William Whitworth’s Legacy

The longtime editor of The Atlantic believed in the sanctity of facts—and the need to fortify the magazine continually with new voices and writing driven by ideas.

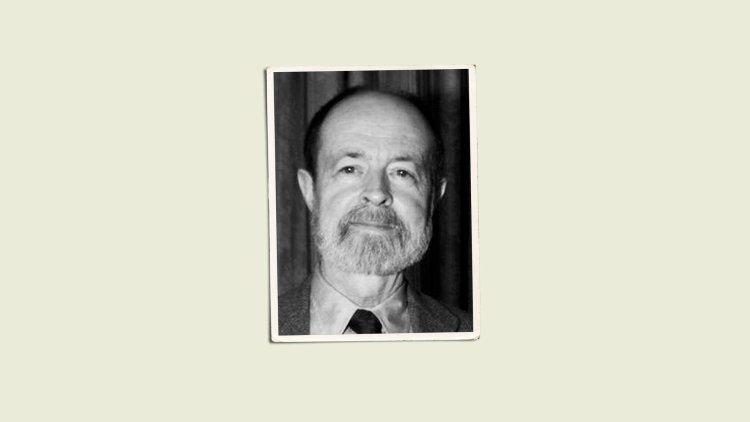

William Whitworth, the editor of The Atlantic from 1980 to 1999, had a soft voice and an Arkansas accent that 50 years of living in New York and New England never much eroded. It was as much a part of him as his love of jazz, his understated sartorial consistency, and his deep dismay when encountering the misuse of lie and lay, a battle he knew he had lost but continued to fight. Bill, who led this magazine during a period of creative evolution, died last week in Conway, Arkansas, near his hometown of Little Rock, at the age of 87. He is survived by his daughter, Katherine W. Stewart, and by a half brother, F. Brooks Whitworth.

Bill was a mentor to two generations of writers—writers of narrative reporting, primarily, but also novelists, biographers, intellectuals, essayists, and humorists. He expanded The Atlantic’s topical range and its cultural presence. His editorial instincts were penetrating, but couched in a manner that was calm and grounded. James Fallows, a longtime contributor who came to The Atlantic a few years before Bill arrived, was among the people we asked for their recollections. He remembers their initial meeting in a high-ceilinged office at 8 Arlington Street, in Boston, across from the Public Garden:

I saw a slight man, bearded, with receding hair, wearing a bow tie. “Mr. Fallows,” he said softly, “I’m Bill Whitworth.” Thus began an hour of his patiently asking me about how The Atlantic worked, and how much I was paid, and why I’d made this or that choice in the recent stories I’d done. Bill entirely directed our first conversation with seemingly simple questions: Did you think about this? Why did you write that? Can you explain what the experts are saying? What if they’re all wrong? Who did you want to talk with who got left out? What do you still need to know?

A reporter’s role in life boils down to going around and asking, “What is this?” and “How does it work?” Decades of working with Bill made his colleagues understand that an editor’s role in the final stage of an article boils down to asking, “What are you trying to say here?” and “Can we leave this part out?” In the conception stage of an article, the questions boil down to “What have you seen?” and “Why does it matter?”

I love knowing that the one book with Bill’s byline (as opposed to the dozens or hundreds he inspired, improved, or edited), published when he was 33, is called Naïve Questions About War and Peace. The book is the long transcript of a conversation—urged along by Bill’s faux-naïve questions—with one of the Vietnam War’s main defenders, Eugene V. Rostow. Rostow keeps giving Bill high theory as a rationale for the war. Bill keeps asking “What are you trying to say here?” and “Why does it matter?”

William Alvin Whitworth was born in Hot Springs, Arkansas, in 1937. He grew up in Little Rock, attended Central High School, received a B.A. from the University of Oklahoma, and then returned to Little Rock as a reporter for the Arkansas Gazette. Among the stories he covered was the fight over desegregation, centered on his old high school. At the Gazette, Bill met two people who became lifelong friends—Ernest Dumas and Charles Portis, later a novelist (Norwood, True Grit, The Dog of the South). In 1963, Bill followed Portis to Manhattan to take a job at the New York Herald Tribune, where his newsroom colleagues included Tom Wolfe, Jimmy Breslin, Dick Schaap, and the photographer Jill Krementz. On his second day at the Trib, John F. Kennedy was assassinated. During the years that followed, Bill covered John Lindsay’s New York City mayoral race, Robert F. Kennedy’s Senate race, the first Harlem riots, the free-speech movement at Berkeley, the Vietnam anti-war protests—he got tear-gassed a lot—and the Beatles’ first trip to the United States. He was in the Ed Sullivan Theater for their American-television debut.

Krementz showed some of Bill’s clips to her friend Brendan Gill, a staff writer and drama critic for The New Yorker, who in turn shared them with the magazine’s editor, William Shawn. One day Bill got a call from Shawn out of the blue, asking him to come by for a conversation. As Bill recalled in an oral history for the Pryor Center, at the University of Arkansas, “We had several mysterious meetings—mysterious to me, because it was never specified why we were talking.” Until finally Shawn offered him a job. He started at The New Yorker in 1966.

For the next seven years, he wrote full-time for the magazine, mainly features under the “Profiles” and “Reporter at Large” rubrics. A number of his articles from that time would live in the magazine Hall of Fame, if such a place existed—among them his profiles of the Theocratic Party’s recurring presidential candidate, Bishop Homer A. Tomlinson, and of the television-talk-show host Joe Franklin.

In the early 1970s, Bill began to spend less time writing and more time editing. Among his writers were the journalist and historian Frances FitzGerald, the film critic Pauline Kael, and the biographer Robert Caro, whose first book, The Power Broker, about Robert Moses, Bill excerpted for the magazine. In the late 1970s, Shawn began handing off some of his duties to Bill, who for several years served as his de facto deputy and heir apparent.

In 1980, the real-estate developer Mortimer B. Zuckerman bought The Atlantic, which had been flailing financially under its previous ownership. He offered the job of editor to Bill, who accepted it only after Zuckerman agreed that he would never meddle in editorial affairs—a promise that he kept. For his first issue as editor—April 1981—Bill featured a Philip Roth short story on the cover. The Whitworth-Roth friendship would last for decades, until Roth’s death, interrupted only for a few years in the 1990s when, after a scorching, two-sentence dismissal of one of his novels by The Atlantic’s book reviewer Phoebe-Lou Adams, Roth boxed up all his back issues of the magazine and mailed them to Bill, with a note saying that he would never speak to him again. And he didn’t, for a number of years. Then one day a postcard from Roth arrived in the mail. “Bill,” it read, “Let’s kiss and make up.”

One early coup for Whitworth’s Atlantic was an extensive excerpt—spread over several issues—from the first volume of Caro’s epic biography of Lyndon B. Johnson. Writers such as Seymour Hersh, V. S. Naipaul, and Garry Wills soon began to appear in the magazine. The December 1981 cover story—“The Education of David Stockman,” by William Greider, a news editor at The Washington Post—revealed that Ronald Reagan’s own budget director believed the new administration’s “supply side” economic program to be essentially specious. The article, based on lengthy conversations with Stockman, caused a furor. Over the years, Bill would publish work by Elijah Anderson, Saul Bellow, A. S. Byatt, Gregg Easterbrook, Louise Erdrich, Ian Frazier, Jane Jacobs, Robert D. Kaplan, George F. Kennan, Randall Kennedy, Tracy Kidder, William Langewiesche, Bobbie Ann Mason, Conor Cruise O’Brien, Barbara Dafoe Whitehead, E. O. Wilson, Gore Vidal, and many more. Crucially, the roster did not consist only of contributors who were already big names. The writer Holly Brubach recalls her own experience when she first sought to write for The Atlantic:

I was in my twenties, and, for reasons I found hard to fathom, Bill believed in me—this was long before I believed in myself. The handful of writers I’d encountered claimed that they’d always felt destined for a life dedicated to the making of literature, that they’d begun keeping a journal in childhood; they never seemed to doubt that their ideas were worthy of the reader’s attention. On that basis, I told Bill, I didn’t think I was a writer. He asked me if I trusted his judgment. Of course I did. “Then why don’t you just proceed on faith for a while?” he replied.

Another contributor, Benjamin Schwarz, describes his first encounter:

“Mr. Schwarz? This is Bill Whitworth, at The Atlantic.” So Bill introduced himself to me, a neophyte writer fumbling at a career shift, when we first spoke, in 1995. I’d sent Bill an unsolicited, provocative manuscript barely a week before, and he was calling to tell me he’d like to run it as the cover story. That was all Bill: open toward an unknown writer, confident in his judgment, impervious to reputation and approved opinion.

He was eager to publish points of view he did not agree with, so long as they adhered to certain standards of rigor, and to publish articles that he may not have cared for stylistically, noting that homogeneity of taste soon makes any publication feel stale. Nicholas Lemann, an Atlantic contributor during most of the Whitworth years, described a quality in writing that Bill always looked for:

When I went to work for him, I had a strong impulse to become a Gay Talese–style “literary journalist,” and he cured me of that. He insisted that a piece, or at least a major piece, have a strong and original point to make, whatever its virtues were as a piece of writing. And he was completely, uncannily immune to whatever the liberal/media conventional take of the moment was. You had to say something that the rest of the world was not also saying. That has really stayed with me—I try to put the work that I do to Bill’s test every day.

With the art director Judy Garlan, Bill also made The Atlantic a showcase for art and graphic design, something that it had never been. Work by Edward Sorel, Seymour Chwast, Guy Billout, and István Bányai, among others, appeared regularly in its pages. The Atlantic began to win awards for its design, not just its journalism.

During the two decades of Whitworth’s tenure as editor, The Atlantic was a finalist for dozens of National Magazine Awards and the winner of nine. Bill didn’t especially relish the compliments that began to pour in, about how he had revived the “once staid” Atlantic. He had gone back to look, he would explain, and his three immediate predecessors had deservedly won similar accolades. It made you wonder, he said, when the magazine could have actually been in that staid condition. In any case, he guessed, his own years on the job would one day become the staid foil to some successor’s resuscitation—and fine with him. As long as this kept happening with every handover, it was good news for the magazine.

Writers remember Bill’s conversations about articles as shrewd, gentle, and patient. His comments on galley proofs, meant for a writer’s editor alone, were more direct, sometimes requiring diplomatic translation before being passed along. He wrote in pencil in a tiny but perfect script, a sort of 20th-century Carolingian minuscule of his own devising. There was something sacramental about the way he worked: a single lamp illuminating a Thomas Moser desk, a galley before him on a brown blotter, retractable pencil in hand, jacket off, bow tie secure, door ajar.

He had a reverence for editorial comments on galleys, and to illustrate some technical point once pulled from a file drawer a galley of an article by A. J. Liebling covered with marginal comments by William Shawn. His own comments ranged from small corrections to magisterial anathemas to unexpected excursions into questions of culture and journalism. Encountering a usage that he simply would not allow—and there were many, such as using verbs like quipped and chortled; and using convinced when you meant persuaded; and using human as a noun, instead of human being—he would circle it and write in the margin, “Let’s don’t.” References to “the average American” were banned, on the grounds that there is no such thing. A writer once began a sentence with the phrase “Taking a deep breath that rounded out her cheeks like a trumpet player’s …” Bill noted the impossibility of that feat of inhalation with the words “Try it.” Another writer wanted to use his nickname as a byline. Bill circled the “Jeff” and wrote, “Ernie Hemingway, Bob Penn Warren, Bill Faulkner, and Jim Joyce all advise against this.” As he read galleys, a word or phrase sometimes jogged a memory and led to a ballooning comment in the margin, just for the record. A mention of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood prompted a note recounting a conversation in which Shawn expressed to Bill some of his misgivings about Capote’s work.

When Bill liked an article, his praise was genuine but spare. He didn’t gush, telling writers that their work was “extraordinary” or “magnificent.” He preferred simple words with durable meanings. The apogee of his joyful reaction was a penciled “Good piece” on the last page of a galley, words that editors sometimes cut out and sent to the writer in question. One editor, visiting a writer at home, found the words framed and hanging on an office wall.

“Bill expressed himself best on paper,” recalls Corby Kummer, who joined The Atlantic staff as a young editor in the early 1980s.

In his notes on galley proofs of articles, each a master class in editing, he was intimate, playful, patient, impassioned. In person, a very slow burn. At our first meeting, in a midtown Manhattan Italian restaurant—he particularly favored Italian restaurants, I came to learn—I said, by way of starting a conversation, “This is a very business-lunch kind of a place.” Bill looked at me and said, “Well, this is a business lunch,” letting a silence fall. During the main course, he asked me what were some of my favorite books and authors. It was my turn to look at him. Had I ever, in fact, actually read a book? I was fairly sure I had, but could think of not one author or one title. Finally he described his enthusiasm for George Orwell, and I recalled that yes, I had read and admired Down and Out in Paris and London. It was The Road to Wigan Pier he found exemplary, though. Naturally, I bought it the next day.

A major innovation that Bill brought to The Atlantic was a fact-checking department. At this magazine as at most others, checking facts had mainly been the domain of copy editors, who looked up names and dates in reference books. Too often, Bill would say, publications by default depended on a single tried-and-true way of discovering whether something was wrong: “by publishing it.” Bill was shaped by his experience at The New Yorker, where fact-checking had been intensive for decades. A checking department has been part of The Atlantic’s DNA ever since. His attitude toward its importance is hard to overstate. Once, on a galley proof, he reacted to a writer’s statement that the sanctity of facts wasn’t much, but was all we had: “I can’t agree that the sanctity of facts isn’t much. After Hitler, after the Moscow show trials and the other horrors of this century, facts are precious. In one sense (science) they are the very essence of Western civilization.” He paused, then continued with his pencil on a new line: “On the other hand, the sanctity of facts isn’t all we have. We also have kindness, decency, children, Bach, Beethoven, etc.”

Yvonne Rolzhausen, currently the head of The Atlantic’s fact-checking department, recalls having Bill by her side during one especially difficult episode:

I had just started as a fact checker and was working on what was meant to be a lighter feature on the popularity of plastic surgery. We quickly realized that it was, instead, a contentious takedown of risky procedures and the surgeons performing them. As the publication deadline approached, I had harrowing phone calls with a screaming (and litigious) practitioner. Bill spent many an hour walking through the piece with me to see how I was doing. We’d sit at his desk, and he’d offer me vanilla sandwich cookies as I described the latest threats. We delayed the piece twice while I worked away on it, but I’ll always be grateful for Bill’s calm demeanor and support.

Another innovation that Bill brought to The Atlantic—and that is no longer part of its character—was a policy of not holding editorial meetings. He preferred one-on-one engagements with his editors. Like anyone, Bill had his quirks, and maybe that was one of them. When taking a writer or an editor to lunch, he insisted on sitting side by side at the restaurant, rather than across a table. (He used the same side-by-side configuration when meeting with writers in his office, sitting alongside the author in an easy chair.) His framed memorabilia—including the original Bernard Fuchs drawing of Bishop Tomlinson, for that 1966 profile—leaned haphazardly against a wall, never hung in 20 years. Bill read widely about vitamins and other supplements, his beliefs venturing at times into speculative territory, a pharmacological Area 51; if you’d been out with the flu, you might return to find pamphlets on your desk. He liked pigs, and published a fond and funny article about them in 1971 that endures as a small classic. He would order catfish whenever he saw it on a menu in the Northeast, but seemingly only to confirm that it didn’t measure up to the bottom-feeding creatures found in Arkansas.

Bill was particular about his deportment. He was once discovered at his desk with a tailor’s tape, measuring the collar of a blue button-down shirt. He was convinced—not persuaded but convinced—that Brooks Brothers, in a misguided bid for modishness, had slightly extended the point of the collar, resulting in a modest outward bulge when the collar was buttoned down. Bill described the result as a “midwestern roll,” as if this were an age-old term of art. He used that term in his months-long correspondence with Brooks Brothers executives and with Alan Flusser, the author of Clothes and the Man: The Principles of Fine Men’s Dress, whom Bill sought to enlist as an expert witness.

His knowledge of jazz was profound. He had learned to play the trumpet at a young age, and at the University of Oklahoma he’d had a band called the Bill Whitworth Orchestra. When he went to work at the Gazette, it meant spurning approaches from the Jimmy Dorsey and Stan Kenton bands. As a young reporter, he had invited the trumpeter and band leader Dizzy Gillespie, whom he’d met at a performance in St. Louis, to come to Little Rock. Gillespie did, and stayed with Bill and his mother. They remained friends. As Gillespie recalled later in a New Yorker article, Bill wrote to him after the Little Rock visit to say that brass players from all over had come to his home to “kiss the sheets.” Bill’s taste in decor might run to beige walls and Shaker minimalism, but music for him was pure color. Terry Gross, the Fresh Air host, recalls that Bill would email about interstitial music on the show that he enjoyed but couldn’t identify. (“He also urged me to maximize my intake of Vitamin D, and start taking Vitamin K, which I didn’t even know existed.”) To be invited to “listen to some music” at his home wasn’t a casual experience—it wasn’t drinks, small talk, and something playing in the background. You sat next to him in a high-backed chair against an off-white wall, facing speakers that stood against the unadorned opposite wall. From time to time, after some inspired solo, he might turn his head to you briefly and nod.

In 1999, Mort Zuckerman sold The Atlantic to David Bradley, and Michael Kelly took over as editor. The magazine would eventually move to Washington, and Bill himself would eventually move back to Little Rock, where he enjoyed a close circle of friends. He did not retire. For some years he edited articles for The American Scholar. Rickety stacks of book manuscripts that he was editing for publishers rose from the floor of his home. The books ranged from weighty historical tomes to the acclaimed memoirs (in two volumes) of Anjelica Huston. Anne Fadiman, a former editor of The American Scholar, paints a familiar portrait of Bill at work:

When the author of a piece about which he was particularly unenthusiastic used the verb “impress” without a direct object, Bill wrote in the margin, “This maddening use of transitive verbs as intransitive is a sort of literary fungus spread by reviewers and critics.” Next to the observation that beaks enabled early birds to catch their worms, he wrote, “Hmmm. Does this work out? All birds are enabled by their beaks. Early birds enabled by their earliness.” And below a simile he judged unnecessary, he wrote, “Look, Ma! I’m writing!”

Colleagues and friends regularly made trips to Little Rock and spent a day or two. There would be dinner with Arkansas friends. Some music. Some real catfish. And Bill was available for advice from afar, editing the work of writers he admired. Holly Brubach, in recent years at work on a biography, would send Bill each chapter as she finished it, and then they’d talk for hours by phone:

Occasionally, over the course of these marathon phone sessions, we would stray from the paragraph at hand and retrieve some small experience that had lodged itself in one of our memories, and I relished those interruptions, as if we’d stopped for a picnic by the side of the road. Bill would offer a glimpse of the young man he’d been before occupying the pedestal on which I and so many others had placed him. One of these stories, prior to his career in journalism back east, involved being a young pickup musician in Little Rock, where he and a friend had landed a gig playing for Mitzi Gaynor, in town with her own show. She had nice legs. After rehearsal, he’d knocked on her dressing-room door. “Oh, hello,” she greeted him, “you’re the guy on trumpet,” before politely declining whatever it was he was proposing. “You see that man over there?” she asked. “He’s my manager, and he’s also my husband, and if I were to accept your invitation, he would kill us both.” Bill was of course gracious in the face of rejection. She shook her head, and, as he walked away, he heard her say to no one in particular, “It’s always the saxophonists and the trumpeters.”

What's Your Reaction?