Trump’s Latin American Gamble

He may get his mass deportations—and a world of instability in Latin America.

For a moment on Sunday, the government of Colombia’s Gustavo Petro looked like it might be the first in Latin America to take a meaningful stand against President Donald Trump’s mass-deportation plans. Instead, Petro gave Trump the perfect opportunity to show how far he would go to enforce compliance. Latin American leaders came out worse off.

On Sunday afternoon, Petro, a leftist who has held office since 2022, announced on X that he would not allow two U.S. military aircraft carrying Colombian deportees to land. He forced them to turn back mid-flight and demanded that Trump establish a protocol for treating deportees with dignity.

Colombia had quietly accepted military deportation flights before Trump’s inauguration, according to the Financial Times. But the Trump administration began flaunting these flights publicly, and some deportees sent to Brazil claimed that they were shackled, denied water, and beaten. Petro saw all of this as a step too far, and reacted. He clarified that he would still accept deportations carried out via “civilian aircraft,” without treating migrants “like criminals” (more than 120 such flights landed in Colombia last year).

Trump responded by threatening to impose 25 percent tariffs on all Colombian goods (to be raised to 50 percent within a week), impose emergency banking sanctions, and bar entry to all Colombian-government officials and even their “allies.” The message was clear: To get his way on deportations, he would stop at nothing, even if this meant blowing up relations with one of the United States’ closest Latin American partners.

[Quico Toro: Trump’s Colombia spat is a gift to China]

Petro almost immediately backed down. He seemed to have taken the stand on a whim, possibly in part to distract from a flare-up in violence among armed criminal groups inside his country. The White House announced that Colombia had agreed to accept deportation flights, including on military aircraft. Petro gave a tepid repost, then deleted it.

For Trump, the incident was a perfect PR stunt, allowing him to showcase the maximum-pressure strategy he might use against any Latin American government that openly challenges his mass-deportation plans and offering a test case for whether tariffs can work to coerce cooperation from U.S. allies. For Latin America, the ordeal could not have come at a worse time.

Across the region, leaders are bracing for the impact of deportations—not only of their own citizens, but of “third-country nationals” such as Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, and Cubans, whose governments often refuse to take them back. They are rightfully worried about what a sudden influx of newcomers and a decline in remittance payments from the United States will mean for their generally slow-growing economies, weak formal labor markets, and strained social services, not to mention public safety, given the tendency of criminal gangs to kidnap and forcibly recruit vulnerable recent deportees.

If Latin American governments are trying to negotiate the scope or scale of deportation behind closed doors, they do not appear to be having much success. Several leaders seem to be losing their nerve. Mexico’s president, Claudia Sheinbaum, went from expressing hope for an agreement with the Trump administration to receive only Mexicans to accepting the continued deportation of noncitizens—perhaps because Trump threatened to place 25 percent tariffs on all Mexican goods as soon as February 1. Honduras threatened to expel a U.S. Air Force base on January 3 if the United States carried on with its deportation plans. By January 27, Honduras folded, saying that it would accept military deportation flights but requesting that deportees not be shackled. Guatemala is trying to draw the line at taking in only fellow Central Americans.

Most Latin American leaders will bend to Trump’s wishes on mass deportation rather than invite the strong-arm tactics he threatened to use on Colombia. One reason is that tariffs can really hurt the countries whose cooperation Trump needs most on deportations. Unlike most of South America, Mexico, Colombia, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador still trade more with the United States than with China. Only with Mexico, the United States’ largest trade partner, does the leverage go both ways, but even there it is sharply asymmetrical (more than 80 percent of Mexican exports go to the U.S., accounting for nearly a fifth of the country’s GDP).

Latin American countries could improve their bargaining position by taking a unified stand and negotiating with Trump as a bloc. But the chances that they will do so are slim and getting slimmer. Today, Honduran President Xiomara Castro called off a planned meeting of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, a left-leaning regional bloc, to discuss migration, faulting a “lack of consensus.”

[Juliette Kayyem: The border got quieter, so Trump had to act]

Latin American presidents have relatively weak incentives to fight Trump on migration. The region is home to more than 20 million displaced people, millions of whom reside as migrants or refugees in Mexico, Colombia, Peru, and elsewhere—and yet, migration is simply not that big of a diplomatic political issue in most countries. That could change if deportations reach a scale sufficient to rattle economies, but Latin American leaders are focused on the short term, much as Trump is. Presidential approval ratings tend to rise and fall based on crime and the economy more than immigration, and at least for now, anti-U.S. nationalism is not the political force it has been in the past.

So Trump will likely get his way in more cases than not. But he shouldn’t celebrate just yet, because the short-term payoff of strong-arming Latin America will come at the long-term cost of accelerating the region’s shift toward China and increasing its instability. The latter tends, sooner or later, to boomerang back into the United States.

“Every South American leader, even pro-American ones, will look at Trump’s strategy vis-à-vis Panama, Colombia, and Mexico and understand the risks of being overly dependent on the U.S. right now. The majority will seek to diversify their partnerships to limit their exposure to Trump,” Oliver Stuenkel, a Brazilian international-relations analyst, posted on X in the middle of the Colombia standoff. He’s right. Latin American leaders, even several conservative ones, moved closer to China during Trump’s first term, which is not what Trump wants. Reducing China’s presence in Latin America seems to be his No. 2 priority in the region (see his threats to Panama over the Hong Kong company operating near its canal). Chinese investments in dual-use infrastructure and 5G technology pose long-term national-security risks to the United States. But Trump’s tariff threats and coercion could rattle Latin America and help China make its sales pitch to the region: We’re the reliable ones. The long-standing lament that Latin American conservatives, centrists, and leftists share is that whereas the United States comes to the region to punish and lecture, China comes to trade. Trump’s current approach gives that complaint extra credence.

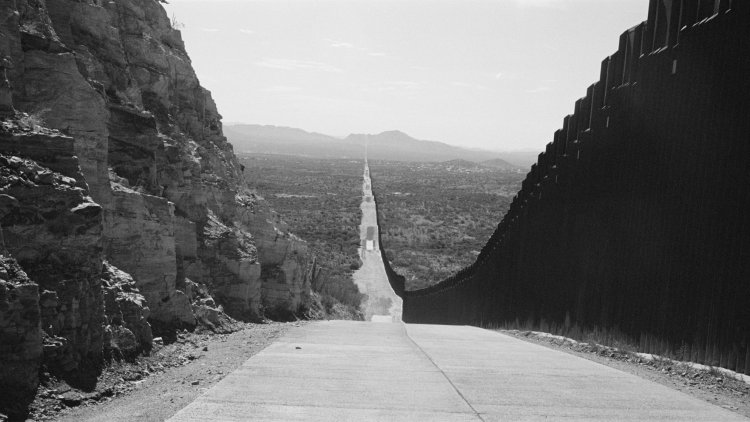

[From the September 2024 issue: Seventy miles in hell]

Trump’s deportation plans threaten to destabilize parts of Latin America, which will have repercussions for the United States. The arrival of hundreds of thousands of people to countries without the economic or logistical capacity to absorb them could leave the region reeling. Consider that the Trump administration is negotiating an asylum agreement with El Salvador—a country with one of the weakest and smallest economies, and highest rates of labor informality, in all of Central America. If Venezuelans, Nicaraguans, and Cubans are sent there, they are almost guaranteed not to find jobs. People deported to Honduras and Guatemala will also likely struggle to find work and face recruitment by gangs. And because remittances make up about a fifth of GDP in Guatemala and about a quarter in El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua, large-scale deportations threaten to deliver a brutal shock to their economies. Mexico’s economy is bigger and sturdier, but economists have shown that large influxes of deportees there, too, tend to depress formal-sector wages and increase crime. The inflow of workers might still benefit economies like Mexico’s in the long run. But in the short to medium term, Trump’s mass-deportation plans are a recipe for instability.

The lesson of the past several decades—Trump’s first term included—is that Latin American instability never remains contained within the region. It inevitably comes boomeranging back to the United States. Mexican cartels didn’t gain far-reaching influence just in their country. They fueled a fentanyl epidemic that has killed more than a quarter million Americans since 2018. Venezuela’s economic collapse under authoritarian rule didn’t bring misery only upon that country; it produced one of the world’s biggest refugee crises, with more than half a million Venezuelans fleeing to the United States. Instability nowhere else in the world affects the United States more directly, or profoundly, than that in Latin America.

In the 1980s and ’90s, internal armed conflicts raged in Colombia and Central America, and Mexico confronted serial economic crises. Since then, the United States’ immediate neighbors have become relatively more stable, democratic, and prosperous. But slow growth, fiscal imbalances, and, above all, the growing power of organized crime have tested that stability in recent years. Trump is adding to the pressure with mass deportations—then hoping to contain whatever erupts by simply hardening the southern border. That’s quite the gamble.

What's Your Reaction?