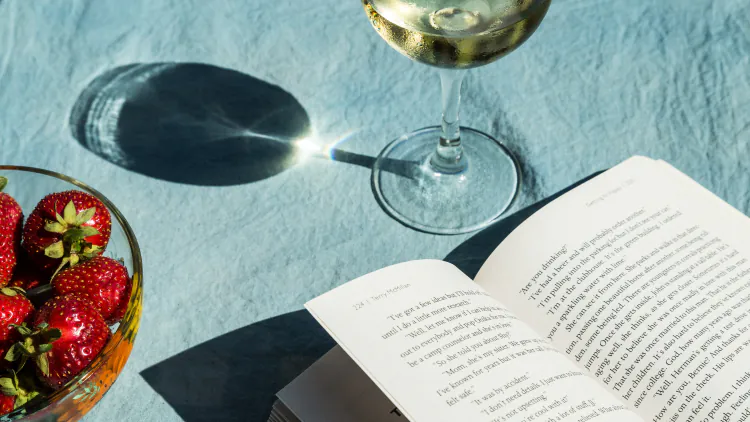

Six Books That Will Jolt Your Senses Awake

Reading can help us cultivate a more patient, attentive state of mind by highlighting the beauty present in our day-to-day lives.

Our minds these days are so easily distracted that noticing what’s right in front of us can be hard. Yes, the sun might be glancing off the snowdrifts, and the birds may be chirping away with blithe exuberance. But stress, grief, and anxiety—or, alternatively, excitement for the future—can make us tune out the images, fragrances, and noises at the edge of our consciousness.

But being attentive to the world is both possible and crucial. Sound, touch, smell, sight, and taste can draw us into a rapturous examination of the new, unfurling leaves on a tree or the antics of a honeybee. They can also help us enjoy the equally stimulating encounters of urban life, such as a fleeting impression of a stranger’s perfume on the sidewalk, or the exuberant cacophony of voices in a city square. In a harried world, such attunement to detail might require a bit of practice. Thankfully, literature can help us cultivate a more open and receptive state of mind.

The six books below show how sensory richness can make life more enticing. For the people in these novels and memoirs, mindfulness isn’t always easy. But they show how small moments can be rich with feeling, by recalling the cool repose of sitting under a tree or the complex flavors in a delicately aromatic broth. These books don’t just tell us to pay attention; they show us how.

Gazelle, by Rikki Ducornet

“Cassia, myrrh, lavender, orris, santal, rose,” recites the perfumer Ramses Ragab, while a young girl listens with fascination. Ducornet’s novel follows 13-year-old Elizabeth and her family as they spend a summer in 1950s Cairo. She is entranced by the glamor of urban Egyptian life: hotel balconies “delirious with flowering jasmine,” shaded moments in “the staggered shadow of the palm grove.” And Ramses, a friend of her father’s, introduces her to the beguiling practice of perfumery. But it isn’t all beauty and splendor; her parents’ marriage is disintegrating, and Elizabeth’s mother departs the family house to engage in conspicuous affairs. As her father retreats from the world to grieve, Elizabeth explores her temporary home by eating ripe dates and figs, admiring carved-ivory chess sets at the market, and drinking hot mint tea. By the end of the summer, she has made peace with the capricious, changeable nature of love: “In this world of water and roses,” she observes, “love spills from one person to the next; like fragrance, like water, its quality is restlessness.”

[Read: Trees have their own songs]

The Mezzanine, by Nicholson Baker

The daily rituals of an office job typically offer workers few opportunities to experience transcendent beauty. Not so for Howie, the protagonist of Baker’s eccentrically funny debut novel. The plot of The Mezzanine is deceptively banal: Howie goes to work, rips his shoelace, runs errands on his lunch break, and returns to his cubicle. But this day is made extraordinary through Howie’s cheerfully exuberant outlook on life. No object is too humble for his attention, and he waxes poetic about the beauty of escalators, paper bags, and the elegance of plastic elbow straws. Even the act of sweeping around his apartment furniture with “curving broom-strokes,” he enthuses, “made me see these familiar features of my room with freshened receptivity.” Baker’s writing combines humorous absurdity with the earnest anxieties of youth: Howie, who is 23, laments, “I was a man, but I was not nearly the magnitude of man I had hoped I might be.” But as he diligently navigates adult life, paying his bills and interpreting men’s-bathroom etiquette, he refuses to let his interest in the world become dulled. The novel reminds us that adulthood is richer when we retain a childlike “capacity for wonderment”—especially when it comes to the ordinary objects and rituals of our lives.

The Book of Salt, by Monique Truong

“At 27 rue de Fleurus,” the young chef Bình realizes ruefully, “even the furniture attracts more attention than I do.” In Truong’s historical-fiction novel, Bình is a Vietnamese immigrant in 20th-century Paris, where he becomes the private chef for Gertrude Stein and her partner, Alice B. Toklas. While the couple entertain Stein’s endless admirers, Bình labors in the kitchen. One elaborate dinner includes salade cancalaise (the recipe can be found in the real-life Toklas’s 1954 cookbook), where poached oysters become a “dollop of ocean fog” over tender potatoes, topped with truffles. Bình’s position in the household lets him quietly satirize the frivolous, fashionable lives of American expats in Paris. His appearance and speech, with “jagged seams between the French words,” mark him as a foreigner in Paris. But the city is still a refuge for Bình, who was born in Saigon and worked in a colonial officer’s kitchen before he was outed as gay and forced to leave home. Bình’s complicated relationship with the Catholic father who disowned him is pushed into the center when he receives a letter from home with “the familiar sting of salt … kitchen, sweat, tears or the sea.” Truong’s novel highlights the pleasure—and painful memories—that tastes and smells can evoke.

[Read: Each sentence is one you can feel]

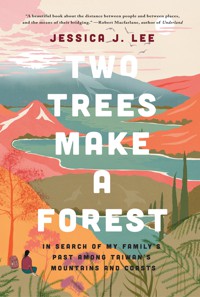

Two Trees Make a Forest: In Search of My Family’s Past Among Taiwan’s Mountains and Coasts, by Jessica J. Lee

During a difficult climb up Shuishe Mountain, in Taiwan, Lee asks herself whether nature can provide “arboreal answers to very human predicaments.” In Two Trees Make a Forest, she chronicles a three-month visit to Taiwan to reconnect with her heritage, a trip that leaves her feeling less “botanically adrift.” Like a winding hike, Lee’s memoir switches back and forth among family stories, history, and encounters with nature. Trekking through the Taiwanese mountains helps her connect “the human timescale of my family’s story”—her grandparents fled China in the 1940s and then immigrated to Canada in the ’70s—to the “green and unfurling” ecological history around her. At one point, Lee encounters a blooming Barringtonia asiatica tree by a waterfall, where “the slightest disturbance showered the ground in a floral rain.” The beauty of the tree prompts her to learn more about the species: Some botanical texts describe it as native to Taiwan, while others call it a “migrant tree”—much like Lee’s own family tree. Her memoir shows how a walk in the woods can give us a new perspective on questions of culture, heritage, and belonging.

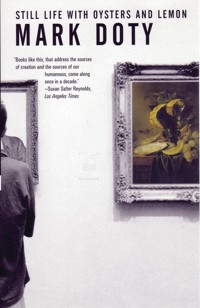

Still Life With Oysters and Lemon: On Objects and Intimacy, by Mark Doty

For Doty, a poet, attention is a form of secular faith: “A faith that if we look and look we will be surprised and we will be rewarded,” he explains, “a faith in the capacity of the object to carry meaning, to serve as a vessel.” In his 2001 memoir, Doty’s gaze lingers on great paintings and ordinary household objects alike. On a visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Doty stands reverentially before a Dutch still life, where a lemon is rendered in luminous detail: “that lovely, perishable, ordinary thing, held to scrutiny’s light.” Then there’s the half-carved violin decorating the home he shared with his partner, Wally, “like music emerging out of silence, or sculpture coming out of stone.” These object memories are tinged with loss: Wally spent the last years of his life in their home, dying from AIDS. But Doty’s memoir reminds us that the death of a loved one doesn’t extinguish the beauty and joy of the world. “Not that grief vanishes—far from it,” he writes, but “it begins in time to coexist with pleasure.” Close observations can be a source of intimacy and contemplation: They are “the best gestures we can make in the face of death.”

[Read: Recreation through the senses (from 1911)]

The Employees: A Workplace Novel of the 22nd Century, by Olga Ravn

What is there to sense in space? In Ravn’s speculative-fiction novel, shortlisted for the 2021 International Booker Prize, the isolated human and android employees of a spaceship find solace in the strange scents around them. The cold, impersonal environment makes the workers more attentive to small, earthy sensations, such as the “soil and oakmoss” odor of an object retrieved from an alien planet. These are familiar references to the human employees, but not to their half-human, half-software co-workers. Life on the spaceship is full of heady philosophical dilemmas, with the humanoid employees insisting that they’re also capable of consciousness and feelings. “I live,” one humanoid says, “the way numbers live, and the stars,” while another describes herself as a “flicker between 0 and 1 … part of a design that can’t be erased.” The evocative language softens a novel that’s also a biting satire of workplace surveillance. Conflict is inevitable, and during the tension that arises, one employee remarks: “Everything stands out so clearly, the way it does in grief, when all senses are awakened.”

What's Your Reaction?