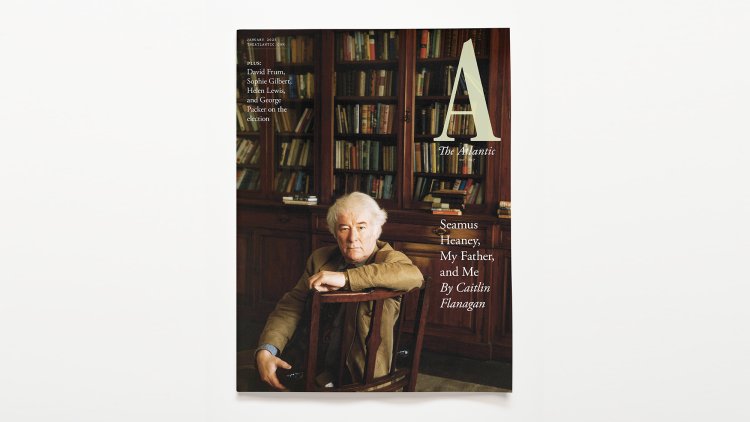

<em>The Atlantic</em>’s January Cover Story: Caitlin Flanagan on What the Poet Seamus Heaney Gave Her

For The Atlantic’s January cover story, “Walk on Air Against Your Better Judgment,” staff writer Caitlin Flanagan writes for the first time about growing up with the Nobel Prize–winning Irish poet Seamus Heaney, and what her family’s close friendship with the Heaney family offered her. She writes: “Seamus gave me the one thing I desperately needed growing up in that crazy family: my certificate of belonging.” In 1970, Heaney arrived in California with his family to spend the academic year in the UC Berkeley English department, where Caitlin’s father, Tom, was a professor. Caitlin’s parents were almost 20 years older than the Heaneys, and took the visiting family under their wing. “Berkeley swings like a swing-boat, has all the colour of the fairground and as much incense burning as a high altar in the Vatican,” Heaney wrote to his editor shortly after arriving. The following year the Heaneys were back in Ireland, and so were the Flanagans, for Tom’s sabbatical. Long before his Nobel

For The Atlantic’s January cover story, “Walk on Air Against Your Better Judgment,” staff writer Caitlin Flanagan writes for the first time about growing up with the Nobel Prize–winning Irish poet Seamus Heaney, and what her family’s close friendship with the Heaney family offered her. She writes: “Seamus gave me the one thing I desperately needed growing up in that crazy family: my certificate of belonging.”

In 1970, Heaney arrived in California with his family to spend the academic year in the UC Berkeley English department, where Caitlin’s father, Tom, was a professor. Caitlin’s parents were almost 20 years older than the Heaneys, and took the visiting family under their wing. “Berkeley swings like a swing-boat, has all the colour of the fairground and as much incense burning as a high altar in the Vatican,” Heaney wrote to his editor shortly after arriving. The following year the Heaneys were back in Ireland, and so were the Flanagans, for Tom’s sabbatical.

Long before his Nobel Prize in Literature and international acclaim, Heaney was a family friend to the Flanagans and a second father to Caitlin. Heaney often compared his bond with Tom as one between father and son: “I supposed you’re destined to be a father-figure of sorts to me,” he wrote to Tom in 1974. “Blooming awful.” Caitlin babysat the Heaney children; once, Heaney built the Flanagans a bookcase. Decades later, Heaney would write Tom’s obituary for The New York Review of Books.

The families were so close that on the occasion of Caitlin and her sister’s baptisms into the Catholic Church in 1971, Heaney wrote the girls a poem. Caitlin writes, “When Seamus stood up and read the poem, ‘Baptism: for Ellen and Kate Flanagan,’ I accepted everything—all of it, all at once: poetry, God, and myself. For half a century, I’ve kept the piece of onionskin he typed that poem on, so thin that it’s almost translucent. It’s a blessing on the long, strange project of being Kate Flanagan.” (The poem is being published for the first time, alongside the cover story.)

In the cover story, Caitlin explores Heaney as a person and poet, and the extraordinary impact that he and his wife, Marie, had on her. Caitlin writes: “He had a sense of obligation to others that in anyone else would be incapacitating. Once, when my own children were small, I took them to visit Seamus and Marie. After tea and hugs, we climbed into the taxi, and the driver said, ‘So you’ve been to see the great man.’ Almost around the corner was a billboard with his picture on it, promoting a new documentary. By his later years, there was no escaping himself, and the endless duties the role entailed. He may have fantasized about ditching those duties, but he never shirked them.”

In writing about Heaney, Caitlin is also writing about relationships, kindness, and the indelible impression the people we love leave on our lives. A few months ago, Caitlin made her first visit to Heaney’s grave in Ireland, a full decade after he died. She writes of the visit: “We can’t escape it: losing the people we love and need the most. Each death has to be countenanced as a fact, squared away in the record books. But there are people so well known to us, so loved, that death is one more thing that can be turned to air.”

Caitlin Flanagan’s “Walk on Air Against Your Better Judgment” was published today at TheAtlantic.com. Please reach out with any questions or requests to interview Caitlin on her writing.

Press Contacts:

Anna Bross and Paul Jackson | The Atlantic

[email protected]

What's Your Reaction?