The Magic of Old-Growth Forests

Photographing some of the oldest—and largest—living organisms on the planet

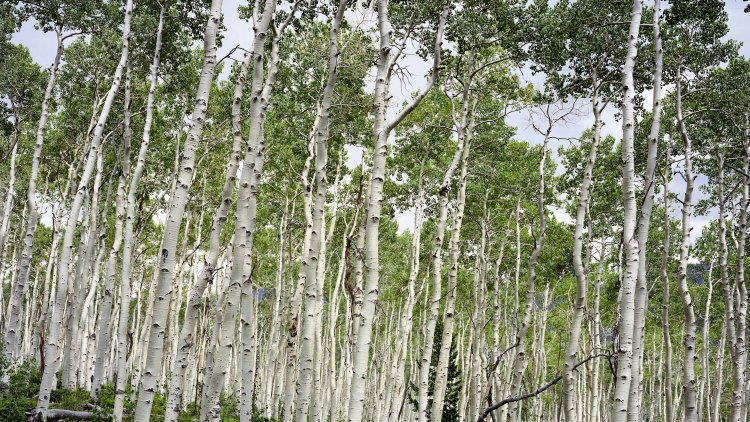

Photograph by Mitch Epstein

When I was a boy, I loved climbing the old oak trees in New Orleans City Park. I would hang from their branches and fling my legs into the air with unfettered delight. I would scoot my way up the trees’ twisting limbs until I was a dozen feet off the ground and could see the park with new eyes. These were the same trees my mother climbed as a young girl, and the same ones my own children climb when we travel back to my hometown to visit. Live oaks can live for centuries, and the memories made among them can span generations.

For his most recent project, Old Growth, the photographer Mitch Epstein traveled around the United States to document some of the country’s most ancient trees: big-leaf maples, eastern white pines, sequoias, redwoods, birches. Definitions vary, but Epstein considers old-growth forests to be areas that have been untouched by humans and allowed to regenerate on their own terms. Much of this land in North America has been destroyed in the centuries since European settlers arrived on the continent; Epstein wants his photographs to call attention to what remains, in order to protect it.

One site Epstein visited on his journey was Utah’s Fishlake National Forest, where he spent time with Pando: a collection of 47,000 aspen trunks connected to the same root system. Covering 106 acres and weighing about 13.2 million pounds, Pando is one of the largest living organisms on the planet. Epstein has written that it “creates an illusion of infinity.”

The trees in Old Growth have been around for at least hundreds of years, some for more than 3,000. According to a recent federal report, the biggest threat that American old-growth trees face is destruction by wildfires, which are exacerbated by climate change. Indeed, a warming planet poses risks to trees of all ages and in all settings. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina killed 2,000 trees in City Park. Future storms, made more intense by climate change, could soon make such destruction seem quaint. It might feel like the time has passed for us to change course, but Epstein insists that’s not the case. “How did we get here?” he asked me, “and how do we find a way to realign our relationship to the resources that we have been graced by here on Earth?”

This article appears in the July/August 2024 print edition with the headline “Interconnected.”

What's Your Reaction?