The ‘Secret’ Gospel and a Scandalous New Episode in the Life of Jesus

A Columbia historian said he’d discovered a sacred text with clues to Jesus’s sexuality. Was it real?

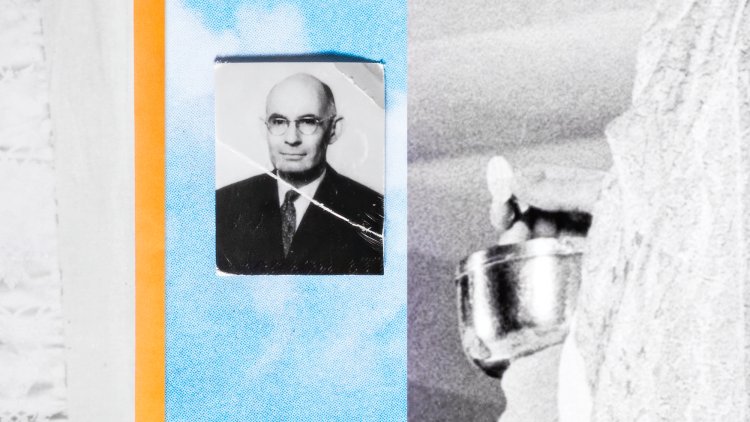

Photo-illustrations by Pacifico Silano

In the summer of 1958, Morton Smith, a newly hired Columbia University historian, traveled to an ancient monastery outside Jerusalem. In its library, he found what he said was a lost gospel. His announcement made international headlines. Scholars of the Bible would spend years debating the discovery’s significance for the history of Christianity. But in 1975, one of Smith’s colleagues went public with an extraordinary suggestion: The gospel was a fake. Its forger, the colleague believed, was Smith himself.

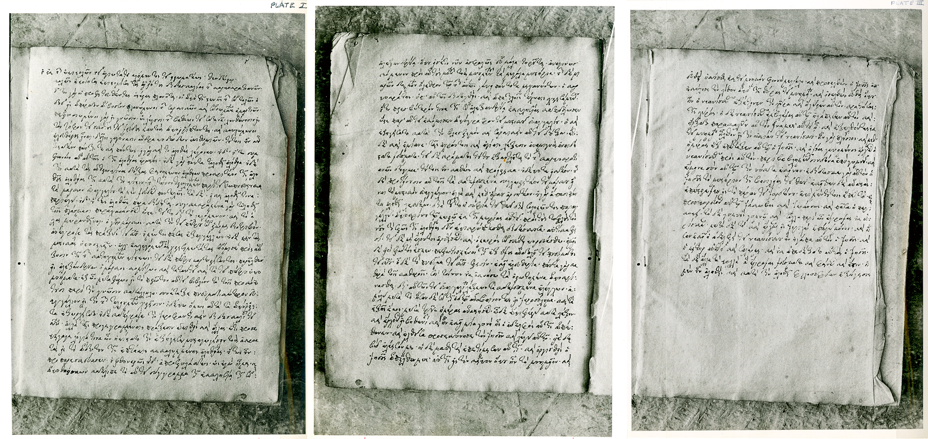

The manuscript, in handwritten Greek, ran two and a half pages, but one passage drew outsize attention. It depicted Jesus spending the night with a young man he’d raised from the dead. “The youth, looking upon [Jesus], loved him and began to beseech him that he might be with him,” it read. “And after six days Jesus told him what to do and in the evening the youth comes to him, wearing a linen cloth over his naked body. And he remained with him that night, for Jesus taught him the mystery of the kingdom of God.”

To devout Christians, the homoerotic subtext was obvious blasphemy. But Smith argued the opposite: His discovery, he believed, was part of an unknown, longer version of the Gospel of Mark, containing lost stories from about 50 C.E., making them the oldest known account of Jesus’s life—and, in Smith’s view, the truest.

Smith theorized that “Secret Mark,” as the text came to be called, portrayed a private baptism that Jesus reserved for his closest disciples: One by one and at night, he contended, Jesus hypnotized male followers into believing they’d risen to heaven and been freed from the laws of Moses. Smith argued that Jesus and his initiates may have concluded this liberation with a sexual act—a “completion of the spiritual union by physical union.”

Smith knew that orthodox believers would wholly reject his claims. To suggest that the central figure of Christianity—by tradition celibate—used gay sex as a path to God was an outrage. His academic colleagues were only slightly less aghast, but they couldn’t fully dismiss him. By the time Smith published his find—in a 454-page volume from Harvard University Press, with deeply erudite footnotes and appendixes, and in a popular book called The Secret Gospel—he’d been tenured by Columbia and Secret Mark had made the front page of The New York Times. Several major scholars had accepted the text as genuine.

None, however, bought Smith’s intimations of a gay Jesus, and almost none thought the text originated in the first century. They called his exegesis “science fiction,” “awash in speculation,” and “simply absurd.”

But a theologian named Quentin Quesnell went further: He believed that Smith had fabricated Secret Mark, as a “game,” to expose his field’s enormous blind spots. So little is known about the historical Jesus that one could paint “bizarre and scandalous” portraits of him, Quesnell wrote, without contradicting any of the established facts.

Peter Jeffery, a Princeton professor emeritus and MacArthur-genius-grant recipient, called Smith’s alleged forgery of Secret Mark “the most grandiose and reticulated ‘Fuck You’ ever perpetrated in the long and vituperative history of scholarship.”

Still, the debate over whether the manuscript is a fake—and Smith its forger—remains unsettled, and one of the bitterest in biblical studies. Over the past 50 years, it has inspired at least two conferences, seven scholarly books, and dozens of academic articles. Experts have scrutinized the manuscript’s language and the handwriting. They’ve compared it with authentic variants of Mark. They’ve puzzled over why no one before Smith—not even the early bishops who made exhaustive lists of heretical texts—had ever mentioned Secret Mark.

[From the July/August 2016 issue: Ariel Sabar on the unbelievable tale of Jesus’s wife]

One subject, however, has gone almost completely unexamined: Smith’s life outside the university. In the summer of 1991, several weeks after turning 76, Smith got a call from his friend Lee Avdoyan, an academic librarian whose Ph.D. Smith had supervised. Avdoyan was planning a trip to New York. He’d just finished writing a book and was eager for Smith’s feedback on some new research ideas. He also wanted Smith to meet his partner, Jim.

But Smith, whose health was declining, said he wasn’t up for a visit. He urged Avdoyan to forget research and to go into the world, have fun, live his life with Jim. “I have so many regrets,” Smith said.

Avdoyan, who’d come out years earlier, had long suspected that Smith was gay too. Had Smith realized only now how much of life he’d missed? He didn’t say, and Avdoyan didn’t press.

A week later, on July 11, 1991, two Columbia colleagues entered Smith’s Upper West Side apartment and found him dead. Beside Smith’s body were a bottle of vodka and a glass flecked with the powdery residue of what appeared to be pills. A plastic bag covered his head, its opening cinched around his neck; the New York City medical examiner’s office told me it ruled Smith’s death a suicide by asphyxiation. Smith’s will ordered his personal papers destroyed—“at once without being read.”

Outwardly, Morton Smith had been a proper, almost Victorian gentleman. Trim and prematurely bald, he spoke with a patrician accent, had a stiff gait, and wore three-piece suits, a Phi Beta Kappa key glinting from his vest pocket. His politics were similarly conservative. Yet when it came to religion, Smith was, in a colleague’s description, like “a little boy whose goal in life is to write curse words all over the altar in church, and then get caught.”

Smith had denied the forgery allegations but had relished—and stoked—the controversy. A provocateur who saw himself as an intellectual giant in a field of pious fools, he had for years sought opportunities to humiliate colleagues who promoted faith under the cover of scholarship. His caustic takedowns of their work, in prestigious journals and in face-to-face bullying at conferences, made him especially intimidating. He was “the kind of critic,” the Princeton professor Anthony Grafton once noted, “who makes grown scholars tear off their own heads for fear of reading his reviews.”

Smith cast the forgery claims as one more symptom of his field’s parochialism. “One should not suppose a text spurious,” he wrote, “simply because one dislikes what it says.” But Smith’s zealotry for his own reading of Secret Mark made colleagues wonder whether his stakes might also be more than academic.

Smith struck most people as a wry atheist. But before becoming a professor, at age 35, he had spent four years as a parish priest. Before turning the full force of his intellect against the dupes who believed in God, that is, Smith had, in a sense, been one of them.

Scholars who knew him well suspect that whatever triggered his break with the Church was the key to understanding his life and work, even if—perhaps especially if—Smith never spoke of it. The historian Albert Baumgarten, who was one of Smith’s first doctoral students at Columbia, believes that “something took place in Smith’s life that shook his certainty.”

Smith’s literary executor, the Harvard religion scholar Shaye Cohen, told me that he’d never ruled out the possibility of a “secret Morton,” a part of his past he’d hidden from even his closest colleagues.

Was there a secret Morton? I began my search with a visit to a pair of Texas scholars who had a new theory about Secret Mark. Not because their theory was fully convincing—it wasn’t—but because their analysis of the text pointed to why Secret Mark might be something other than early Christian scripture.

Brent Landau was teaching a religion seminar at the University of Texas at Austin in 2019 when he invited his colleague Geoffrey Smith to the class’s discussion of Secret Mark. The conversation inspired them to reexamine the evidence, a project that culminated in their 2023 book, The Secret Gospel of Mark.

Both men felt that the debate over the manuscript’s authenticity had become unmoored, an emotional proxy for broader fights among historians of Christianity. On one side were conservatives who saw the Church-authorized collection of Christian books—the New Testament—as divinely inspired. On the other were generally liberal scholars, who gave equal—or greater—historical weight to early Christian texts outside the New Testament canon.

As if to sell Secret Mark to their conservative colleagues—and help prove it authentic—liberals tended to deny the text’s sensuality. Its homoeroticism, many claimed, was nothing more than Morton Smith’s misreading. But to Landau and Geoffrey Smith, there was no escaping it: The text depicts Jesus spending the night with a desperate, lovestruck young man.

The circumstances of the discovery were admittedly complicated. What Morton Smith claimed to find at the monastery wasn’t some first edition of Secret Mark on papyrus. It was a copy of a letter that quotes Secret Mark. The letter’s author appeared to be the second-century Church father Clement of Alexandria. It had been transcribed, in an 18th-century Greek hand, onto the end pages of a printed 17th-century book. Smith had discovered those end pages, he said, while cataloging books in the monastery’s library.

Addressed to an unknown man named Theodore, the letter calls out Secret Mark’s sexual innuendo. Some early Christians may have seen the gospel as portraying “naked man with naked man,” Clement writes, but Clement condemns such views as false and “utterly shameless.”

Morton Smith gave them more credit. In a baffling passage in the Christian Bible’s Gospel of Mark, he noted, a nameless young man drops his linen garment and “flees naked” when Jesus is arrested at night in Gethsemane. If you spliced Secret Mark into canonical Mark, Morton Smith thought, you had an explanation: Jesus and his young follower had been caught in the act.

Brent Landau and Geoffrey Smith, the Texas scholars, immersed themselves in early Christian literature—looking at word choices, storylines, theological debates—to see where Secret Mark might fit. They concluded that it didn’t. It appeared, Landau told me, “as if somebody had gone through the Gospels and found all these instances where Jesus seemed to be in some sort of intimate or erotic relationship,” then “meshed them all together.”

A possibly larger problem was that the letter of “Clement” appeared to crib distinctive language from a Church history composed a century after Clement’s death. “Anyone who has ever caught a clever student cheating on an essay or during an exam will find the pattern familiar,” Smith and Landau write.

But who was this clever student? The answer, they suspected, might lie in the Greek Orthodox monastery where Smith claimed to find the manuscript, the only place ever known to possess it.

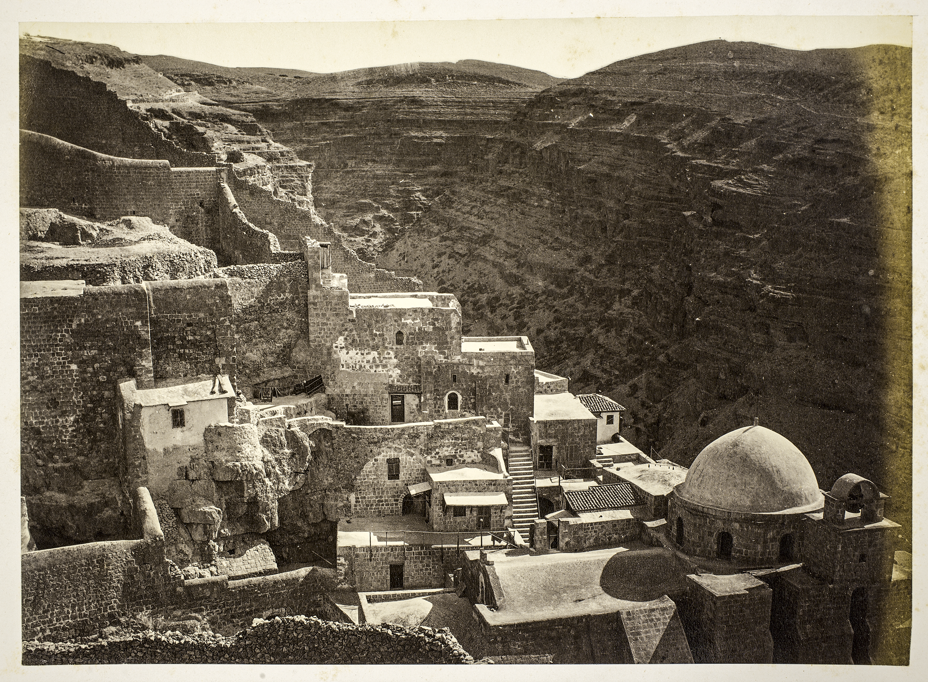

Mar Saba clings to a cliff in a desolate valley between Jerusalem and the Dead Sea. It was founded in 483 C.E. by a man named Sabas, who as a boy had fled an unhappy family in Cappadocia, in what is now Turkey. According to a sixth-century biography, the young Sabas “begged with tears” to join a small community of monks in Palestine, but an abbot sent him away. Monastic leaders worried that boys’ “feminine” faces would lead older monks astray. Sabas evidently came to agree. When he opened Mar Saba a few years later, he forbade admission to any adolescent “who had not yet covered his chin with a beard, because of the snares of the evil one.”

But communities of holy men faced other earthly temptations. Byzantine scholars, Landau discovered, had begun finding evidence, from as early as the fourth century, of same-sex couples: monks who shared a cell, traveled as a pair, and supported each other’s lifelong quest for spiritual perfection.

Hagiographies depict these relationships as a form of chaste, virtuous romance. When an Egyptian abbot praised the partnership of the fourth-century monks Cassian and Germanus, Cassian reports in one work, it “incited in us an even more ardent desire to preserve the perpetual love of our union.” Faced with separation, the sixth-century monks Symeon the Fool and John “kissed each other’s breast and drenched them with their tears,” according to a medieval text. Even Sabas’s own mentors, Euthymius and Theoctistus, an ancient biographer writes, were “so united … in spiritual affection that the two became indistinguishable.”

Whether these unions had a physical dimension is hard to know. But scholars suspect that at least some did, in part because of human nature, and in part because abbots took pains to separate and punish monks who they feared might cross a line. Horsiesios, a fourth-century head of Egypt’s Pachomian monasteries, warned the men in his charge against “evil friendship.” “You anxiously glance this way and that … then you give him what is (hidden) under the hem of your garment,” he wrote, in his “Instructions” to monks. “God himself, and his Christ Jesus, will pour out the wrath of his anger on you and on him.”

Horsiesios, like Sabas and other abbots, seemed to be drawing a boundary between holy and unholy unions among men of faith. And that got Landau and Smith thinking: Wasn’t whoever wrote the Clement letter doing the same thing, by urging readers not to mistake Jesus’s night with the young man for anything so “blasphemous and carnal” as “naked man with naked man”?

According to Sabas’s ancient biographer, 60 of his own monks once revolted against him, filled with such “fierce rage” that they used axes and shovels to destroy the tower he lived in. Their grievances are left vague; the monks had grown “bold in wickedness” and “shamelessness, not bearing to walk in the humble path of Christ but alleging excuses for their sins and inventing reasons to justify their passions.”

Was same-sex love—or lust—one of those sins? Ancient sources don’t say. But Landau and Smith theorize that the Clement letter was written by a Mar Saba monk during some “in-house” debate over the propriety of such unions.

If Sabas or his successors had enforced too hard a line on same-sex unions, might some monks have pushed back? Might one of them have faked a letter from two unimpeachable authorities—Clement and God—that presented Jesus himself as the model for intimate but still-sacred unions between men?

The text, Landau and Smith suspect, was composed between the fifth century, when the monastery opened, and the eighth century, when the Greek Orthodox Church adopted prayers for adelphopoiesis, or “brother making,” which blessed committed friendships between men. These new blessings, they argue, gave a kind of license to monastic couples, ending the need for subterfuge or protest.

After meeting Landau and Smith, I called Derek Krueger, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and an expert on sexuality in Byzantine monasticism. “It’s plausible,” he said, with some hesitation, when I asked about Smith and Landau’s theory. In monasteries, which isolate men from the world, the line between spiritual and erotic love could certainly blur: As Krueger put it in a 2011 article, “One monk’s agape might be another monk’s eros.” Still, no ancient stories defending the virtue of monk couples—none he knew of, anyway—took the guise of a lost gospel.

The Texas scholars grant the roughness of their theory. They have no evidence of any such debate at Mar Saba, and no explanation for why a monk there would have felt compelled to copy such a letter in the 18th century. Nor can they rule out the text being a better fit for later eras, in which they have less expertise.

The one person their book seems determined to exonerate is Morton Smith. Their case for ending all discussion of him as a possible forger—a case that leans heavily on ad hominem attacks against his critics and on reflexively charitable interpretations of his motives—is their least convincing. Their eagerness to clear Smith also conflicts with what they acknowledge is a giant evidentiary hole: No one, to public knowledge, has ever scientifically tested the physical manuscript. (The manuscript is thought to remain in the archives of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem, a notoriously cloistered institution that rarely admits scholars for any reason and did not respond to Smith and Landau’s—or my—requests for comment. No one has reported seeing the manuscript since the early 1980s.)

Another source of potentially significant evidence, scholars suspect, is the part of Smith’s life he kept from the world. Over three months, in visits to the churches where Smith had once sought a home, I pieced together the story of a priest whose crises of faith and identity prefigure his discovery of a secretly gay Jesus.

Robert Morton Smith (he went by his middle name) was born in 1915, the only child of an older, well-to-do couple in the Philadelphia suburb of Bryn Athyn. The town is the American headquarters of the conservative branch of the New Church, a Christian movement inspired by the 18th-century mystic Emanuel Swedenborg. Smith’s mother was a fervent follower. His father manufactured stained glass for churches across the mid-Atlantic.

Smith was a star student at a New Church high school, and he internalized a view of men and women as incomplete—each “a divided or half person,” as Swedenborg put it—until perfected by marriage. Swedenborg’s invocations of “foul liaisons,” “unmentionable sexual unions,” and “a foulness that is contrary to the order of nature” have been read as explicit condemnations of homosexuality.

The world beyond the Church was nearly as unforgiving. Doctors deemed homosexuality a mental illness, and state laws criminalized sodomy. In 1920, Harvard University formed a “secret court” to investigate—and expel—students suspected of homosexual conduct. Two of the men convicted by the court would take their own life.

Smith eventually left his family’s Church, but he was not yet ready to abandon Christianity. In 1938, after graduating from Harvard College and entering Harvard Divinity School, he abruptly joined the Episcopal Church. The Christian leader who set Smith on a path to the Episcopal priesthood, I discovered, was a gay Marxist revolutionary.

Frederic Hastings Smyth was a successful, MIT-trained chemist when he decided, in his mid-30s, to give up his career. He became an Anglican priest and developed a complex theology that saw communism as a precondition for the kingdom of heaven on Earth. (He believed that Marxists could be talked out of their atheism after the revolution.)

In 1936, Hastings Smyth opened a kind of monastery steps from Harvard’s campus, calling it the Oratory of St. Mary and St. Michael. He hoped to recruit brilliant students as leaders of a proletarian overthrow of capitalism. The oratory, where he lived with a few young male disciples, was decorated with Baroque Italian furniture and scented with liturgical candles, incense, and the gourmet meals he cooked for students who dropped in for political discussion and Mass. Smith was a committed traditionalist, but something about Hastings Smyth must have so compelled him that he was willing to overlook the priest’s insurrectionary politics. In December 1938, six days after Hastings Smyth baptized him, Morton Smith was admitted to Holy Communion at the oratory.

Hastings Smyth didn’t live with a boyfriend in Cambridge, as he’d done as a layman in Europe. But the oratory was nonetheless stigmatized as “homosexual”—and surveilled by J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI. Within a few years, Hastings Smyth began to worry that some students weren’t coming for Marxist revolution, as he’d hoped, but to work out their sexuality. “It is dangerous for us,” he wrote to a friend, in a letter I found in a Toronto archive. “We are too exciting for them.”

Harvard Divinity School came to see the renegade priest as a menace to students, having “done none of these men any good” and “one or two of them some harm,” Willard Sperry, the school’s dean, wrote in an April 1940 letter. Sperry was particularly concerned about one divinity student, “a rather unstable fellow emotionally, who has given us all a good deal of anxiety for fear he will have some kind of nervous break-down. I have the Hygiene Dept. watching him.” Sperry doesn’t name the student, but in hundreds of pages of archival records I could find no Harvard divinity student more closely associated with Hastings Smyth in the late 1930s than Morton Smith.

Just five months after his baptism, Smith took his first step toward ordination, applying in the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania. I asked Paul Corby Finney—an art historian who maintained a long correspondence with Smith and spent late nights drinking with him in the 1980s—what had initially attracted Smith to the priesthood. “He said he was very much in love with the idea of a community of men worshipping God.”

Smith sought contacts in the Episcopal Church’s Anglo-Catholic, or “high church,” wing, with which Hastings Smyth had identified. Though free of the doctrinal strictures and hierarchies of the Roman Catholic Church, it retained much of Catholicism’s drama: its elaborate ceremonies; its vestments, bells, and candles—and its veneration of celibacy.

Scholars of sexuality have portrayed Anglo-Catholicism as a pre-1950s refuge for highly educated queer clergy, a “stained-glass closet” that permitted coded displays of femininity and homoeroticism among male priests “as long as they remained chastely celibate or at least avoided scandal,” the historian Timothy W. Jones has written. According to the scholar David Hilliard, Anglo-Catholicism, as a fringe of the Episcopal Church, was “both elitist and nonconformist, combining a sense of superiority with a rebellion against existing authority … It provided an environment in which homosexual men could express in a socially acceptable way their dissent from heterosexual orthodoxy.”

In 1940, Smith traveled to Jerusalem on a two-year research fellowship. He ended up staying until 1944, unable to recross the Atlantic during the world war. In Jerusalem’s Old City, he befriended a Greek Orthodox clergyman, who invited him to Mar Saba. Smith traveled to the monastery by donkey in 1942 and lived with its monks for a month. (It was on a later visit, in 1958, that he’d say he found Secret Mark.)

In the candlelit darkness of its church, where the brothers prayed for six hours each night, Smith gained a “new understanding of worship as a means of disorientation,” he recalled in his book The Secret Gospel, “dazzling the mind and destroying its sense of reality.”

“I knew what was happening,” he wrote, “but I relaxed and enjoyed it.”

When Smith returned to America in 1944, his quest for ordination was in trouble.

Pennsylvania’s Episcopal bishop wanted Smith to enroll at the Episcopal Divinity School, but its dean told the bishop that Smith had a reputation as “cynical, skeptical, lacking in convictions, highly cantankerous.” The faculty’s unanimous opinion was that “for all his brilliant academic qualifications,” Smith was “not otherwise fitted to serve in the ministry.”

The bishop got no more assuring a report from Father David Norton Jr., the rector of a working-class Boston church where Smith had run a boys’ club. “He’s interested in such questions as: ‘What other basis is there for deciding the morality of an action than the ultimate pleasure or pain it will bring to the doer?’ ” Norton wrote. “I often feel that he takes a line of argument and follows it as an intellectual game rather than for the purpose of coming at the truth.”

But in March 1946, for reasons the record doesn’t reflect, the Pennsylvania bishop ordained Smith anyway, then quickly transferred him out of state. After 18 months at a Baltimore church, Smith moved back to Massachusetts, where he saw firsthand what became of people who tried to hide their true self in the Church.

In September 1948, while serving at St. Luke’s Church, in blue-collar Boston, Smith officiated the marriage of a restaurant hostess and a bartender. A month later, headlines appeared in the Boston newspapers: The hostess was still married to another man. A judge convicted her of polygamy and gave her a suspended six-month prison sentence and a year’s probation.

Her lawyer told the court that she’d married the bartender “only to protect the baby she had thought was coming,” a pregnancy that apparently ended in miscarriage. The woman, a relative told me, was no believer. But she’d entered a church—and lied—to give her forbidden relationship and baby the appearance of respectability.

News articles name Smith as the priest who sanctified the marriage, but don’t say how much he knew of the woman’s past. The episode can’t have helped his already precarious standing in the Massachusetts diocese, where one church had declined to make him vicar, despite desperately needing one, and where the bishop, Norman Nash, never licensed him to minister, making his 17 months in pulpits there a possible canonical violation.

Church archives show that Smith had exactly one backer in Massachusetts: the Right Reverend Raymond Heron, who as suffragan bishop was second in command to Nash.

Around the time Smith performed the polygamous marriage, Heron began appearing in a horrifying string of front-page stories. The 62-year-old priest, who’d never married, had for years befriended troubled boys and invited them to live with him, on his farm, as paid “chore boys.” On August 5, 1948, one of Heron’s former chore boys, Frederick Pike, 19, returned, intending to rob Heron. When Pike entered the farmhouse and found one of his successors—a 17-year-old who’d lived with Heron since he was 10—Pike shot the boy twice in the head, went to a shed for an axe, and then bludgeoned the boy’s body with its blunt end, taking a 15-minute break between drubbings.

When Heron came home, Pike fired wild shots at him but missed. He briefly held the bishop hostage, stole his wallet, and escaped in Heron’s car before police captured him in Providence, Rhode Island. A jury convicted Pike of first-degree murder, and a judge sentenced him to death. (The penalty was later commuted, and Pike was released from prison in the 1970s.)

The Living Church, a prominent Episcopal magazine, regretted the death of Heron’s 17-year-old “protégé” but praised Heron’s farm as “a means of healthy life and wage earning for boys in whom the Bishop has taken an interest.” With Pike’s appeals keeping the story in the news, Heron married his new, Church-appointed secretary. The Boston papers prominently covered the “private” and “surprise morning ceremony.”

A few months later, in the spring of 1949, Smith published a bristling journal article. Titled “Psychiatric Practice and Christian Dogma,” it cast Christianity as incompatible with mental health. All of Smith’s examples were sexual: a girl who compulsively masturbates; a young “homosexual” who as an adolescent had “helpful” friendships with older men; a divorcée who wants a new husband “tied down before the progress of her infirmity … becomes obvious.”

Unlike a good psychiatrist, who guides such people to self-acceptance, Smith wrote, the good pastor has to condemn them as sinners. The Church, that is, requires a man to sacrifice this world for the next, regardless of “his happiness or his health or his very life.” In Smith’s view, there was no midpoint between sin and salvation. Which meant one thing: “Ecclesiastics who do not believe the teachings of their Church should have the decency to leave it.”

On September 18, 1949, Smith led his last service as an active priest.

Over the next few years, Smith tried to figure out, as a scholar, how faith seduces and deludes. He had earned a Ph.D. from Hebrew University in Jerusalem and was working on a second doctorate, from Harvard Divinity School, when Brown University hired him in 1950 as an instructor in biblical literature.

One of his first research ideas there was for a “psychiatric study” of what spiritual training does to the minds of monks. Next he began an obsessive hunt for pagan sources for the canonical Gospel of Mark. But neither of these projects bore out: A mentor cautioned against “psychoanalytical fantasies,” and scholars found his arguments about Mark’s paganism unconvincing, derailing a book he’d been close to finishing.

These intellectual rejections were compounded by professional ones. Near the start of 1954, Brown told Smith that it wasn’t renewing his contract. And despite recommendations from renowned scholars, he was passed over for jobs at Yale, Cornell, and the University of Chicago.

No less painful, perhaps, was that Smith’s washout at Brown separated him from his best friend. Atanas Todor Madjoucoff was a handsome Arabic interpreter, born in Palestine to Greek Orthodox parents. He and Smith had met in Jerusalem, apparently in the 1940s, and reunited in 1951, when Smith took a year’s research leave from Brown. Madjoucoff accompanied Smith to monastery libraries around Greece, and in August 1952, according to passenger manifests, they boarded the SS Excambion together, in Piraeus, for an 18-day voyage to Boston.

In Providence, Smith found Madjoucoff an apartment around the corner from his. But shortly after Brown told Smith that his time there was up, Madjoucoff changed his last name, married a woman he’d met through his church, and moved to the suburbs.

In the 1950s, nothing was going the way Smith wanted it to. He’d failed at the priesthood, and now he was failing at academia. Off campus, gay and lesbian people faced a brutal new wave of persecution, with President Dwight Eisenhower effectively banning them from government employment and a U.S. Senate subcommittee calling “homosexuals and other sex perverts” security risks who “must be treated as transgressors and dealt with accordingly.”

Smith floundered for three years before a job offer came from Columbia. It wasn’t in religion—the field he’d long aspired to join—but in ancient history. Smith accepted, and used his very first summer there, in 1958, to return to Mar Saba. He waited more than two years—until Columbia gave him tenure—to announce his “accidental discovery,” as he called it, of a surreptitiously gay Jesus.

After settling in New York, Smith paid regular visits to Rhode Island to see Madjoucoff. Their relationship was filled with private outings, personal confidences, and gifts to Madjoucoff’s children from a man they called “Uncle Morton.”

“There were secrets they kept among themselves,” Madjoucoff’s daughter told me, secrets her father didn’t even share with her mother. (“No one really knows” whether the men were lovers, she said; she and her eldest brother told me they had no evidence that their father was anything but straight.) Madjoucoff’s obituary (he died in 2019) called Smith his “lifelong friend.”

In the late 1970s, Smith had a brief relationship with an openly gay Columbia student. But not until after retirement did Smith attempt to come out.

In February 1989, an NYU dean published a screed against student protesters who had demanded classes on “gay, lesbian and bisexual issues.” The dean lamented that any campus would treat homosexuality as “an acceptable form of normative behavior.”

The article appeared in an obscure journal published by a group of conservative professors opposed to campus activism. Smith had long supported the group, but the dean’s words got to him. “Homosexuality is a way of life followed by millions of adult Americans,” Smith typed, in a letter to the journal’s editors. “Attempts to require adherence to a norm from which figures so various as King David, Socrates, Michael Angelo, Shakespeare, and Frederick the Great happily deviated, should disturb a Dean with even a rudimentary knowledge of cultural history.

“The most shameful thing,” Smith continued, was that students had to protest “to get an honest and complete course on a subject of legitimate concern to many students, faculty members, and administrators.” Equally worrisome, Smith wrote, was that the dean, as an administrator, had the power to discriminate against gay job seekers.

“I must ask that you publish this letter,” he wrote.

Smith didn’t identify his own sexual orientation, but he’d stood up for himself in a public way. On a copy of the letter he mailed to Lee Avdoyan, his friend and former student, Smith wrote, “Herewith my ‘coming-out’ article. I never expected to write one, but I’m getting old and irritable, and [the dean’s article] was just too much.” The journal never published the letter.

After Smith’s suicide, associates opened his briefcase and found an incongruous, plastic-cased ID among the workaday address books and pocket calendars. “This is to certify,” it said, “that The Reverend Robert M. Smith is a priest.” He’d held on to it until his dying day.

Smith left Madjoucoff nearly $320,000, a sum many times greater than every other beneficiary’s. His will also left something more personal: any three belongings Madjoucoff desired.

As they walked through Smith’s apartment, Madjoucoff ’s wife noticed a photograph of her husband. Something about its intimacy surprised her, their eldest son told me. It wasn’t the sort of portrait that men she knew kept of other men.

“You can take that,” she told her husband.

But Madjoucoff choked up. He couldn’t bring himself to do it.

If Smith saw Christianity as threatening his health, happiness, and “very life,” as he’d suggested in that 1949 essay, how far might he have gone to discredit the faith?

In an era of rampant homophobia, Christian leaders such as Frederic Hastings Smyth and Raymond Heron had inspired dreams of liberty—of new life—in vulnerable boys and young men. But they could no sooner save others than save themselves. The celibate priesthood was less a sanctuary for gay men than a treacherous hiding place.

The parallels between Smith’s disillusioning years in the Church and the peculiar Jesus he found at Mar Saba are hard to miss: Smith’s Jesus is a manipulator whose baptisms foster the illusion of sexual freedom among psychologically fragile men. But Jesus is arrested at Gethsemane, and the young man who flees naked—a seeker of “the mystery of the kingdom of God”—winds up exposed and alone.

Smith had more than enough motive to forge Secret Mark. As a polymath scholar with contacts across the Mediterranean, he almost certainly had the means. For as long as he’d been a professor, he had taken a childlike, at times sadistic, glee in making the world of religion squirm. A hoax on the Church that betrayed him would have surpassed anything else he had done, but it wouldn’t have been out of character.

Nor would it have been his only work of fiction. Smith’s personal papers were destroyed, as he’d instructed, but his professional ones were donated to the Jewish Theological Seminary. Among them I found an unpublished short story, undated but bearing his New York address.

If Secret Mark was a youthful fantasy of salvation through forbidden sex, this other tale was, in a sense, the reality Smith found.

“Once upon a time,” in a “golden age,” the story begins, a young man carried on a “clandestine affair” with a lover he visited “by way of the back stairs.” But the relationship was doomed: Not only was the “young lady” betrothed to someone else; her mother shunned the man because of his “total inacceptability.”

When one day the mother nearly caught them in the act, the man grabbed his fallen clothes and “took refuge in the closet,” only to have the mother cluelessly pull it shut.

“The latch clicked,” Smith wrote. “There was no knob on the inside.”

The story stops mid-sentence, in the middle of its second page. The man is trapped and alone, and outside it’s beautiful and radiant, and then nothing. The story’s title—“The Skeleton in the Closet”—is the only clue Smith leaves to the part he’s left unwritten.

This article appears in the April 2024 print edition with the headline “The Secret Gospel.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What's Your Reaction?