The Harlem Renaissance Was Bigger Than Harlem

How Black artists made modernism their own

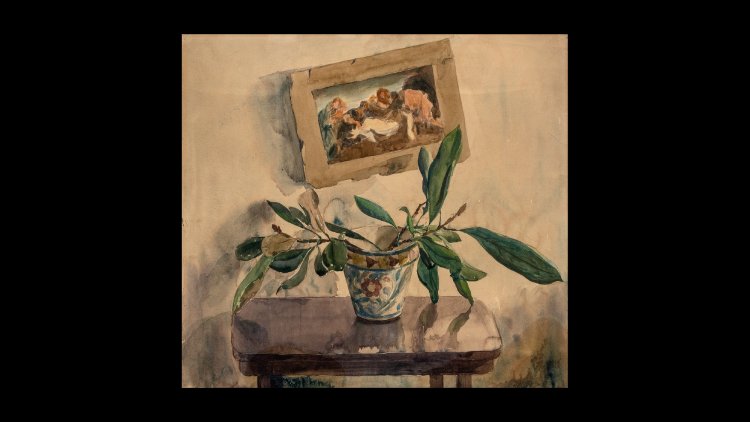

Sometimes it’s the sleepers that stay with you. In “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism,” a sprawling exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, it was a watercolor still life by Aaron Douglas. Born in Topeka, Kansas, in 1899, Douglas may be the most recognizable Black artist of the 1920s and ’30s. His appealing blend of Art Deco and African American affirmation enlivened books, magazines, and public spaces in his heyday, and paintings such as his grand Works Progress Administration cycle, Aspects of Negro Life, at the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library (now part of the Schomburg Center), have kept him visible ever since.

The watercolor, though, feels a world apart from his luminous silhouettes and vivid storylines. It houses no heroic figure pointing toward the future, no shackles being cast off. Instead we get leafy branches splaying out from a pot beneath a tattered picture hung askew on a wall. The branches might be magnolia—it’s hard to tell—but art nerds can recognize the crooked picture-within-a-picture as a loose rendering of Titian’s The Entombment of Christ (circa 1520), which has been in the Louvre for centuries. Turner copied it there in 1802, Delacroix around 1820, Cézanne in the 1860s. Douglas would have seen it when he was studying in Paris in the early 1930s.

The Titian might have attracted his attention for many reasons—its display of crushing grief and unvoiced faith, its sublimely controlled composition, or the warm brown skin that Titian gave the man lifting Christ’s head and shoulders, usually identified as Nicodemus. The Titian connection is not highlighted at the Met, but in its own oblique way, Douglas’s watercolor encapsulates the most important lesson this show has to offer: Art’s relationship to the world is always more complicated than you think.

Organized by Denise Murrell, who, as the Met’s first curator at large, oversees projects that cross geographical and chronological boundaries, this exhibition has a lot on its to-do list. It wants to remind us of Harlem’s role as a cultural catalyst in the early 20th century, while showing that those creative energies extended far beyond the familiar reading list of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, beyond literature and music, beyond the prewar decades, and beyond Upper Manhattan. It wants us to understand that Black American artists were learning from European modernists, and that European modernists were aware of Black contributions to world culture.

The exhibit showcases an abundance of mostly Black, mostly American painters and sculptors, as well as pictures of Black subjects by white Europeans, documentary photographs, film clips of nightclub acts, and objects by artists of the African diaspora working in locations from the Caribbean to the United Kingdom. Like an exploding party streamer, it unfurls in multiple directions from a starting point small enough to hold in your hand—in this case, the March 1925 special issue of the social-work journal Survey Graphic, its cover emblazoned with “Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro,” heralding a new cultural phenomenon.

That issue, edited by the philosopher Alain Locke, contained sociological and historical articles by Black academics along with poetry by the likes of Hughes and Jean Toomer. James Weldon Johnson, the executive secretary of the NAACP, offered an essay on the real-estate machinations that had made Harlem Black, and W. E. B. Du Bois contributed a parable highlighting the Black origins of American achievements in domains including the arts and engineering. The German-immigrant artist Winold Reiss provided eloquent portraits of celebrities such as the singer and activist Paul Robeson, along with those of various Harlem residents identified by social role in the manner of August Sander photographs—a pair of young, earnest Public School Teachers with Phi Beta Kappa keys dangling around their necks, a somber-faced Woman Lawyer, a dapper College Lad. All of this made manifest the galvanizing assumption that what Black Americans possessed was not a culture that had failed to be white, but one rich with its own inheritances and inventions; its own brilliance, flaws, and challenges. And Harlem was its city on a hill.

Working as an art teacher in Kansas City, Missouri, Aaron Douglas saw Survey Graphic and moved to New York, where he worked with Reiss and was mentored by Du Bois. When Locke expanded the Survey Graphic issue to book length (his pivotal anthology, The New Negro: An Interpretation), Douglas provided illustrations.

Locke and Du Bois were the intellectual stars of Black modernity, and they believed in the power of the arts to transform social perception. But where Du Bois once said, “I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda,” Locke was intrigued by the indirect but ineluctable workings of aesthetics. A serious collector of African art, he saw its severe stylizations and habits of restraint as a flavor of classicism, as disciplined in its way as Archaic Greek art, and hoped it might provide “a mine of fresh motifs ” and “a lesson in simplicity and originality of expression” to Black Americans.

Locke also took note of how European artists, bored with the verisimilitude, rational space, and propriety of their own tradition, had become smitten with Africa: how Picasso claimed the faceted planes of African masks as the starting point of cubism; how German expressionists enlisted the emphatic angularity of African carvings in their pursuit of emotional presence. They might be woefully (or willfully) ignorant of African objects’ original contexts and meanings, but, as Locke recognized, an important bridge had been crossed. Something definitively Black was inspiring the foremost white artists in the world.

No artist fulfilled the twin mandates of clear messaging and savvy, African-influenced modernism more successfully than Douglas. The style he developed took tips from the easy-to-read action of ancient-Egyptian profiles, the staccato geometries of African art, and the flat pictorial space of abstraction, and he put that style to work in narrative pictures designed to inspire hope, pride, and a sense of belonging to something larger than oneself. Du Bois might have called it propaganda, but under the name “history painting,” this kind of thing had constituted the most prestigious domain of pre-20th-century art. Think of Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii (1784), Emanuel Leutze’s Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851), and John Martin’s cast-of-thousands blockbusters like The Destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum (1822).

Let My People Go (circa 1935–39) is one of several majestic Douglas paintings included at the Met. Its design began as a tightly composed black-and-white illustration for James Weldon Johnson’s 1927 book, God’s Trombones: Seven Negro Sermons in Verse (in addition to running the NAACP, Johnson was a poet). Even within the more expansive space of the color painting, Let My People Go has a lot going on: Lightning bolts rain down from the upper right; spears poke up from the lower left as Pharaoh’s army charges in, heedless of the great wave rising like a curlicue cowlick at center stage. Slicing diagonally across all of this action, a golden beam of light comes to rest on a kneeling figure, arms spread in supplication. It’s a John Martin biblical epic stripped of Victorian froufrou, a modernist geometric composition with a moral.

Ambitious Black artists hardly needed Locke to point them toward Europe. “Where else but to Paris,” Douglas wrote, “would the artist go who wished really to learn his craft and eventually succeed in the art of painting?” Paris had the Louvre, it had Picasso and Matisse, it had important collections of African art, and for decades, it offered Black American artists both education and liberation. William H. Johnson arrived in 1926, Palmer Hayden and Hale Woodruff in 1927, Archibald Motley in 1929. Henry Ossawa Tanner, in France since 1891, was a chevalier of the Legion of Honor. The French were not free of race-based assumptions, but their biases were more benign than those institutionalized in the United States—enough so that Motley would later say, “They treated me the same as they treated anybody else.”

One of the great pleasures at the Met is watching these artists feel their way in a heady world. The setting for Motley’s bright and bumptious dance scene Blues (1929) was a café near the Bois de Boulogne frequented by African and Caribbean immigrants, where he would sit and sketch into the night. The subject is unquestionably modern, as are Motley’s smoothed-out surfaces and abruptly cropped edges, but the gorgeous entanglement of musicians and revelers—the chromatic counterpoint of festive clothing and faces that come in dark, medium, and pale—recalls far older precedents, such as Paolo Veronese’s The Wedding Feast at Cana (1562–63), the enormous canvas at the Louvre that people back into when straining for a glimpse of the Mona Lisa.

Woodruff and Hayden took up the theme of the card game, closely associated with Cézanne but also a long-standing trope in European art and African American culture. In Hayden’s Nous Quatre à Paris (“We Four in Paris,” circa 1930) and Woodruff’s The Card Players (1930), the teetering furniture and tilted space set up a pictorial instability that can be seen as a corollary of social pleasure and moral peril, or just the reality of odds always stacked against you. But whereas Woodruff’s jagged styling in The Card Players nods to German expressionism and the African sources behind it, the caricatured profiles in Hayden’s Nous Quatre à Paris call up racist antecedents like Currier and Ives’s once-popular Darktown lithographs. Beautifully drawn in watercolor, it remains a stubbornly uncomfortable image some 95 years after its creation.

William H. Johnson, for his part, spent his years in Europe mostly making brushy landscapes with no obvious social messages. Paired with a woozy village scene by the French expressionist Chaim Soutine, an early Johnson townscape at the Met looks accomplished and unadventurous. But with his wife, the Danish textile artist Holcha Krake, Johnson developed an appreciation for the flat forms and dramatic concision of Scandinavian folk art—a reminder that Africa was not the only place where modernists searched for outsider inspiration—and when he returned to the States, he began working in a jangly figurative mode with no direct antecedent. The dancing couples in his Jitterbugs paintings and screen prints (1940–42) may look simple and cartoonish at first glance, but those pointy knees and high heels are held mid-motion through Johnson’s brilliant machinery of pictorial weights and balances.

There is more than a soupçon of épater le bourgeois in much of this, aimed not just at the buttoned-up white world, but also at the primness of many members of the Black professional class. Langston Hughes, writing in The Nation in 1926, expressed his hope that “Paul Robeson singing Water Boy … and Aaron Douglas drawing strange black fantasies” might prompt “the smug Negro middle class to turn from their white, respectable, ordinary books and papers to catch a glimmer of their own beauty.”

The pursuit of that glimmer accounts for one of the Met exhibition’s most remarkable aspects—its preponderance of great portraiture. There are portraits of the famous, portraits by the famous, portraits of parents and children, and portraits of strangers. Some are large and dazzlingly sophisticated: Beauford Delaney’s 1941 portrait of a naked, teenage James Baldwin in a storm of ecstatic color is a harbinger of the gestural abstractions that Delaney would paint 10 years later. Some are tiny and blunt, like the self-portrait by the self-taught Horace Pippin, celebrated as “the first important Negro painter” by the art collector Albert C. Barnes because of his “unadulterated” ignorance of other art.

This abundance is remarkable because portraiture was not central to European modernism or to 20th-century art in general. Never the most prestigious of genres (too compromised as work-for-hire), the painted portrait had lost its primary raison d’être following the advent of photography in the 1830s and never really recovered. Modernists went on drawing people, but instead of providing a physiognomy to be followed, the sitter was now a toy to be played with. Picasso’s drypoint of the Martinican poet and activist Aimé Césaire is representative, looking very much like a Picasso and not much at all like Césaire. (The Met’s wall text refers to it as a “symbolic portrait.”) The title of the wonderful Edvard Munch painting in the show originally emphasized the polygonal slab of green scarf at its center, not the identity of Abdul Karim, the man wearing it. We might well be curious about Karim—Munch apparently encountered him in a traveling circus’s ethnographic display, and hired him as a driver and model—but Munch wants to lead us away from the distractions of biography and toward color, form, and paint. It was a common ploy. James McNeill Whistler, after all, titled his famous portrait of his mother Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1.

For Black artists and audiences, the situation was different. Painted portraits have always been an extravagance, their mere existence evidence of the value of the people in them. But after 500 years of Western portrait painting, Black faces remained, Alain Locke wrote, “the most untouched of all the available fields of portraiture.” The American Folk Art Museum’s “Unnamed Figures: Black Presence and Absence in the Early American North”—which overlapped with the Met show for a month before closing in March—aimed to fill in that lacuna, with rare commissioned portraits of 19th-century Black sitters, more numerous examples of Black figures (often children) presented as fashionable accessories in portraits of white sitters, and still more dispiriting mass-market material, like a pair of Darktown lithographs showing grossly caricatured Black couples attempting to play tennis.

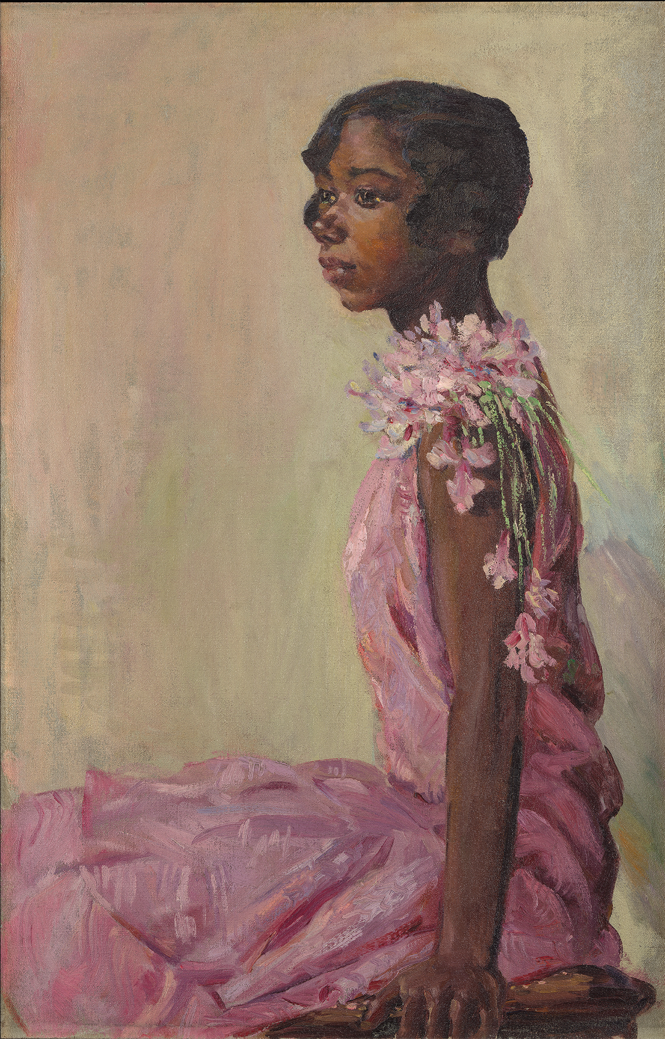

Against this background, portraiture—the quintessential celebration of the individual—could serve a collective purpose. Far from merely gratifying the vanity of a sitter or the creative ego of an artist, it was a correction to the canon, offering proof of how varied beauty, character, or just memorable faces can look. The subject mattered, regardless of the style through which he or she was presented. Laura Wheeler Waring was no avant-gardist—her blend of precision and moderately flashy brushwork gives Girl in Pink Dress (circa 1927) the demeanor of a society portrait. The arrangement is conventional: The sitter is seen in profile, hair in a flapper bob, a spray of silk flowers tumbling over one shoulder like fireworks. But that shade of pink, which might look simpering on a blonde, acquires visual gravitas on this model. She does not smile or acknowledge the viewer. For all her youth and frothy attire, she owns the space of the canvas in no uncertain terms. The dress is frivolous; the picture is not.

Waring, like Munch, does not give us a name to go with the face. For modern artists—whether Black or white, male or female—models, most often young women, were an attribute of the studio, there to be dressed up and arranged like a still life with a pulse. At the Met, they look out at us from frames next to titles that point to their hats and dresses, their jobs and accessories. In some cases, an identity is discoverable—Matisse’s Woman in White (1946) was the Belgian Congolese journalist Elvire Van Hyfte; Winold Reiss’s Two Public School Teachers are thought to have been named Lucile Spence and Melva Price—but many remain anonymous. They are decorative markers for something larger than themselves.

In contrast with Waring’s Girl in Pink Dress, Henry Alston’s Girl in a Red Dress (1934) is stridently modernist, reducing its subject to elemental forms. The erect pose could have been borrowed from a Medici bride, but the elongated neck and narrow head and shoulders were inspired, we are told, by reliquary busts of the Central African Fang people. For Alston, neither European modernism nor Fang tradition was a mother tongue, which helps give the picture its modern edge. He is less interested in the distinctive features of a living individual than in how those features might serve new relationships of form and color.

Other artists, notably the watercolorist Samuel Joseph Brown Jr., succeed in inducing portraiture’s most magical effect—the eerie sense of a real person on the other side of the frame. His Girl in Blue Dress (1936) leans slightly forward, hands casually clasped, a half smile of anticipation on her lips, like someone rapt in conversation. The play of light and the puddled blues and browns are beautifully handled, but the appeal is also social: She looks like someone who would be fun to know.

Black portraiture also carries special clout because of the existential consequences that physical appearance can have in Black life. It was at the core of race-based slavery, and perception of color, which is a painter’s stock in trade, retained its ability to dictate life’s outcomes. Picasso and Matisse might be cavalier about skin tone—painting faces in white and yellow, or green and blue for that matter—but many Black artists recognized it as an optical property riddled with storylines. William H. Johnson gave each of the girls in Three Children (circa 1940) a different-colored hat and a different tone of face. Waring (whose self-portrait resembles my third-grade teacher, a middle-aged woman of Scandinavian extraction) addressed the complexities of color and identity in Mother and Daughter (circa 1927), a double portrait whose subjects exhibit the same aquiline profile but different complexions. Archibald Motley’s The Octoroon Girl (1925) is rosy-cheeked and sloe-eyed, perched on a sofa with the frozen expression of someone expecting bad news. (Motley had a gift for capturing this kind of social discomfort.) The title, which points to the existence of one Black great-grandparent, all but dares the viewer to bring a forensic eye to her face, her hands, the curl of brown hair escaping from under her cloche.

It’s worth noting that for a show about Black culture in the first half of the 20th century, “Harlem Renaissance” gives little space to the continued horror of lynching, the everyday brutality of Jim Crow, and the nationwide rise of the Ku Klux Klan, which reached peak membership around the time that Locke’s Survey Graphic was published. Only a handful of works explicitly address either violence or what Hilton Als, writing about the show in The New Yorker, called the “soul-crushing” realities of the 1920s for Black people. (The most wrenching of these pieces is In Memory of Mary Turner as a Silent Protest Against Mob Violence, a 1919 sculpture by the Rodin protégé Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller.) The emphasis here is on agency and survival, not trauma.

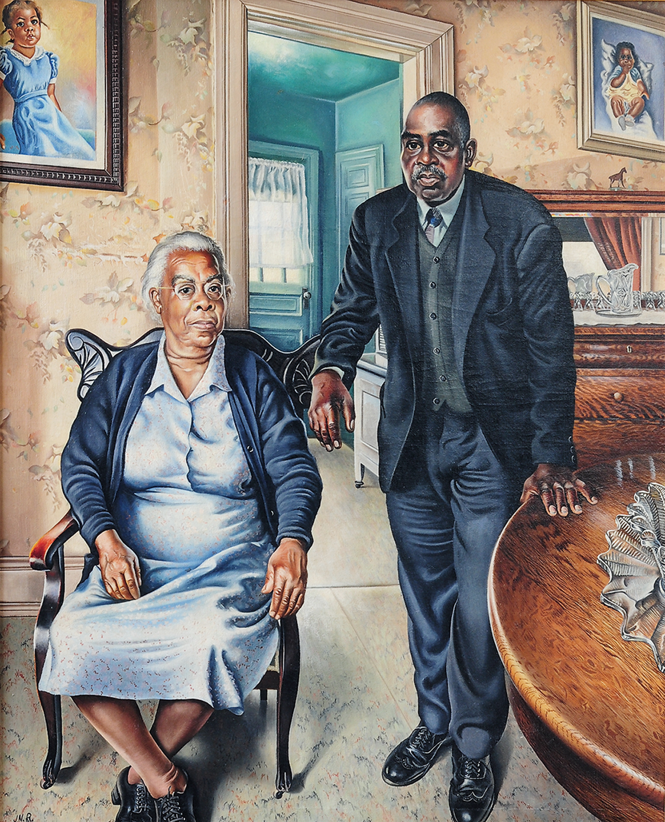

Here, too, the portraits operate as a reservoir of weighty meaning, especially those of elderly relatives. Some sitters, like Motley’s Uncle Bob, were old enough to have been born into slavery. All are endowed by the artists with as much dignity as the conventions of portraiture can muster. Uncle Bob is wearing the plain clothes of a farmer, but is seated like a gentleman, pipe in hand, with a book and a vase of flowers at his elbow. John N. Robinson’s 1942 painting of his grandparents (titled, with curious formality, Mr. and Mrs. Barton) is filled with the hypertrophic detail of a Holbein painting, and as in a Holbein, everything signifies: Mrs. Barton’s look of sober patience; Mr. Barton’s suit, tie, and wing-tip shoes; the oak table and the sideboard with its pressed-glass pitcher and glasses; the framed studio photographs of what must be their great-grandchildren on the wall.

William H. Johnson’s Mom and Dad (1944) departs from tradition in style, but not in purpose. His gray-haired mother faces us from her red rocking chair, hands folded, eyes wide with something like worry. His deceased father presides from his portrait on the wall behind her, his handlebar mustache and celluloid collar decades out of date, but lasting evidence of respectability. These people don’t show a lot of laugh lines, nor the haughtiness endemic to so much society portraiture. Instead there is poise and forbearance, along with the knowledge that they weren’t bought cheap.

Harlem was pronounced the “Mecca of the New Negro” 99 years ago. That cultural renaissance is as far from us today as the contributors to that Survey Graphic issue were from the presidency of John Quincy Adams. The Met’s is not the first big show to survey Black artists’ achievements in that era, but it is the most ambitiously global, a quality that makes that vanished world feel more familiar than we might expect—a place where Black artists move back and forth across the Atlantic, absorbing every influence on offer, coping with questions of identity, and struggling to make ends meet. Against this, the abundance of photographs—the marching men in bowler hats, the marcelled ladies who lunch, the couple posing in raccoon coats with their shiny roadster like Tom and Daisy Buchanan—works to remind us of the temporal distance that painting and sculpture can collapse.

Attempting to define modernism is a thankless task. But a few years ago, the painter Kerry James Marshall offered this observation: “Modern is not so much an appearance or a subject matter. It is, indeed, a process of always becoming and a negotiation for attention between the contemporary artist’s ego and the legacy of previous masterworks.” At its best, what “Harlem Renaissance” provides is a chance to witness that becoming, to peek at those negotiations in progress, through the work of artists whose achievements have, in many cases, been insufficiently celebrated. Which brings us back to that Aaron Douglas still life.

History painting went out of vogue in the 20th century because modern art stopped believing in simple stories. Douglas’s narrative paintings, beautifully designed and eye-catching though they can be, are throwbacks—spectacular, efficient, impersonal engines for delivering public-service messages. The still life is different. Sure, the sloping magnolia branches and off-kilter Titian conform to his love of diagonals on diagonals. But the things represented are not abstractions; they are objects that lived in the real world—the leaves are curled and brown in spots; the margins of the Titian are torn and stained. What is pictured isn’t a lesson, but a meditation on learning, and on the many ways that meaning can make itself felt.

Douglas was a native Kansan. It is possible that Titian’s Nicodemus echoed, for him, the abolitionist song “Wake Nicodemus,” whose hero, a slave “of African birth,” was the namesake of a Kansas town founded after the Civil War by the formerly enslaved. Or maybe Douglas just loved that painting in the Louvre. Or both.

This article appears in the July/August 2024 print edition with the headline “The Harlem Renaissance Was Bigger Than Harlem.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What's Your Reaction?