You Think You’re So Heterodox

Joe Rogan has turned Austin into a haven for manosphere influencers, just-asking-questions tech bros, and other “free thinkers” who happen to all think alike.

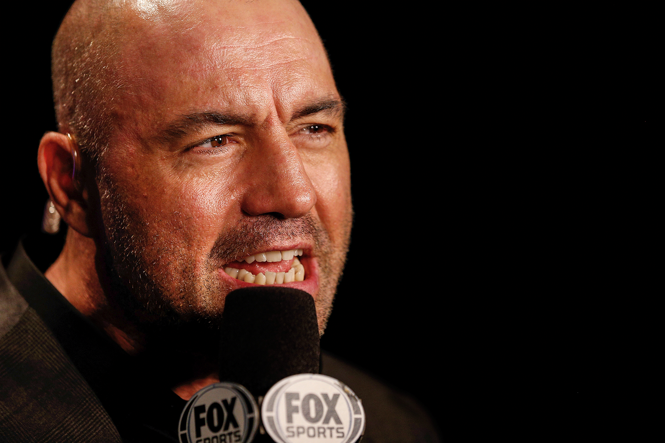

It’s a Tuesday night in downtown Austin, and Joe Rogan is pretending to jerk off right in front of my face. The strangest thing about this situation is that millions of straight American men would kill to switch places with me.

Centimillionaires generally pride themselves on their inaccessibility, but most weeks you can see Rogan live at the Comedy Mothership, which he owns, in exchange for $50 and a two-drink minimum. About 250 tickets for each “Joe Rogan and Friends” show go on sale every Sunday at 2 p.m. central time, and disappear within seconds. When you arrive at the Mothership, the staff locks your phone in a bag, which both ensures that you cannot leak footage online and makes you think you’re about to see some really forbidden shit.

You are not. What you will see is four comedians, plus Rogan himself, with routines that might shock the Amish, the over-80 set, college students, Vox staffers, or John Oliver superfans—but not anyone who, say, went to a comedy club in the 1990s. Of the many recent failures of the American left, one of the greatest is making entry-level battle-of-the-sexes humor seem avant-garde. (Did you know that women often run relationship decisions past their female friends? Bitches be crazy! That sort of thing.) As Rogan himself says after he emerges in stonewashed jeans, clutching a glass of something amber on ice: “Fox News called this an anti-woke comedy club. That’s just a comedy club!” To underline the point that these jokes can survive outside the safe space of the Mothership, much of the material I saw Rogan perform ended up in his latest Netflix special, which was released in August.

[Read: Why is Joe Rogan so popular?]

In Austin, the masturbation mimicry happens during a riff about concealing his porn consumption from his wife—“the best person I know,” he says, sweetly. That routine captures the essence of the Joe Rogan brand: He is bawdy around his fans, respectful of his wife, loyal to his friends, and indulgent with his golden retriever, who has 900,000 followers on Instagram. He maintains a self-deprecating sense of humor that’s rare among men who could buy an island if they wanted one. His politics defy easy categorization—he hates Democratic finger-wagging but supports gay marriage and abortion rights. (“I’m so far away from being a Republican,” he said on a podcast in 2022.) He voted for a third-party candidate in 2020, and in early August expressed his admiration for Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a former guest on The Joe Rogan Experience. He also wonders if President Biden might have been replaced by a body double. (Does he have any evidence? Sure, the guy looks taller now.) He sees himself as an outsider, nontribal, just an average Joe. The best way to think of him, one of my friends told me, is as if “Homer Simpson got swole.”

Another way to think of him: as perhaps the single most influential person in the United States. His YouTube channel has 17 million subscribers. His podcast, The Joe Rogan Experience, which launched in 2009, has held the top spot on the Spotify charts consistently for the past five years; he records two or three episodes a week, each running to several hours. The former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang, whose campaign for universal basic income went viral after a Rogan appearance five years ago, calls him “the male Oprah.”

Rogan now lives in Austin, which has recently become known for its transformation from chilled-out live-music paradise to a miniature version of the Bay Area—similarly full of tech workers, but with fewer IN THIS HOUSE, WE BELIEVE … signs. Early in the coronavirus pandemic, the Texas capital saw the biggest net gain of remote employees of any major city in America; its downtown is now filled with cranes and new skyscrapers. It is also the center of the Roganverse, an intellectual firmament of manosphere influencers, productivity optimizers, stand-ups, and male-wellness gurus. Austin is at the nexus of a Venn diagram of “has culture,” “has gun ranges,” “has low taxes,” and “has kombucha.” The science and technology writer Tim Urban, who runs the popular Wait but Why website, told me that he moved to Austin from New York City because “I would have the experience of talking to someone I respect—some writer friend of mine, or someone who’s in a similar kind of career—and I would think, Oh, you’re in Austin too.”

The city attracts people with a distinct set of political positions that don’t exactly line up with either main party. They might be religious but are equally likely to be “spiritual.” They shoot guns but worry about seed oils. They are relaxed about gay people but often traditional about gender. They dabble with psychedelic drugs but worry about drinking caffeine first thing in the morning. Their numbers might be relatively small in electoral terms, but they transmit their values to the rest of America through podcasts, YouTube, and other platforms largely outside the view of mainstream media.

Go to a cocktail mixer, an ayahuasca party, or a Brazilian-jiu-jitsu gym here and you might run into Tim Ferriss, the author of The 4-Hour Workweek; or the podcasters Lex Fridman, Chris Williamson, Ryan Holiday, Michael Malice, or Aubrey Marcus. Elon Musk is so keen to get people to move to Texas that he is planning an entire community outside Austin called Snailbrook for workers at his Tesla Gigafactory and the Boring Company. (In case you’re wondering: Yes, every one of these men has been on Rogan’s podcast.) “It’s amazing that the arrival of one person could change a whole town, but it does feel like Rogan did that,” the journalist Sarah Hepola, who started her career at The Austin Chronicle, told me. “It’s a lot like the dot-com invasion of the ’90s, like something that happened to the town.”

Rogan and his fans are often called “heterodox,” which is funny, because this group has converged on a set of shared opinions, creating what you might call a heterodox orthodoxy: Diversity-and-inclusion initiatives mean that identity counts more than merit; COVID rules were too strict; the pandemic probably started with a lab leak in China; the January 6 insurrection was not as bad as liberals claim; gender medicine for children is out of control; the legacy media are scolding and biased; and so on. The heterodox sphere has low trust in institutions—the press, academia, the CDC—and prefers to listen to individuals. The Roganverse neatly caters to this audience because it is, in essence, a giant talk-show circuit: Go on The Joe Rogan Experience, and you can book another half dozen appearances on other shows to talk about what you said there.

I wanted to ask Rogan about all this: about the world that has coalesced around him, about the intellectual culture that he is exporting from Austin, about what his appeal might mean for November’s election. Past research by the marketing firm Morning Consult suggests that his fans are mostly male, predominantly white but a quarter Hispanic, and right-leaning but not locked in for Donald Trump. In other words, he has a nationwide base that both major parties would be delighted to win over—and that Kennedy was clearly desperate to recruit.

But one does not interview Joe Rogan. No human in history has needed publicity less, and he routinely turns down requests, including mine. So that’s how I ended up in the front row at the Comedy Mothership, cheerfully observing the two-drink minimum with the $8 canned water Liquid Death, face-to-groin with the male Oprah.

In May 2020, a couple of months into the pandemic, Rogan—then living in Los Angeles—visited Austin. “I went to a restaurant with my kids and they were like, ‘We don’t have to wear a mask?’ ” he recalled three years later. “Two months later, I lived here.” He bought an eight-bedroom house for $14.4 million just to the east of the city, backing onto Lake Austin. Barely half an hour from the congested traffic of downtown, Rogan’s house is set among scrubby hills, behind a gated driveway on a dead-end road. Although Rogan’s ability to make headlines blew up during the pandemic, he has been famous for a long time. He was in the cast of the ’90s sitcom NewsRadio and hosted NBC’s reality show Fear Factor, while building a parallel career as a mixed-martial-arts commentator. Follow his Instagram, and his tastes soon become apparent: energy drinks, killing wild animals, badly lit steaks, migraine-inducing AI graphics, dad-rock playlists, and shooting the breeze with his buddies.

The last of these has been greatly helped by the opening of the Comedy Mothership, in March 2023. The newest star here is Tony Hinchcliffe, who in April took part in Netflix’s gleefully offensive roast of Tom Brady and was featured on a Variety cover. The latter was a sign of a mood shift, given that he has never apologized for using an anti-Chinese slur onstage in 2021 to describe a fellow comic. Hinchcliffe hosts his own podcast, Kill Tony, which is now recorded at the Mothership, and he has helped set the tone for Austin’s new comedy scene. “There is no victim mentality whatsoever in Texas,” Hinchcliffe told Variety, adding, “It’s a different little island that we’ve created.” He was on the bill both nights I went to the Mothership, and wore a huge belt buckle with TONY HINCHCLIFFE written on it—presumably for situations in which he is both taking off his trousers and unable to remember who he is. He has very white teeth and a predatory grin, and he throws out jokes that double as tests: Can you handle this, wimp?

On the first night, Rogan was also accompanied by Shane Gillis, a puppy dog of a comedian. In 2019, Gillis was hired as a Saturday Night Live cast member and then fired four days later, after it was reported that he’d previously used an anti-Asian slur in a bit on his podcast and once described the director Judd Apatow as “gayer than ISIS.” Gillis apologized, lay low for a while, and built what is now the biggest podcast on the crowdfunding platform Patreon. He then self-financed his own comedy special, Live in Austin, which has 30 million views on YouTube—and promoted it with an appearance on The JRE. (Gillis has since been on Rogan’s show more than a dozen times.) His continued appeal thus demonstrated, Gillis returned to SNL as a host in February.

Rogan’s support of Gillis demonstrates why members of his inner circle are so loyal to him. Not only has Rogan personally boosted their careers on his podcast and in his club, but his popularity has forced the comedy industry to recalibrate its tolerance for offense. The best marketing slogan in American history has to be “People don’t want you to hear this, but …” What fans love about Rogan is the same thing his critics hate: an untamable curiosity that makes him open to plainly marginal ideas. One guest tells him that black holes are awesome. A second tells him that the periodic table needs to be updated because carbon has a “bisexual tone.” A third tells him that a deworming drug could wipe out COVID. He approaches all of them—tenured professors, harmless crackpots, peddlers of pseudoscience—with the same stoner wonderment.

The liberal case against Rogan usually references one of two culture-war flash points: COVID and gender. Media Matters for America, a progressive journalism-watchdog organization, has accused Rogan and his guests of using his podcast to “promote conspiracy theorists and push anti-trans rhetoric.”

In March 2013, the mixed martial artist Fallon Fox knocked out an opponent in 39 seconds and afterward revealed that she had been born male. A few days later, in an eight-minute riff on The JRE, Rogan said he was happy to call Fox “her,” but didn’t think she should compete against biological females. “I say if you had a dick at one point in time, you also have all the bone structure that comes with having a dick,” he added. Rogan’s choice of language aside, this was a claim that most Americans would deem uncontroversial: In general, biological males are physically stronger and faster than biological females. His comments prompted a media backlash, because he had violated an emerging consensus on the institutional left that trans women could compete fairly in women’s sports and that sex differences were overstated.

[Read: Helen Lewis on Trump’s red-pill podcast tour]

“Free health care—yes!” Rogan tells his audiences these days onstage in Austin, riffing on the political demands of the left. “Education for all—right on! … Men can get pregnant—fuck! I didn’t realize it was a package deal.”

During the pandemic, The JRE also drew audience members who were frustrated with the limits of acceptable discussion, at a time when Facebook and YouTube were banning or restricting what they labeled misinformation. Rogan didn’t accept the proposition that Americans should shut up and listen to mainstream experts, and that led to him hosting vaccine denialists and conspiracists, and promoting an unproven deworming drug as a treatment for COVID. True, he has a fact-checker—his producer Jamie Vernon, known to fans as Young Jamie, or “Pull That Up, Jamie,” after Rogan’s frequent instruction to him. But correcting what Rogan and his guests say about multiple conflicting studies during a live podcast is impossible. And to give you an idea of Vernon’s place in the hierarchy, he also makes Rogan coffee.

During the pandemic, the decision to host cranks such as Robert Malone—a researcher who claimed to have invented mRNA technology but sought to cast doubt on vaccines that employ it—resulted in a critical open letter signed by hundreds of health experts, a warning label from Spotify, and a gentle rebuke from the White House press secretary. However, Rogan also gave voice to those who felt that some COVID policies, such as outdoor masking and long-running school closures, were unsupported by evidence. A phrase that you will find throughout the right-wing and heterodox media ecosystems is noble lie. This refers to the fact that Anthony Fauci initially told regular people not to wear masks in part because he was worried about supply shortages for doctors and nurses, but it has come to stand in for the wider accusation that public-health experts did not trust Americans with complex data during the pandemic, and instead simply told them what to do.

You don’t have to look far in Austin to find the caucus of disaffected liberals that Rogan represents. On my second night at the Mothership, the ushers parked me next to Stephan, a house renovator whose business was booming thanks to all the rich newcomers to the city. He had left San Diego during the pandemic, he told me, because “they caution-taped the whole coastline.”

A few days earlier, I had met another of these “leftugees,” as one transplant jokingly nicknamed them, over coffee at Russell’s Bakery. The writer Alana Joblin Ain is a rabbi’s wife and a lifelong Democrat who before the pandemic lived happily in New York City and then San Francisco. In the summer of 2020, though, her children’s public school announced that it would remain closed into a second academic year, making her worry about the effect on their social skills and academic progress. She moved her son and daughter to a private school nearby—but on the penultimate day of the summer term in 2021, the head of school announced plans to convert its main bathrooms to gender-neutral ones, in part to help “kindergartners who [are] non-binary” and “kindergartners who are trans.”

When Ain questioned the policy—suggesting instead that some gender-neutral bathrooms should be provided alongside the existing girls’ and boys’ bathrooms—she was ostracized, she said. One father told her that her “wanting a space I feel more comfortable in, that’s a female space, reminded him of segregationists.” The dispute reminded her of other ways she’d felt alienated from the left. While helping her husband tend to his congregation, she had seen marital strife, substance abuse, suicide attempts, and other harms that she attributed to prolonged lockdowns.

And so she made the same journey that Rogan did, leaving California for Texas in 2022. She now runs an off-the-record discussion group called Moontower Verses, which meets in person to discuss culture-war topics. She doesn’t know how she will vote in November. Her experience echoes that of other Rogan fans on the coasts, for whom the pandemic brought the realization that their values differed from those around them; at the time, the persistence of masking was a visible symbol of that difference. “It’s the Democrats’ MAGA hat,” Rogan told a guest in November 2022. “They’re letting you know, I’m on the good team.” Move to Texas, went the promise, and you won’t have to see that anymore.

[Read: Joe Rogan’s show may be dumb. But is it actually deadly?]

A sense of left-wing overreach also drove the creation of the new University of Austin, or UATX. (The school’s website once boasted about Austin, “If it’s good enough for Elon Musk and Joe Rogan, it’s good enough for us.”) The announcement of the university’s launch in 2021 attracted immediate mockery, with The New York Times’ Nikole Hannah-Jones describing it as “Trump University at Austin,” after the former president’s scam-bucket operation.

That was unfair: UATX is run by serious academics, and has raised enough money to give free tuition to its entire founding class of 100. It has, however, leaned into the Roganite philosophy that people must tolerate wacko ideas in order to hear intriguingly heretical ones. In 2022, UATX offered a first taste of its politics when it ran a summer school, called Forbidden Courses, in Dallas. The speakers included UATX co-founder Bari Weiss (canceled by haters on Slack and Twitter), Peter Boghossian (canceled by Portland State University), Ayaan Hirsi Ali (canceled by a literal fatwa), Kathleen Stock (canceled by the University of Sussex), and my fellow Atlantic writer Thomas Chatterton Williams (inexplicably not canceled).

When I visited the UATX offices, in an Art Deco building in downtown Austin, the provost, Jacob Howland, told me that he wanted “to get the politics out of the classroom,” and that faculty members will have succeeded if the students can’t guess how they vote from what they say in class. Just as in Rogan’s comedy club, smartphones are banned in class—“so that students can’t be distracted by them, or, for example, record other students and tell the world, ‘Oh, you know, this student had this opinion, and it’s unacceptable, and I’m putting it out there on TikTok.’ ”

Many on the left, however, suspect that heterodox just means “right-wing and in denial.” An attendee at last year’s Forbidden Courses sent me a slide showing survey results about the students’ political leanings: Out of 29 respondents, 19 identified as conservative. One major UATX donor is Harlan Crow, the billionaire who has bankrolled Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas’s lifestyle for years; he sat in the back of some 2023 summer-school lectures. Another is the Austin-based venture capitalist Joe Lonsdale, who co-founded Palantir with Peter Thiel and others. He recently gave $1 million to a pro-Trump super PAC.

“We really are open to all comers,” Howland told me. He wondered whether some people on the left simply didn’t want to hear any debate.

The Joe Rogan coalition may indeed represent a real strand in American intellectual and political life—a normie suspicion of both MAGA hats and eternal masking, mixed with tolerance for kooky ideas. But it is fracturing.

“Anti-wokeness” once encompassed everyone who could agree that Drew Barrymore’s talk show was annoying, that some left-wing activists on TikTok were out of control, and that corporations were largely banging on about diversity to sell more products rather than out of a genuine commitment to human flourishing. Underneath those headline beliefs, however, were two distinct groups: disaffected liberals and actual conservatives, bound together by a common enemy. “Some of the people who seemed like my comrades on Twitter a while back,” Tim Urban told me, “I start to see some of them say stuff like ‘See, you start with gay marriage, and now you’ve got drag queens in this kindergarten class.’ And, well, hold on a second.”

Today, fractures are obvious across the wider anti-woke movement—and they must be serious, because people have started podcasting about them. Watching Rogan’s stand-up set, I realized that much of his culture-war material was now three or four years old; his podcast is one of the only places I still hear COVID mentioned, as Rogan relitigates the criticism he received during the pandemic. There’s a real tension in the Roganverse between the stated desire to escape polarization and the appeal of living in an endless 2020, when the sharp definition of the opposing sides yielded growing audiences and made unlikely political alliances possible.

Those contradictory impulses are evident in Austin. Jon Stokes, a co-founder of the AI company Symbolic, described the city to me as the “DMZ of the culture wars,” while the podcaster David Perell put it like this: “Moving to Austin is the geographical equivalent of saying ‘I don’t read the news anymore.’ ”

[Helen Lewis: What’s genuinely weird about the online right]

But national politics inevitably intrude. In front of the Texas capitol one sunny day, I found myself surrounded by a sea of pink and blue—a Christian rally against the “grooming” of children by LGBTQ activists through sex education in schools. A speaker was telling the crowd about a concealed, well-funded agenda centered on “the dismemberment of the heart and soul of your children.”

These are not Rogan’s politics. But relentless criticism from the left has pushed him and his fellow travelers closer to people who talk like this. Look at Elon Musk, who has developed an obsession with defeating the “woke mind virus” and an addiction to posting about his grievances.

At its worst, The Joe Rogan Experience is one of America’s top venues for rich and powerful people to complain about being publicly contradicted, and Rogan’s own feelings of kinship with the canceled mean that he has repeatedly hosted guests whose views are recklessly extreme. This unwise loyalty is most evident in his friendship with the conspiracy theorist Alex Jones. In 2022, the Infowars founder was ordered to pay nearly $1.5 billion in damages to the families of children killed in the Sandy Hook school shooting; his speculation that they were actors had led to a massive harassment campaign against them. At the trial, one father told the court that conspiracy theorists emboldened by Jones had claimed to have urinated on his 7-year-old son’s grave and threatened to dig up his body.

During his stand-up set, Rogan said that Jones was right about the existence of “false flags”—events staged by the government or provocateurs to discredit a cause. Then he whispered to himself that Jones had gotten “one thing wrong.” He had gotten a lot of things right too, Rogan said at normal volume. Then his voice dropped again: “It was a pretty big thing, though.”

Rogan’s sympathetic treatment of his friend demonstrates why power is better mediated through institutions than wielded by individuals: It’s too easy to be sympathetic to a man sitting in front of you, whom you know as a complete person, rather than to his distant, unseen victims. Also, it’s good to be open-minded, but not so much that your brain falls out.

If Rogan is the male Oprah, he is also the human embodiment of America’s vexed relationship with free speech: a complex tangle of arguments and conspiracy theories all boiled down into one short, swole man who likes to wear a fanny pack. Rogan is a guy who started a podcast in 2009 to smoke weed with his fellow comics and talk about martial arts—and who, like many Americans, has taken part in a great geographical sorting, moving to be closer to people whose values he shares. He speaks to people who feel silenced, both elite and normie, even as he’s turned the very idea that opinions like his are being “silenced” into a joke in itself. As I walked into the Comedy Mothership, I saw a sign on the wall. It read HECKLERS WILL BE ALIENATED.

This article appears in the October 2024 print edition with the headline “You Think You’re So Heterodox.” It has been updated to reflect that Robert F. Kennedy Jr. suspended his 2024 presidential campaign after the issue went to press.

What's Your Reaction?