An Oblique and Beautiful Book

The Children's Bach is a striking picture of how ravaged a life can be when unmoored from any responsibility, and of how necessary it is to take care of others.

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

Until last fall, I had never heard of Helen Garner—something that’s hard for me to believe. The Australian author, now 81 and treasured down under, has barely been published in the United States. But over the past few months, the imprint Pantheon has been releasing new editions of her backlist, and these books are mind-blowingly good. In an essay this week, Judith Shulevitz wrote about two of Garner’s novels: Monkey Grip, from 1977, and The Children’s Bach, considered her masterpiece, from 1984. In both books, Garner depicts the free-loving and living atmosphere of the late 1970s, at a moment when an era of liberation was beginning to curdle. Shulevitz has identified the subtle, almost secret, way that Garner chose to critique the louche attitudes of her times: by writing children into her stories and showing how deeply affected they are by all the sex and drugs swirling around them. The essay reveals much about Garner’s understated style. Beyond its insightfulness, I hope it also brings readers to The Children’s Bach, which I now consider one of my all-time favorite novels.

First, here are four new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

- A vision of the city as a live organism

- Six cult classics you have to read

- What Orwell really feared

- “Half Moon, Small Cloud” — a poem by John Updike

Garner is a prolific diarist, and in one entry, which the novelist Rumaan Alam quotes in his introduction to the new edition of The Children’s Bach, she writes, “I will never be a great writer. The best I can do is write books that are small but oblique enough to stick in people’s gullets so that they remember them.” She's wrong on the first count—she is a great writer—but she is correct about her books being oblique. I can’t describe exactly what The Children’s Bach is about beyond the reader being dropped into the Melbourne suburbs in the early 1980s to follow a group of lost people as their lives collide with one another’s. “It’s a fast, graceful dance,” Shulevitz writes. “Point of view is passed from one character to another and back again, like a ballerina being spun from one dancer’s arm to the next.”

Garner doesn’t explain much; she just immerses you in stories of malaise and yearning. What she captures with incredible economy—the whole book is only about 150 pages—is a desperation among these characters for authentic living. The sentences seem to sing: Here’s one passage from early on, setting up the relationship between Dexter, who is the book’s protagonist, if there is one, and Elizabeth, an old college friend, whom he reconnects with after 18 years:

How strange it is that in a city the size of Melbourne it is possible for two people who have lived almost as sister and brother for five years as students to move away from each other without even saying goodbye, to conduct the business of their lives within a couple miles of each other’s daily rounds, and yet never to cross each other’s paths. To marry, to have children; to fail at one thing and take up another, to drink and dance in public places, to buy food at supermarkets and petrol at service stations, to read of the same murders in the same newspapers, to shiver in the same cold mornings, and yet never to bump into each other.

To me, this strange and beautiful book is a striking picture of how ravaged a life can be when unmoored from any responsibility, and of how necessary it is to take care of others in order to feel whole. Dexter’s path to this realization progresses with that obliqueness that Garner intended. But when late in the book she offers a gut punch of insight about where he has arrived emotionally, it’s done with sentences that will stay with me for a long time: “This was modern life, then, this seamless logic, this common sense, this silent tit-for-tat. This was what people did. He did not like it. He hated it. But he was in its moral universe now, and he could never go back.”

A Child’s-Eye View of 1970s Debauchery

By Judith Shulevitz

The brilliant novels of Helen Garner depict her generation’s embrace of freedom, but also the sad consequences.

What to Read

The Fifth Season, by N. K. Jemisin

The end of The Fifth Season has my favorite section of any speculative-fiction or fantasy novel: a huge glossary of terms such as stone eaters, commless, and orogene that appears after the plot stops, giving the reader a hand in interpreting the wildly unconventional world of the book. And it’s helpful here, because the complex, intricate story takes place on a supercontinent called the Stillness that is on the verge of its regular apocalypse, known as the “fifth season,” a period of catastrophic climate change. “Orogenes,” who can use thermal energy to create seismic events, are considered dangerous people, and most are in hiding, shunned from society. Jemisin’s main character, Essun, is one of them, hiding her true identity as she works as a teacher in her village. She returns home one day to find that her husband has murdered her son and kidnapped her daughter—both of whom inherited her powers. She must journey to save her daughter, accompanied by a mysterious child, while the world around her crumbles. After reading a few chapters of The Fifth Season, you’ll be immersed in this new world and its intricacies, enraptured by the ways this society’s structures shed light on the worst realities of our own. — Bekah Waalkes

From our list: Seven books that will make you put down your phone

Out Next Week

???? The Museum of Other People: From Colonial Acquisitions to Cosmopolitan Exhibitions, by Adam Kuper

???? Negative Space, by Gillian Linden

???? New Cold Wars: China’s Rise, Russia’s Invasion, and America’s Struggle to Defend the West, by David E. Sanger

Your Weekend Read

Our Last Great Adventure

By Doris Kearns Goodwin

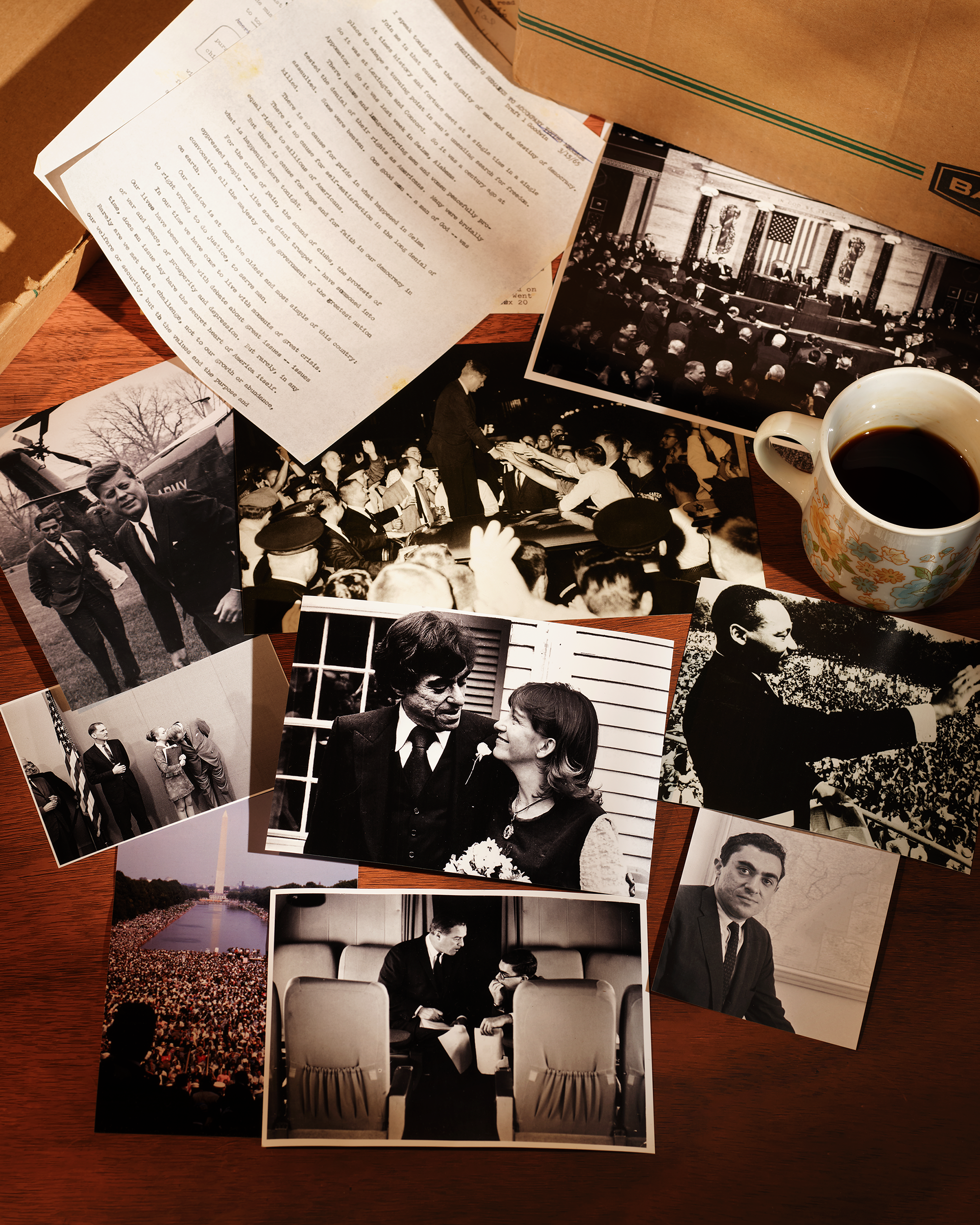

“It’s now or never,” he said, announcing that the time had finally come to unpack and examine the 300 boxes of material he had dragged along with us during 40 years of marriage. Dick had saved everything relating to his time in public service in the 1960s as a speechwriter for and adviser to John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, Robert F. Kennedy, and Eugene McCarthy: reams of White House memos, diaries, initial drafts of speeches annotated by presidents and presidential hopefuls, newspaper clippings, scrapbooks, photographs, menus—a mass that would prove to contain a unique and comprehensive archive of a pivotal era. Dick had been involved in a remarkable number of defining moments.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What's Your Reaction?