What the Scopes Trial Was Really About

A new book on the famed 1920s court case traces a long-simmering culture war—and the fear that often drives both sides.

Thirty years ago, when I was an eighth grader at a small public school in central Pennsylvania, my biology teacher informed us that we would be studying evolution, which she described as “an alternative theory to the story of divine creation.” She was usually imperturbable, but I remember noticing that, just for a moment, her voice had a certain tone; her face, a certain expression—an uncanny mix of anxiety, fear, and rage.

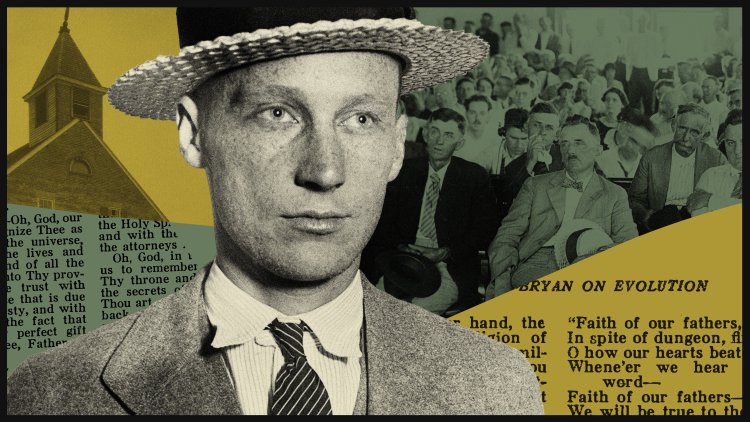

Roughly a century ago, the trial of John T. Scopes marked a flash point in an American culture war—between religious faith and science—that has been waged, in one form or another, to this day. In her new book, Keeping the Faith: God, Democracy, and the Trial That Riveted a Nation, Brenda Wineapple offers a definitive account of the 1925 trial, in which a small-town teacher was brought to court for teaching evolution and accused of undermining Christian creationism. But more important, Wineapple’s book provides a vivid account of how fear has always acted on our national consciousness—and a way of coming to terms with our own fractured political present.

The Scopes “monkey trial,” as the journalist H. L. Mencken, who covered the proceedings, called it, was never really about Scopes himself—the mild-mannered, 24-year-old biology instructor charged with violating Tennessee’s Butler Act, which prohibited the teaching of evolution in state-funded schools. Instead, it was about the competing ambitions of the two figures who would engage in a fervent battle over Scopes’s fate: Clarence Darrow, who took the defense, and William Jennings Bryan, the three-time Democratic nominee for president, who assumed the prosecution for the state.

[Read: When conservative parents revolt]

At the time of the trial, Darrow, a newly elected member of the National Committee of the ACLU, was committed to protecting academic freedom in primary and secondary schools, including the right to teach Darwinian evolution. His ambition, however, was much greater: to combat ignorance in all its forms, even if that meant disputing the Bible. Bryan, conversely, had made a career of placing Christian conservatism at the center of American politics. He thought academic freedom was dangerously overrated, especially in perilous times. As Wineapple writes, Bryan believed that “Darwin’s theory … allowed the strong to exploit the weak, and in the name of perfecting humans created humans without God but who think of themselves as gods.”

In Wineapple’s incisive treatment, the trial reveals how opponents in a cultural conflict can be similarly vulnerable and shortsighted. Throughout the book, she echoes another reporter who covered the proceedings, who wrote in one dispatch that, “at bottom, down in their hearts,” people on both sides of the debate were “equally at a loss.” The whole country did go a bit mad over the monkey trial: Some supposedly enlightened intellectuals—we might call them liberals today—attacked all things spiritual and religious (Darrow, for one, simply laughed at the “amen”s uttered in the courtroom). Many Christians galvanized around the value of unquestioned faith and rejected critical discourse. The KKK, who saw in Bryan a champion, murmured “America Forever” in their growing ranks. All the while, onlookers continued to purchase monkey souvenirs on the streets of Dayton, Tennessee, where the trial was held.

Many people around the world looked on with equal parts awe, embarrassment, and disgust. It was a moment when a relatively young country showed itself to be without tact or sense.

What those outside the United States might have viewed with bewilderment makes perfect sense to a historian like Wineapple. Modern notions of democracy and religious liberty were written into the founding of the United States, and yet a portion of its population has always looked to God and the Bible in moments of crisis. Even as the colonies struggled to survive in the 1740s, a religious “awakening” saw settlers turning to scripture and looking to evangelism to provide purpose in an uncertain world. The aftermath of World War I—defined by stark economic conditions, global mourning, and the wholesale destruction of Europe—roused a certain strain of Christian America, including people like Bryan, who believed that restoring religious ideas of tradition, unity, and purity would protect the country from turmoil.

The United States was never as traditional, unified, or pure as Bryan claimed, but that scarcely mattered to him or his followers. What did matter was his fear that conservatives were losing what they took to be their God-given place in the world. According to Wineapple, “Underlying this anxiety about the origins of humankind was of course another anxiety: that the vaunted superiority of the so-called Nordics may be a fiction.” Evolution implied that life originated, in the words of a commentator, “in the jungle” in Africa, not a divine paradise. Bryan’s defense of creationism doubled as an endorsement of a subset of white America. The Chicago Defender wrote that evolution “conflicts with the South’s idea of her own importance. Anything which tends to break down her doctrine of white superiority she fights.’”

But the prosecution also had an existential fear that Darrow’s defense, mocking and acerbic, neglected. Divine Creation, for Christians like Bryan, held within it the promise that human life amounted to something worthwhile. To Bryan, Scopes’s choice to teach Darwin was a self-conscious affront to the moral order—and any meaningful future for humanity. Bryan’s anxiety, as Wineapple describes it, reflected “the fear of the new, the different, the fear that if you admit knowledge or information, the world you know would be unrecognizable, alien, and terrifying.”

Wineapple’s account of the trial is a reminder of how political polarization is often an outgrowth of fear. And when the fate of a nation seems to be at stake, there can be little room for common ground. Bryan appealed to the Christian faith of his southern audience, arguing that only through adherence to dogma would America be preserved. In the words of Mencken, “To call a man a doubter in these parts is equal to accusing him of cannibalism.” Darrow, meanwhile, was afraid of being locked into a political and legal system that would inhibit progress in all its forms. And in the tumult, something very important was lost. Wineapple writes, “For all their differences and animosity, William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow were more alike in some ways than either of them would admit. The journalist William Allen White … characterized them as equally ardent, emotional, and committed to the ideal of a better world.” Their visions of this world, however, were starkly different.

[Read: The politics of fear itself]

It’s no spoiler, nor does it ruin the tension of Wineapple’s outstanding book, to reveal that the jury found Scopes guilty of violating the Butler Act, which would stand for another 42 years. Scopes was fined the minimum amount, $100. Bryan, Christian fundamentalists, and the anti-evolutionists claimed victory. And two weeks after the trial ended, the KKK marched on Washington, D.C., in throngs.

But according to Wineapple, Darrow had the last word: “The way of the world is all very, very weird … You may be sure that the powers of reaction and despotism never sleep … and in these days when conservatism is in the saddle, we have to be very watchful.” In 2024, most high-school teachers in the United States teach evolution—even if some might do so with the reluctance I witnessed in the eighth grade. Darrow needn’t have been so fearful that the circumstances surrounding the Scopes trial might permanently forestall social and political change. And yet, he was right to warn Americans that progress is never assured.

What's Your Reaction?