Zamboni

A short story

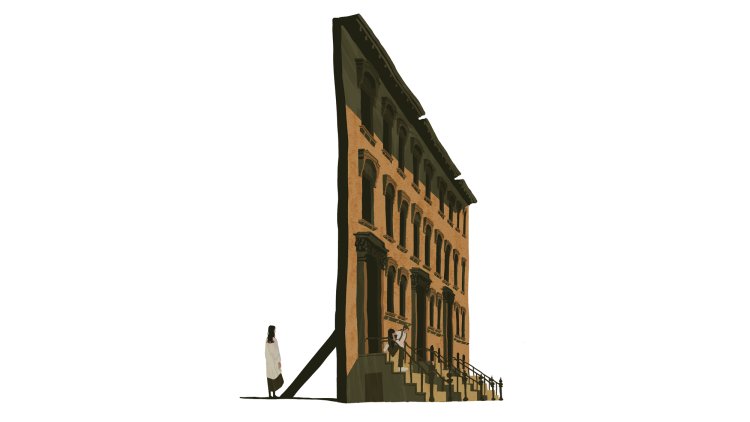

Illustrations by Katherine Lam

The children don’t look real. It’s because of what they’re wearing—it’s the color of their clothes. None of the T-shirts has any language or images—no slogans or athletes’ names, no animals or action figures. Color conveying only the idea of color. Later, she can’t remember what she noticed except that the colors were very bright. That and the fact that she didn’t recognize any of the children’s faces, though this is the playground of her own child’s school.

The children seem to be arranged in groups of three or four. They aren’t moving. Well, they move—some have rubber balls that they hold out to other nearby children and then retract. But they stay in position, as if stuck to a mark on the blacktop. They make no sound. They’re waiting.

Today is the beginning of her child’s spring break. Otherwise he’d be here now, playing on the blacktop himself, in the jersey that he insists on wearing whenever it’s not in the wash. It was white once, but now it’s a pale gray-brown, a sort of kneecap color. He’s wearing the shirt at the gym where she booked him for a day of ninja/parkour camp so she could go to work. She and her husband had thought about taking a vacation somewhere, but it’s not convenient for him to do that right now, and they can’t afford a trip anyway. She doesn’t mind; she likes being home in the neighborhood, where everything is familiar.

Hurrying down the block, she starts to forget about the unreal children. The colors were probably only ordinary pinks and yellows, the children, after all, only ordinary children, the kind who pass from the mind as soon as they pass out of sight. But then she notices the Zamboni. It’s the size of a small dump truck, and the word ZAMBONI is written on the front. She can think of no possible explanation for what it’s doing here. Then she sees a tent with water bottles and snacks. Oh cool, she thinks, a movie.

When she picks up her son that afternoon, she tells him that they should go by the school, there’s something happening, but she won’t say what; it’s a surprise. The children have disappeared, but the street is packed with trailers. Young people are everywhere, carrying lengths of metal, black boxes with knobs on them, clipboards, garment bags. They must have just finished shooting. The Zamboni has moved to the other end of the block. It has done what it came to do: It has driven through a dining shed.

All along one side of the street are splintered pieces of wood. Chairs have been crushed, tables knocked sideways. White plates have frisbeed and shattered into white pieces. There was no dining shed here that morning; the crew must have constructed and then demolished it in a matter of hours. One corner of the structure still stands, just solid enough to signify what it is meant to be.

Does this mean we won’t have to go back to school? her child asks.

I’m sure they’ll be done by the time spring break is over.

Can I be in the movie?

Maybe, she says, which is what she tells him when she knows something is impossible but it’s not her fault.

She tries to get him to stand in the middle of the shed and pretend that he’s the one who knocked it down so she can take a picture. Look like the Hulk, she tells him, and flexes her arms. He won’t do it. He won’t even step off the sidewalk. Come on, she says, we’ll send it to Daddy. She mimes a ninja kick in the direction of a table. But he backs away from her. He’s worried they’ll get in trouble. She wants to say that this is their school, their street, that the movie people are only borrowing it. She thinks how much better most things would be if he would just do what she says.

Now one of the movie men approaches, fat extension cords coiled around both arms. He’s going to ask them to keep moving, please. She pretends not to see him. Okay, she says to the child, let’s go.

That was a Zamboni, she says. It smooths the ice at a skating rink.

How?

It melts it.

It melts the ice?

Just the top layer. The ice gets scratched by all the skates. You have to melt it to make the ice smooth again. She skated often as a child but can barely remember what it felt like anymore. She’s never taken her son skating. It seems like too much effort. But he’s her child. How could anything be too much effort?

There’s a restaurant on the corner, and it’s funny to notice that just past the last bit of rubble from the movie dining shed is an actual dining shed. Her child stops. The movie chairs are pale wood. The restaurant chairs are white metal. But right between them is one table, set for dinner with plates and silverware and two clear glasses, with two chairs painted blue. Is this one real? her child asks. I think so, she says. Or no. She can’t tell.

The restaurant doesn’t open for another 10 minutes. She can see the waiters at the bar. They’re finishing their own meal in what looks like silence; each one has a white apron folded over the back of his chair. She and the child could stay and watch—see if anyone comes to the door, asks to sit outside, is guided to the blue chairs. But even then, how would they know for sure if the people were ordinary diners? They could be movie people testing out the props. They could be rehearsing.

Even better, she and her son could have dinner here and request the table themselves. If they were given the blue chairs, they would know that the table was real, because they themselves were certainly real. But her husband won’t like that. He’s planning to cook tonight; he’s going to be home early. She says they should come back tomorrow—tomorrow they can see if it’s still there.

In the morning, one of the moms at school has posted an article about the movie on Instagram. A famous actor is starring in it, and it’s not a children’s movie, as she’d assumed—because of the Zamboni and the color of the children’s clothes, or because of the children themselves. The article names the director, who is known for black comedies and the discomfiting avant-garde, and it includes photos of the famous actor in his previous roles. But no other details have been released; the article says nothing of plot. She taps to the woman’s next post, which is about the new war: a cute photo of her daughter eating a doughnut and the words Another thousand murdered children. Imagine if yours was one of them.

Spring break seems to go on and on; she can’t wait for it to be over. The school gives a shape to her days. She sees the same people at the same time. The supers sorting the trash. The man carrying boxes of pastries into the coffee shop—there goes the baker with his tray like always. The dog people exchanging their phone numbers. The joggers passing the speed-walking Orthodox. The families like hers, iteration after iteration. When this routine and all its regulars are gone, she feels vaguely afraid, as if her child has only her and his father to depend on.

When she sees other parents in the neighborhood now, all they talk about is the movie. I saw the branches first, one of her friends says.

What does she mean, the branches?

Didn’t you see? Fake budding branches clamped in the trees, like garlands, filling out the gaps. They must have needed it to be later in the spring.

Another friend has noticed the sod. The scuffed-up stretch behind the blacktop is lush with new grass. Someone asked the crew if they would leave the grass when they were done, but they said no—they had to roll it back up again. The fake branches, of course, will come down. Perhaps they’re already gone, she’s not sure. Each time she walks by, she forgets to look closely at the trees. Each time she forgets to look for the blue chairs.

Today her child is on a playdate. Her husband thinks she overschedules him. Why can’t she just let him play at home? But she likes to see other parents, she likes to see where they live. It makes her feel part of things, as if life is holding on to her with many small buckles and clasps. Besides, it’s impossible to get enough work done when her child is home; he has so many things he wants to say to her—mostly, that he’s bored.

Her husband has agreed to get their son in a few hours, so she’s free to go into the office; she can catch up on everything she’s been putting off. But she can’t seem to move toward the train. She always goes straight from the school to the station, always at the same time. This late in the morning, without the steady flow of people bearing her along, she finds that she just can’t do it. She decides to take her laptop to a coffee shop instead.

On the way, she walks by the school. She’s so used to the film crew now that she almost misses him—the star of the movie himself—sitting on the front steps.

The actor doesn’t look anything like an ordinary person; immediately he looks like a celebrity. He is obviously more beautiful than a normal person. But looking at him, she sees many images of him at once, all the movies and gossip stories and fragrance campaigns. She knows, vaguely, that he played heartthrobs, then bad boys, and has aged lately into serious art. He might be 50, but it’s hard to tell; the record of all his faces works on his face, on what she can see of it now. It’s a bit like looking at her husband and son—otherwise ordinary people she can see only through a sheaf of her own precious impressions.

Then she sees that the actor is wearing an orthopedic boot on his right foot. The boot brings her back to reality. Probably it would be rude to mention it.

Hi! she says. My kid goes here. I just wanted to say we’re all so excited about the movie.

Thank you so much, the actor says.

You must be almost done, right?

No, no, far from.

I just mean because spring break is ending.

Oh right. Done at the school. Yes, don’t worry, we’ll be out of your hair soon.

Not at all, we’ve loved having you. Why is she speaking like some kind of representative for the community? She’s not even on the PTA.

Walking away, she notices that she’s not embarrassed by how awkward the interaction was. She understands that the actor is a real person, but—barely. She could have said anything and it wouldn’t have mattered.

A few hours later, she’s deep in a document when her husband calls. Is she still in the neighborhood? Would it be terrible to ask if she could? A client, a meeting, he owes her. She’ll have to pick up her son after all.

How was the playdate? she asks him.

Fun.

What did you do?

We played.

What did you play?

World Cup.

What’s that?

She’s boring her child, but she persists. It’s her job to teach him manners. I ask this, and you say that, and here you go, thank you very much—like something passed back and forth, the point being less the thing itself than the transaction of attention, the agreement that you both exist, saying I and you and placing the right amount but not too much into the other person’s hands.

It’s soccer but inside, and each time someone misses a goal you have to—

Unfortunately, as soon as he’s talking, she realizes she’s forgotten to listen. Sounds super fun, she says.

She wants to pay attention, but it’s hard. Sometimes she has to force her son to talk, but other times he talks just to make her listen. Can I tell you something? he’ll ask. And after she says yes, she realizes there was nothing he had to tell her. He just wanted her to turn her face to him. She can see him working to come up with something to say. All children do this, of course; sometimes her husband does it too. Can I tell you something? She waits. Did you know volcanoes still exist?

People say he looks like his father, and that makes her jealous. It’s not that she wishes he had a small version of her face; she just wants it to be obvious that they belong together. She doesn’t think he looks like anyone, really; not his father, not even himself. His face is always changing, always disorienting her. She recognizes most of all his knees, his shoulders, the circle of his belly.

The actor is right where she left him. He’s leaning back on the steps, one leg bent and the other stretched flat. That’s him, she tells her son from a discreet distance. He’s the star.

When they reach him, her son immediately asks: What’s on your foot?

A boot.

It looks like a spaceman’s boot.

Thank you, that makes it sound cooler than it is. The actor squints in the sunlight; you wouldn’t think he could make that face. I hear you go to school here.

How do you know?

I know your mom.

I’m in first grade.

Super. The actor looks like he’s been polite twice to this local fan and now he wants the conversation to be over.

All of us have been wondering what the movie is about, she says.

We’re not supposed to say.

Just the briefest summary.

There’s an NDA.

What if I promise not to tell anyone else?

It’s not really appropriate for kids, he says.

She tells him not to worry, it’ll go over her son’s head.

My character is a teacher at the school who’s lost his wife. When I come back to work, everyone is really nice to me. My colleagues give me long hugs in the lounge. But almost right away, everyone moves on. The bell rings every 45 minutes. First period, second period, like a ladder through the day. But this can’t be real, I keep thinking. I would do anything to bring her back.

Then one day the children in my class begin to change. At first you think I’m imagining it, that they’re little flashbacks maybe. But I’m not imagining it. My wife used to sing this old song when she thought I wasn’t listening. She’ll be coming ’round the mountain when she comes. She’ll be driving six white horses when she comes. I thought it was something she’d sing to our own children, when we finally chose to have them. I had this image of her holding and rocking and singing some child that song. One day I’m walking down the hallway behind a girl and I hear her. She’s humming. Then she sings: Oh we’ll all go out to meet her when she comes. Oh we’ll all go out to meet her when she comes. Oh we’ll all go out to meet her, we’ll all go out to meet her, we’ll all go out to meet her when she comes. Close-up. Tears in my eyes.

In class, I notice a boy is sitting just like my wife did. She had this way of perching on a chair, her knees pulled up against her chest. It looked like something you’d do by a fire, in the grasslands, not at the kitchen table—like how prehistoric people would have sat in case a predator came. It bugged me. Couldn’t she just sit comfortably?

Parents start coming in to tell me they’re worried. Their child isn’t sleeping. My wife had terrible insomnia. She rarely drifted off before 1 or 2. At school, the children look exhausted, poor guys. We’ve stopped doing the coursework by this point. I let them nap in class.

Sometimes at night my wife would get frightened and I would need to comfort her. I would stand by the bed and rub her back until she fell asleep. I don’t know how much it helped—it wasn’t enough, in the end, to stop her from doing what she did. I never wanted to see her in pain, but those were good moments, when I was attending to her fear. She got me thinking that maybe there really was something bad out there, and she needed my protection. Or maybe the feeling was that nothing was out there, and we were the only ones, and I liked that too.

When the children get the same frightened look, I start doing it in class. I have them put their heads down on their desks and I turn off the lights and I walk down each row, humming about her coming ’round the mountain and giving them each a little pat between the shoulder blades.

I can see that they’re suffering in the same way she suffered. Worse, because they don’t know what’s happening, why they’re being made to do and feel these things. I feel pretty guilty about it, but I can’t stop. First period, second period, the sound of the bell muffled as if by my own hand. Shh, I think, don’t disturb them. It’s like the classroom is very small and down somewhere very low, and the light comes through a distant hole. They can do that with the camera.

By the end, actual events start replicating, here inside the school. I’ll just tell you one. She was a competitive ice-skater as a kid. One day the water freezes in the water fountains. The pipes burst overnight, flooding the halls, and by the time the children come in the next morning, smooth black ice covers the floor from the nurse’s office to the auditorium.

She stopped skating when she was 14 or 15, because she fell and broke her leg. So I slip in the hallway and break my leg. She had to miss a recital as a result. It was her first big disappointment, the first thing that was taken from her. She had to sit and watch her friends perform in their bright costumes, and then in came the Zamboni, oozing like a great mechanized slug over all traces of choreography, telling her it was over, she had missed her chance.

But worst are the children, too many for one man to rock and sing to, their drooping heads, their soft faces on which I’m stamping this record of experience, and all of them looking up at me, knowing how I wasted her time.

The funny thing is that, though I seem to have this power to force the children to embody her, I had no power over my wife herself. I could never make her do what I wanted, what I thought was good for her. By the end, she only laughed at me, when she laughed at all. Eventually I begin to wonder if it’s me who’s in charge, or her, because as much as I think I made this happen, I have no idea how to stop it. I go sit in the back of the classroom and look at the blackboard, hoping that something, anything, will be written there. And: credits.

That’s a bad story, says her son.

That’s not polite, she says.

I told you it wasn’t for kids, the actor says. But it’ll be beautifully shot.

From across the street come a woman and two children. They’re selling candy. The brother and sister are in front, each bearing their own cardboard box, each brand of candy in a tidy row. They stop in front of the actor. They must have no idea he’s a celebrity; they think he’s just sitting there. Chocolate? they say.

The actor pats his pockets, but he’s not carrying anything. Tom! He calls over a man on the crew, his assistant maybe, who gives each child some cash. The man waves off the candy.

Watching the family go, she explains to the actor and his assistant that there’s a new shelter in the neighborhood for migrants. It’s one of the reasons her husband has started talking about leaving the city; he says he doesn’t want their son to have to see so much sadness, though she suspects that what their son sees is mainly kids with candy.

The other boy is wearing a jersey from the same team as her son, and socks with flip-flops so small for him, most of his heel is flat on the ground. She wonders what these children see when they look at the school. The shelter must be zoned for a different district because, as far as she knows, none of the residents goes here. Perhaps this place always looks like a film set to them.

Those kids should be in school, the assistant says.

It’s spring break, she reminds him.

Still, terrible to see them being used that way.

I don’t know, the actor says. What are they supposed to do? It’s not like they can afford nannies.

But making the children walk in front like that. Because people are more likely to pay attention to the hardship of children. Less likely to resent their suffering. More willing to give money for it.

What would you prefer, the actor asks, for the parents to make them walk behind?

She thinks they both have a point: The children raise the stakes of the story. It would be dumb not to use them.

When the brother and sister get to the playground, they turn inside the chain-link fence while the mother waits. The movie children have filed out to the blacktop again to assemble in their groups of three and four. The siblings go among them, proffering their candy, but they look confused—none of the other kids acknowledges them. There are no parents here; they must be realizing how strange that is. Something is wrong with this place, with these unreal children.

Can I be in the movie? her son asks again.

Bad luck, the assistant says. It’s already been cast.

Can I be extra?

An extra, the assistant says.

That’s what I said.

No, not possible, let’s not be rude, she starts to say, but the actor answers: You’d have to come all day and do whatever you’re told.

I can do that!

And you can’t talk, or play, until you’re told to talk and play, and then it has to be the right way.

Please, I want to.

What do you think, Tom?

No, she thinks. Not my child. His face would be caught forever, expressing someone else’s feelings in someone else’s story. She pictures something being stretched over his head, taut as a swimming cap, with that synthetic smell, that tightness over the brow.

The assistant shakes his head. I’m afraid we’re all set, he says.

Just put him in a scene, Tom.

You know I can’t.

But look what I can do, her son says. He runs up the school steps. At the top, he puts his palms on the railing, leans his belly against it, lifts his feet off the ground, and hovers there. She’s embarrassed. She’s about to tell him they need to stop bothering these grown-ups, that it’s time to go home, when he jumps down. He leaps to the side, spins, descends a step, leaps back, ducks under the railing. On the other side he does the same—leaps, spins, descends, leaps, ducks—and again. Back and forth he goes, down and farther down, bowing each time below the black bar that marks the center. It’s like he’s knitting one side of the school to the other. Sometimes he adds a kick, an extra twirl. Ninja moves, ballet moves, moves so particular to his own peculiar self, they have no name and she can think only: That’s him, there he goes. He makes no sound, and neither do the men, watching on the sidewalk, surprised into respect by the opacity of what he’s making, its buoyancy, its gravity.

When he reaches the bottom of the stairs, he stops. That’s just a little dance, he says.

Sunday is the last day of spring break, and her husband tells her to relax; he’ll take their son out. She asks where, and he says not to worry about it—they’re having father-son time. Go back to bed, he says. She watches them get ready to leave, the two people she loves most. The boy is talking about how he auditioned for the movie. He says he’ll show his father the dance.

Mom, he says, Dad and I are going to talk about places we can move to. He says I can use his Google when we’re on the bus.

His Google?

So I can look up pictures.

Hypothetically move to, her husband says. It’s just for fun. Tell her.

Sure, their child says. For fun.

Tomorrow, she thinks, everything will go back to normal. They’ll go to school, she’ll join the people flowing to the train. She tidies and makes coffee. She gets out a book. The apartment is so quiet. By lunchtime, she wants her family back. Her husband sends her a laughing face—she’s so pathetic, it’s sweet. He says she can meet them at the restaurant by the school in half an hour.

She passes the school’s front steps; she forgets, again, to look closely at the trees. Only one trailer is left—they’re clearing out just in time. A man steps into her path. Ma’am, he says, could you wait here for just a moment? We’re trying to get a last shot.

He’s holding up one hand like a crossing guard, looking expectantly at the walkie-talkie in the other. She does as she’s told. She waits a minute. Two.

Excuse me but how long will this take? I just need to get to the next block.

Not long. Five minutes tops.

I’m in a hurry. I have to meet my family.

We’ll get you through as quick as we can.

This is a little ridiculous. Can’t I just go on the other side of the street?

I’m sorry, that’s not possible.

How can it not be possible? Look, where’s Tom? Tom knows me.

I don’t know who you’re talking about.

You’re acting like this is some issue of public safety, like you’re a police officer. But you don’t have any actual power, do you? To stop people from moving through their own neighborhood?

[From the September 2023 issue: “The Comebacker,” a short story by Dave Eggers]

And yet she doesn’t push past him. She’s so close, she can see the restaurant; she can see the people at the sidewalk tables; she can see them in the dining shed. They’re laughing and eating and lifting their glasses as if for the same toast. And yes, right there—that’s her family. Her child’s back is to her. Around the edges of his head and shoulders, she can see another outline, the same shape, just taller and broader, like a prediction of the future—the shape of his father.

She realizes they’re at the table with the blue chairs. Her son must have remembered. But there were only two of those chairs—where will she sit when she gets there? A band of fear snaps around her, like it’s a crisis, like she can’t just walk over and pull up another seat. But she can’t, because she’s trapped here, waiting. She can’t see the cameras, but she knows they must be rolling. If she starts to run, the cameras will catch her. She’ll be in the movie.

This story appears in the January 2025 print edition.

What's Your Reaction?