Total Eclipses Are a Cosmic Accident

Anyone who watches the moon glide over the sun on April 8 will be witnessing the planetary version of a lightning strike.

Eclipses are not particularly rare in the universe. One occurs every time a planet, its orbiting moon, and its sun line up. Nearly every planet has a sun, and astronomers have reason to believe that many of them have moons, so shadows are bound to be cast on one world or another as the years pass.

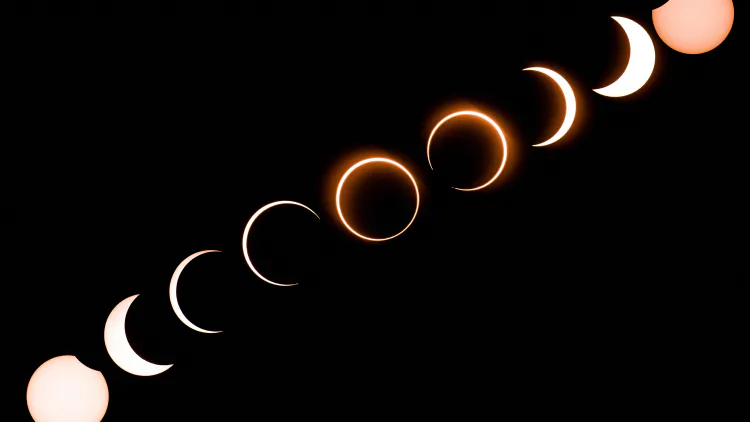

But solar eclipses like the one that millions of Americans will watch on April 8—in which a blood-red ring and shimmering corona emerge to surround a blackened sun—are a cosmic fluke. They’re an unlikely confluence of time, space, and planetary dynamics, the result of chance events that happened billions of years ago. And, as far as we know, Earth’s magnificent eclipses are unique in their frequency, an extraordinary case of habitual stellar spectacle. On April 8, anyone who watches in wonder as the moon silently glides over the sun will be witnessing the planetary version of a lightning strike.

Seen from a planet, a solar eclipse can vary in nearly infinite ways. Everything depends on the apparent size of the star and the planet’s orbiting body. Some eclipses, known as annular eclipses or transits, appear as nothing more than a small black dot crossing the solar disk. They occur when a moon looks much smaller than the sun in the sky, whether that’s because it is especially small or especially distant (or the star is especially large or close). Mars, for example, has two wee, potato-shaped moons, each too small to block out the sun.

[Read: What would the solar eclipse look like from the moon?]

By contrast, if a moon appears much bigger in the sky than the sun, an eclipse would see the tiny solar disk entirely blotted out by the far larger moon, as is the case with many of Jupiter’s and Saturn’s biggest moons. Such an eclipse would mean a shocking change from light to darkness for sure, but hardly the celestial drama that’s seen on Earth. The eerily perfect replacement of our sun’s disk by an equal-size black orb, followed by the startling appearance of previously invisible and dramatic regions of illumination surrounding it—that kind of eclipse demands very particular conditions.

Our sun, like all stars, is a giant ball of superheated plasma. Close to its surface, giant fiery flares called prominences blast upward; beyond them extends the corona, the sun’s outer atmosphere, which can measure in the millions of degrees on any temperature scale. Normally, we can’t see either of these details because the sun itself is simply too bright. But during a total solar eclipse, we can: The prominences form an irregular ring of deep red just surrounding the sun, with the corona shimmering beyond them. That’s because our moon appears to be almost exactly the same size as the sun from our vantage point on Earth’s surface—big enough to block most of its light, but not so big that it blots out the sun’s outer layers.

Relative to the diameter of the Earth, our moon is unusually big for a satellite, at least in our solar system. If you were an alien astronomer visiting our corner of space, you’d probably think the Earth-moon system was two planets orbiting each other. And yet, rotund as it may be, our moon is still 400 times smaller in diameter than the sun—but it also just so happens to be roughly 400 times closer to Earth. And even that coincidence of space and size is, in truth, an accident of time. Today, the moon orbits about 240,000 miles from Earth. But 4.5 billion years ago, when it was first born from an apocalyptic collision between Earth and a Mars-size planet, it was only 14,000 or so miles away, and therefore would have looked about 17 times bigger in the sky than it does today. Since then, the moon has been slowly drifting away from Earth; currently, it’s moving at about 1.5 inches a year. As the size of its orbit increased, its apparent size in Earth’s sky decreased. That means the eclipses we see today were likely not possible until about 1 billion years ago, and will no longer be possible 1 billion years from now. Humanity has the luck of living in the brief cosmic window of stunning eclipses.

[Read: The moon is leaving us]

Not every eclipse that’s visible from Earth offers perfect views of the prominences and corona while also throwing the world into temporary night. The slightly noncircular shape of the moon’s orbit means that it grows and shrinks in the sky. But near-perfect total eclipses account for about 27 percent of all sun-moon overlaps on Earth—often enough that they can be spotted by someone in any given region every generation or so. In contrast, eclipses on the other planets in our solar system are almost always either too small to cover the sun or so large that the ring of fire and corona are hidden. Perfect total eclipses are rare jewels for our neighbors, but common for us.

That special frequency has allowed eclipses to leave deep imprints in human myth and history. Total eclipses on Earth can last as little as a few seconds and as long as seven minutes, but for our ancestors, these brief moments were still descents into terror. “A great fear taketh them” reads an Aztec description of the public reaction to an eclipse. “The women weep aloud. And the men cry out … eternal darkness will fall, and the demons will come down.” One legend holds that, thousands of years ago, a Chinese emperor ordered the execution of two court astronomers who failed to predict an eclipse.

Eclipses were dramatic enough that they helped push our forebears, such as the residents of Babylon and China in the millennia before the Common Era, to pay close attention to the sky. They drove kings and emperors to provide the resources that priests needed to make and keep long-term astronomical records. They helped spark the invention of methods for tracking the motion of celestial objects over lifetimes, and in this way the clockwork of the heavens was first revealed. In that long process of observation and recordkeeping, something else happened too: Eclipses helped compel humans to both develop and reveal our inmost capacity for a new and precise kind of reasoning that could be applied to the world.

[Read: Civilization owes its existence to the moon]

I believe that the cosmic accident of Earth’s perfect eclipses—with their high drama and hidden patterns, the panic they ignited in market squares, the danger they posed to those in power, the awe they inspired among the early priest-astronomers—may have served as a force driving humans to nothing less than science itself. And in building science, we gained the capacity to reshape the planet and ourselves. All of it might never have happened without the moon and sun appearing to be almost the same size from Earth. The lucky circumstances of our sky may well have been the gift that allowed us, eventually, to become its intimate.

What's Your Reaction?