Why Biden’s Pro-worker Stance Isn’t Working

The most pro-labor president in history could hardly do more for unions, but their members aren’t feeling it.

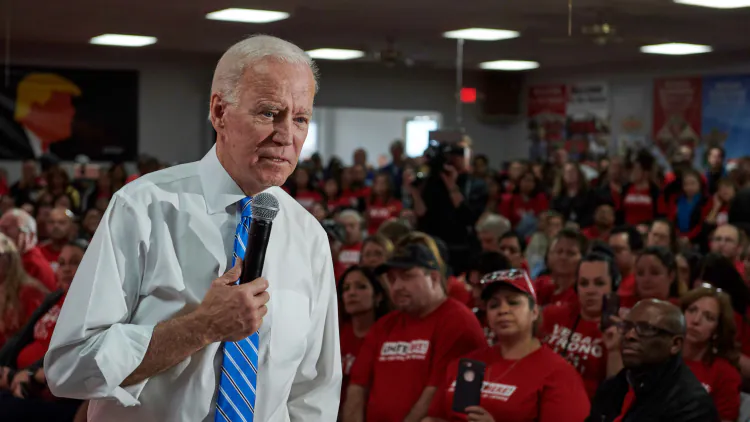

Joe Biden courted the leaders of the Teamsters this week, looking for the endorsement of the 1.3-million-member union. He will probably get it. The Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank, calls him “the most pro-union president in history.” He’s already won the endorsement of many of the country’s most important unions, including the United Auto Workers, the AFSCME public employees’ union, the Service Employees International Union, and the main umbrella organization, the AFL-CIO.

Biden’s real concern in November, though, isn’t getting the support of union leaders; it’s winning the support of union members. Labor’s rank and file were a valuable part of his winning coalition in 2020, when, according to AP VoteCast, he got 56 percent of the union vote. Today, things on this front are looking a little shakier, particularly in key electoral battlegrounds. A New York Times/Siena survey of swing states late last year, for instance, found that Biden was tied with Donald Trump among union voters (who, that same survey noted, had voted for Biden by an eight-point margin in the previous general election).

That slippage is not itself a reason for Democratic panic, because it suggests that the drop-off in union support has been similar to the decline in support for Biden generally. But the softening support among union voters is striking in light of how hard Biden has tried to win their trust. He has certainly shown his love for workers during his three-plus years in office, but not even unionized workers seem to love him back.

[Read: Is Biden the most pro-union president in history?]

Biden has made plenty of symbolic and rhetorical gestures, including the exclusion of Tesla CEO Elon Musk from a 2021 electric-vehicle summit at the White House, most likely because of Musk’s anti-union stance, and walking a UAW picket line during the union’s strike against the Big Three carmakers last fall. He’s made support for labor, and the working class generally, a legislative priority, pushing bills that subsidize investments in infrastructure and manufacturing, protect union pension funds, fund apprenticeships, and boost wages for federal contractors. He also kept Trump’s trade tariffs, which industrial unions mostly favored, in place. And the people he appointed to the National Labor Relations Board have handed down a series of rulings that have made it easier for workers to organize and harder for employers to punish them for doing so. To give just one metric (from the Center for American Progress), the NLRB ordered companies to hire back more illegally fired workers in Biden’s first year than it did during Trump’s entire four years in office.

Biden has done all of this at a time when unions are enjoying a big surge in popularity. Fifteen years ago, public support for unions, as measured by Gallup, dipped below 50 percent for the first time since it was first surveyed, in the 1930s. Today, more than two-thirds of Americans say they support unions, one of the highest marks since the ’60s, and polling found that two-thirds to three-quarters of Americans supported the recent strikes by the UAW and by Hollywood screenwriters and actors, which not only enjoyed a high profile but were also successful. Perhaps this means that Biden would be doing even worse in the polls if he hadn’t been so pro-labor. But so far, the political rewards seem to have been meager at best.

[James Surowiecki: The Big Three’s inevitable collision with the UAW]

Some of this can be explained straightforwardly by the fact that the same issues dragging down Biden’s popularity among voters generally, such as inflation and immigration, also hurt him with union voters. That seems particularly true for white men working in old-line industries, a segment of workers who were already disposed to support Trump. (According to a Center for American Progress Action Fund study, white male non-college-educated union workers supported Trump over Biden by 27 points in 2020, though Biden did nine points better with them than he did with white male non-college non-union workers.)

On top of this, the percentage of American workers in unions has not risen over the past three years—only about 10 percent of all workers are unionized, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and in the private sector, that proportion falls below 7 percent (despite some high-profile organizing campaigns such as the one at Starbucks). So even though the public has become more supportive of labor organizations, union issues simply have less cultural and political resonance than they once did. And unions themselves are less integral to their members’ daily lives than they once were, particularly in former industrial strongholds that are now swing states, as the Harvard scholars Lainey Newman and Theda Skocpol document in their recent book, Rust Belt Union Blues. That means it takes more work to reach union voters and win their support; endorsements from leaders alone won’t deliver workers’ votes.

Another dimension of Biden’s limited success is that he faces an opponent in Trump who, unlike most Republican presidential candidates, has also courted union voters aggressively while selling himself as a tribune of the working class. That stand is mostly marketing: During Trump’s presidency, the NLRB was actively hostile to union organizing efforts, and when House Democrats passed a bill that would make joining unions easier for workers and significantly weaken states’ right-to-work laws, the Trump White House threatened to veto it. (The president never got the chance; the bill did not come up for a vote in the Senate.) But Trump’s rhetorical nods toward labor have helped blur the contrast between him and Biden. And the fact that Trump’s signature economic issue is raising tariffs has also helped him with union voters.

[David A. Graham: Why isn’t Trump helping the autoworkers?]

What that suggests, of course, is that Biden needs to do a better job of sharpening that contrast on labor policy. But that’s not as easy as it sounds. Much of the struggle over workers’ rights and interests today takes place in a courtroom or through administrative hearings or via regulatory changes. This sort of bureaucratic haggling means that it’s hard to make labor issues vivid for voters—even union voters. For all the difference in the NLRB’s record during the Biden administration compared with that under Trump, administrative-agency rulings are not the stuff of a rousing stump speech.

These problems are not insurmountable—and the unions themselves will be trying to help Biden surmount them. (The Service Employees International Union, for instance, just announced that it would be spending $200 million on voter education in this election cycle.) And once the presidential campaign gets fully under way, union voters may well move back in Biden’s direction. But Biden’s difficulty in landing their support is a microcosm of his struggles with voters broadly: The way they feel about him seems disconnected from what he’s done.

What's Your Reaction?