bulletin announcing that Jorge Luis Borges was visiting the campus and wished to meet students informally. Kirn, the future writer and critic, then in his early 20s and a recent Princeton graduate, glanced at his watch and realized that the event started in 10 minutes.

He hurried down to one of those little rooms where Oxford students drank sherry with their dons. Borges, bent over an old-fashioned cane, leaning on a nurse’s arm, with wraparound sunglasses to shield his blind eyes, walked in. To Kirn, Borges had until then existed wholly outside space and time, less a human being than a synonym for capital-L Literature, like Kafka or Cervantes. Now the famous writer offered the cowed students an icebreaker. “I have a game I like to play,” he said. “I like to edit, or revise, Shakespeare.” On long flights or when he was bored, he would take Shakespeare’s speeches and try to improve them. He gave an example of a line he’d adjusted from King Lear. “Isn’t it plainly much better?” Borges asked.

Whether it was better was not what interested Kirn. Borges was revising “some of the greatest pieces of oratory in the English language,” Kirn recently told me. He was still, 40 years later, amazed. The lesson he drew was that no authority was beyond question.

Kirn went on to write for a long list of newspapers and magazines (including this one). He married and divorced the daughter of a famous actress. He wrote the novel Up in the Air, which was turned into a movie starring George Clooney (who, Kirn says, tried to swoop in on his own girlfriend—the writer Amanda Fortini—when she visited the set; Fortini is now his wife). In his hilarious 2009 memoir, Lost in the Meritocracy (which began as an Atlantic cover story), he described how he came to be a member of “the class that runs things,” the one that “writes the headlines, and the stories under them.” It was the account of a middle-class kid from Minnesota trying desperately to fit into the elite world—and then realizing that he didn’t want to fit in at all. Now 61, Kirn has a newsletter on Substack, co-hosts a lively podcast devoted in large part to critiquing establishment liberalism, writes the kind of provocative tweets that not everyone understands are jokes (in part because some aren’t), and appears on Fox’s late-night comedy show. Depending on one’s perspective, he is either a spokesperson for a forgotten America, a truth teller in a grim and timid time, or a recklessly contrarian apologist for Donald Trump and the more conspiratorially minded of his supporters.

[From the January/February 2005 issue: Lost in the meritocracy]

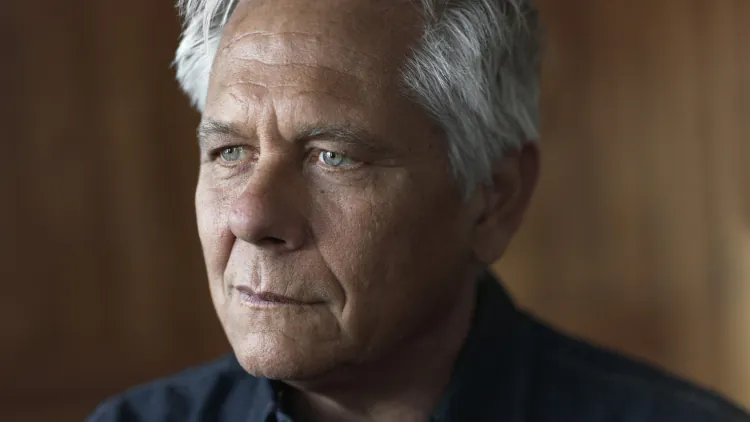

In March, I spent two days with him in Livingston, Montana, where he moved from New York City more than 30 years ago. Bronze-skinned even in winter, Kirn has thick white hair and a prankster’s smile. When he speaks, he’ll glance around the room and drop his voice before reestablishing eye contact, so you feel as though he’s letting you in on a secret. Then he tells you a story: the one about how he flipped his car into a creek while not wearing a seat belt; or how he ended up euthanizing his mother, who was comatose and dying of a brain infection; or when he drove his truck over his baby, who had crawled into the driveway and emerged from between the wheels miraculously unscathed.

Even many of his sharpest political arguments take the shape of a yarn. Kirn’s father died in May 2020, but Kirn still maintains his house in Livingston; on a visit there he showed me, hanging in the garage, an American flag with a superimposed black-and-white photograph of a rifle-toting Geronimo. Kirn calls Geronimo an American hero for asserting his own inherent dignity and refusing to make peace with the United States. Geronimo was eventually imprisoned at Fort Sill in Oklahoma, until he died and was buried there. Then, in 1918, Kirn says, “fucking Prescott Bush comes in and fucking steals his skull. You know where his skull is? Skull and Bones. It’s their fucking little totem for their Yale secret society! They took his fucking skull, and it sits there.”

The story might be apocryphal (there’s no hard evidence that Geronimo’s grave was looted, though some historians consider it plausible). But it captures something essential about Kirn, who can seem, like Trump himself, less concerned with the strict facticity of the claims he makes than with the sins of the people he’s attacking.

Kirn would never describe himself as a Trump supporter, but he cares less about Trump’s rampage through American democracy, or even the lunacy and violence of January 6, than he does about the selfish and self-satisfied elites—all noblesse, no oblige—who sparked that anger and sustained it. Call him a counter-elite. As he said about Skull and Bones: “That’s our elite. Who wouldn’t want to be counter to it?”

Kirn described the dominant politics of his Minnesota youth as “rural progressivism.” He spoke reverently of his grandfather, also named Walter Kirn, a local politician in Akron, Ohio, who, in the 1950s, ruined his career by defending the right of the Black thespian and suspected communist Paul Robeson to come to town. Family legend has it that he opened up a high-school auditorium for Robeson’s performance “purely on the basis of his right to express himself. It wasn’t out of empathy for his views.” Kirn sees that “as the right kind of politics.”

Today he regards Trump’s supporters not as the proverbial basket of deplorables but as more or less reasonable citizens with valid concerns. The movement around Trump, Kirn told me, is “an expression of American frustration on the part of people who feel like they got a really raw deal.” He described himself as “anti-anti-Trump, in the sense that I don’t think that this is the unique challenge in American history for which we should throw away all sorts of liberties and prerogatives that we are going to want back.” One reason he doesn’t see the coming election as a state of emergency is he does not believe that previous American leaders, such as the Bushes, were particularly virtuous, even in comparison with Trump—a figure Kirn and his colleagues at that bastion of 1990s East Coast snobbism, Spy magazine, used to relentlessly mock. Here, Kirn’s personal evolution is telling: He is perhaps the most salient example of a mainstream writer rejecting his past to throw in with the populists.

Kirn is right that, as the internet and social media have allowed us to peer inside our national institutions, there is no denying their stewards have suffered profoundly from the exposure. And yet, I kept asking myself a question and phrasing it to Kirn in different ways: Why can’t we do two things simultaneously? Why can’t we revise our estimation of a decadent and often deceitful ruling class and refuse to downplay the sui generis outrage that is Donald Trump? It is not an acquittal of George W. Bush’s grandfather to insist that a second Trump term would be a mistake.

Whenever I tried this tack with Kirn, he didn’t dispute it. It just wasn’t an argument that excited him.

Kirn first came to Livingston to report on the Church Universal and Triumphant, an eschatological cult of about 2,000 members that built bomb shelters in preparation for Armageddon. “People were charging up their credit cards because they thought the bills would never come due,” he later wrote in a story about the movement for Slate. “They were buying ammunition by the crate load.” Kirn had flown out west to witness the end of the world and liked it so much that he stayed.

Kirn’s own ex-father-in-law, the writer Thomas McGuane, coined the term flyover country. Kirn was drawn to the freedom and openness of the land, and on the drive from the airport, the jagged Rockies brushed orange by the sunset, I could easily see why. Livingston had once been a thriving railroad town, as well as the gateway to Yellowstone, America’s first national park. But by the time Kirn showed up, the Northern Pacific Railroad had shuttered its Italianate depot, and he could purchase an entire building with the money he made writing book reviews. The area was majestic; Tom Brokaw owned (and still owns) a sprawling ranch nearby. There weren’t even speed limits on the highways. And so, as he once put it, he became “a resident of Montana’s center (both geographically and politically).”

Not everyone would describe Kirn as a centrist now, certainly not since the election of 2016.

Reporting for Harper’s on the Republican convention, Kirn was immediately attuned to Trump’s appeal. He also saw an opportunity to showcase his own growing estrangement from mainstream liberal journalism:

The media loungers with their gift for telepathic quasi plagiarism have reached their verdict, and many of them pronounce it in the same words. Dark. Dystopian. Negative. A turnoff. My pal in California, the conspiratorial libertarian who’ll probably write in Frank Zappa on his ballot, would likely say, “I guess they got the memo.” But I didn’t see the memo. I’ve never seen the memo, maybe because I don’t work for the large outfits. I’m not a joiner.

Today, Kirn believes that the coverage of Trump’s presidency—followed by the public-health messaging and regulations during the pandemic—poses a much more significant threat than Trump to American democracy. He’s just “not that astonishing an American character,” Kirn told me. “America tries all kinds of types. It tries the pseudo-aristocrat”—John F. Kennedy. It tries “the smoothie”—Barack Obama and Bill Clinton. It tries “the adultish son, like George Bush.” Trump is “the rough salesman” archetype.

The pandemic accelerated Kirn’s contrarian drift, or at least made him more vocal about his distrust of elite institutions. On X, he can evince a conspiracy-sympathetic persona, directing fury at an abstract, sometimes straw-manned establishment. “For years now, the answer, in every situation—‘Russiagate,’ COVID, Ukraine—has been more censorship, more silencing, more division, more scapegoating. It’s almost as if these are goals in themselves & the cascade of emergencies excuses for them. Hate is always the way,” he wrote in 2022. “The authorities and the incurious corporate press are belatedly acknowledging the truth about COVID so they can repair their reputations sufficiently to lie to us about new things,” he posted in 2023. Early in the pandemic, Kirn’s father was dying of Lou Gehrig’s disease in Arizona, and Kirn defied multiple quarantine requirements to bring him in an RV to Montana so that he could tend to him. For Kirn, the heavy-handed restrictions were not just ill-advised. They were a pernicious assault on freedom that felt deeply personal.

But Kirn insists that he’s stayed the same—that his ideological trajectory is actually defined by relative stasis. When I asked the journalist Matt Taibbi, Kirn’s friend and podcast partner on America This Week, how he would describe Kirn’s politics, he told me Kirn was an “old-school liberal,” reiterating that it was the other so-called liberals who had changed. “I’ve been told repeatedly in the last year that free speech is a right-wing issue,” Taibbi (another man of the left whom some view as having drifted rightward) said. “I wouldn’t call him conservative. I would just say he’s a free thinker, nonconformist, iconoclastic.”

“I’m not quite a libertarian,” Kirn told me, as we whipped his John Deere Gator across the knee-deep Montana snow. The occasional melted patch splattered us with mud. “I believe we should organize to do all sorts of things for the common good.” He said he resented being coded conservative: “I was like, Dude, you guys are jumping off the ship. I’m staying on the ship. This is the same ship I’ve been on.”

The first time I saw Walter Kirn in person, he seemed overcome by anger and hostility. Last fall, we both participated in a conference celebrating the pioneering theorist René Girard at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C. Kirn’s panel, “Free Speech, Censorship, and the New Media,” was the liveliest of the day and went sideways almost immediately. Kirn launched, seemingly out of nowhere, into a tirade, at one point heaping scorn on a fellow panelist, Renée DiResta, an expert on propaganda at the Stanford Internet Observatory. (DiResta is also a frequent contributor to The Atlantic.) He suggested that her group was connected to defense and intelligence agencies, calling it “the only observatory I know that has offensive capabilities to shoot down stars and planets.”

He repeatedly compared the media to the Empire in The Empire Strikes Back. He asserted that news organizations like The New York Times and CBS News were serving “the corporate and state interests that don’t believe you are wanting the right things—you might want Donald Trump—or that you aren’t wanting the things you should want enough—the COVID vaccine.” The media dismissed, he said, stories about “countries having problems with the COVID vaccine” as “malinformation.” (He did not provide examples.) This revealed that the government’s attempts to manage the pandemic were a “behavioral-engineering enterprise, no longer having much to do with the truth, no longer having much to do with your right to desire what you wish or not desire what you don’t wish.”

Everyone, he suggested, was in on the game. “This group of legacy media institutions, along with a whole array of academic—what is called ‘civil-society organizations’—and frankly, Homeland Security, clerks of the government, got together and … ganged up to preserve this preferential cartel status for those groups and start shooting down the rebel ships.”

Kirn appeared genuinely livid; the panelists—and the audience—seemed baffled.

One of Girard’s famous theories is called the “scapegoat mechanism.” Communities keep violence from rupturing them apart, he argued, by projecting their internal tensions onto an arbitrarily chosen individual. A startled-looking DiResta was referencing this when she broke in at one point to say she thought Kirn was “scapegoating, actually.” He said he couldn’t possibly scapegoat someone so powerful: “Little Walter Kirn to scapegoat Stanford University, Congress, and the State Department … places that take money from the Defense Department and Homeland Security?”

“I don’t take money from either,” DiResta objected.

That evening, Kirn and I were seated together at dinner, just a table away from one of the most controversial elites in America, the billionaire libertarian Peter Thiel. Kirn seemed not just unbothered by this but in terrific spirits—a mood I found hard to reconcile with the ferocity of his encounter with DiResta.

[Read: Peter Thiel is taking a break from democracy]

DiResta later told me that Kirn had privately apologized after the panel for, in her words, “turning me into a caricature.” Kirn told me that he doesn’t remember apologizing, but that the two of them spoke at length and “what drove the conversation for me was the desire to be cordial after a heated debate” and “to better understand her position.” I asked DiResta if there was any truth to the charge that she was working for the Defense Department or other agencies. She responded that she’d interned at the CIA as an undergraduate, but “the claim that my internship 20 years ago and my current work are in any way connected is bullshit.” She told me that the Stanford Internet Observatory had received a government grant in the past—from the National Science Foundation—but that “neither our 2020-election work” nor studies her organization published on vaccine rumors “were government-funded.”

When I probed Kirn about these kinds of conspiratorial claims in our conversations over the past few months, he didn’t try to smooth them over. “I didn’t feel I was attacking her personally,” he said. “She didn’t come as an individual; she came as a résumé representing a field.” Then he reiterated his original position. “Bottom line is, I stand by what I said … But if some fact-check proves I got something wrong, then I did.”

This last point seems emblematic of much larger difficulties in our national discourse as it becomes ever more fractured and cynical. There is really nothing DiResta can say to satisfactorily dispel the conspiracy, because it is impossible to prove a negative. And besides, if she were a government plant, she certainly wouldn’t tell me that. And so we are forever stuck in the purgatory of innuendo.

“I believe in ferment,” Kirn told me in Livingston. “I believe that we should have a society in which the bubbles rise up and explode with little new thoughts.” The point seemed to be that an exaggerated criticism, even one that is performative or liable to miss its mark entirely, would always be preferable to deferential silence. Freedom alone is of the utmost importance: “Not just freedom in the sense of like, ‘I’m going to shoot my gun.’ But freedom in not having to repeat stale bromides, not having to please power with their production.”

The fact of this defiant posture, Kirn suggests, is the real and lasting message. Such a line of thinking can be persuasive. “Sometimes paranoia just stands to reason,” Kirn argued in The New York Times after the very real enigma of the death of Jeffrey Epstein. Or, as he put it more bluntly on Twitter, “My only problem with ‘conspiracy theories’ is that they don’t go far enough.” Yet once you begin to punch at everything, you’re bound to strike the wrong target sometimes.

I had not quite known what to make of Kirn after that panel in Washington. What became clear to me in Montana is that his resentment against the tastemakers and gatekeepers is so unrelenting because it’s fueled not simply by dislike but also by real affection—a sympathy for Americans in unimportant places, people without power or influence, whose opinions and lifestyles he believes are often dismissed as retrograde or irrelevant.

On this point, I felt myself indicted. Though certainly not born into it, I have come to be ensconced within a privileged coastal “knowledge” class that, in my opinion, too often sees the rest of the country as either inscrutable or irredeemable. And so I found Kirn, the charismatic class traitor, a far more effective ventriloquist for working-class frustrations than the former, and possibly future, president.

Earlier in his career, Kirn was sent to places like Livingston to write what he sees now as voyeuristic stories about the locals, the purpose of which was “to execute on all the prejudices that were behind the assignment.” GQ once flew him to Colorado to file a portrait of young men who reenact Vietnam War battles. He learned that all the men had poignant stories. “I wrote an incredibly sympathetic piece. It was not what [the editors] expected. It was not what they wanted. I was finally like, ‘I’m not going to be a fucking hit man for Madison Avenue,’ for Condé Nast, that goes out and finds quirky Americans and makes fun of them so we can have Absolut Vodka on the next page—yeah, Absolut—and, like, a report from Milan Fashion Week … I was just like, ‘This sucks.’”

GQ never ran the story, but Kirn resolved to keep writing about people he believed institutions like Condé Nast ignored. In 2018, he spent two and a half months driving across the country for a book that he said should come out next year called The Last Road Trip. He said he found a variety of Americans from many races who just feel screwed: “I’m fucked. My neighborhood’s fucked; my town’s fucked. My region is fucked.”

He described passing through “coal country”: “It’s so polluted down there, and they’re hanging on, and these are the people that everybody else hates. Everybody can agree, no matter where they’re from, that rednecks are the worst fucking people in America.”

“We’re talking a big game about justice and advancement and the future and multicultural tolerance and so on,” he expanded. “Meanwhile, vast cities are just turning into fucking toxic Superfund sites, socially and chemically … and we’re just saying those people couldn’t adjust or those places aren’t important.

“All we’re doing,” he continued, “is closing up rooms in the house that we can no longer heat.”

Last year, Kirn began publishing a print-only broadsheet, along with the writer David Samuels, called County Highway, which bills itself playfully as “America’s Only Newspaper.” Its purpose is to treat the rest of the country with the interest that is directed at New York City and San Francisco. It’s a quixotic publication—with six issues a year and, Samuels told me, a print run of 22,500 copies. “Most of those copies sell,” he said. “The remainder goes to us, to contributors, and to our friends, who use them to make paper boats and funny hats.” They’ve run articles on euthanasia laws in Canada, professional wrestling in Puerto Rico, and “the best little Basque restaurant in Elko, Nevada.” The fact that County Highway is most likely to be found in record shops and cute general stores, and on the type of newsstands that stock The Paris Review and foreign editions of Vogue, might make you wonder how populist it can really be. (Samuels—a New Yorker with degrees from Harvard and Princeton—wrote for many years for The New York Times Magazine, among other places.)

I asked Kirn: Is founding what is essentially a literary magazine really an effective way to strike a blow against American elitism?

He told me that “American prose literature—the literature of Mark Twain, Willa Cather, Ralph Ellison, Jack Kerouac—has to be the least ‘elitist’ major cultural product in world history.” He sees County Highway as “firmly in that tradition, neither concerned with the high or the low, but only with the abiding American voice.” I don’t know that the effort can produce a contemporary Cather or Twain—let alone if non-elites would even care for such a thing. But the ethics of the gesture, its desire to expand the journalistic zone of interest, is serious, a defining characteristic of Kirn’s life project. What he’s against, he told me, is “blindness.”

On a fundamental level, Kirn is right. This America that he wishes to dwell upon—and force us to acknowledge—is not what most of us who are invested with access or influence care to deal with. We may say the right things, but our notions of diversity, inclusivity, and justice are extremely narrowly defined. And as the polls keep showing in the run-up to November’s election, Kirn is correct to point out that a growing multiethnic assortment of citizens find themselves more repelled by the status quo than they are by Trump’s return.

Kirn is under no delusions that, even as he positions himself as a contrarian, he remains wholly within the group he is critiquing. There is something compelling about a man who has gone to all the right schools and worked for all the right places and made a smashing success of himself who then turns and spits on all of it, insisting that it was never worth a damn to begin with.

But even as I found myself swept up by his oratory about elite indifference, I knew he was at times overstating the case—fixating on just a part of the larger story. (It’s the same temptation the most stringent voices on the left give in to when they dismiss the history of Enlightenment values in American democracy to focus solely on white supremacy.) Of course, The New York Times has published reams of investigative reporting on the opioid crisis and suburban and rural squalor. Of course, elites have made attempts—even if sometimes cringe-inducing—to understand the politics of the working class and its consequential sense of betrayal. And, of course, it should be entirely possible to listen to the voices of struggling Americans, wherever we might find them, and still want more for them—and for us—than Donald Trump and his nihilistic rebellion.

I left Montana certain that we need provocative contrarians like Walter Kirn, who are stubborn and capable enough to see through and question the powerful. We also need to remember the wisdom of Borges: No one is infallible. And so the counter-elites, too, must be questioned.

What's Your Reaction?