The Bump-Stocks Case Is About Something Far Bigger Than Gun Regulations

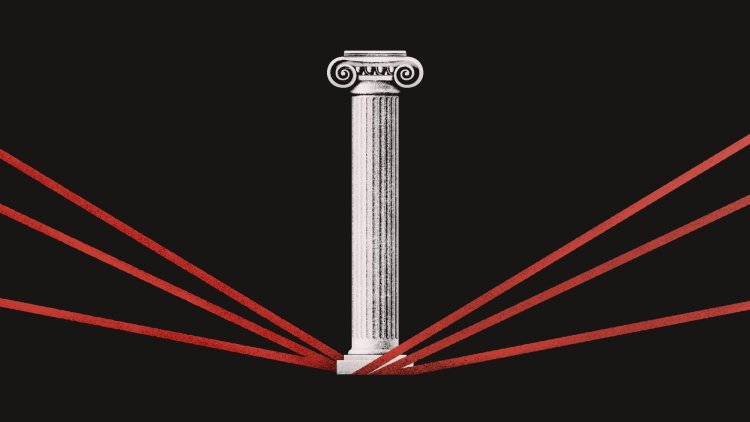

It’s about the fundamentals of how American government works.

Sometimes a Supreme Court case appears to be about a minor technical issue, but is in fact a reflection of a much broader and significant legal development—one that could upend years of settled precedent and, with it, basic understandings of the allocation of powers across our system of government.

That’s exactly what is happening in Garland v. Cargill, a case for which the Supreme Court heard oral argument at the end of February. The specific challenge in the case is to a Trump-era federal regulation banning all “bump stocks”—contraptions that, when attached to semiautomatic firearms, allow them to discharge ammunition even more rapidly and without additional pulls of the trigger. Although the specific legal issue before the justices reduces to the technical question of whether a bump stock thus converts a semiautomatic rifle into a “machine gun,” Garland v. Cargill is a much broader illustration of—and referendum on—the real-world implications of the Court’s mounting hostility toward federal administrative agencies. That’s because the real question in Cargill is not whether a rifle with a bump stock counts as a machine gun; the real question is whether we’re ready for a world in which that question will be resolved not by an expert executive-branch agency that answers directly to the president, but by federal judges who answer to no one.

The basic dispute in Cargill is easy enough to describe: On October 1, 2017, a single shooter at a Las Vegas music festival killed 60 people and wounded almost 500 more—the deadliest shooting by a lone gunman in U.S. history. Part of what made it possible for the shooter to discharge so many rounds of ammunition (more than 1,000) in such a short amount of time was his use of bump stocks. At that time, the specific bump stocks the shooter used were not regulated by federal authorities.

In response, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF)—a Justice Department agency that is tasked with interpreting and administering federal gun-control laws—adopted a new regulation instructing that, given how they transformed the mechanical function of semiautomatic rifles, all bump stocks transformed semiautomatic rifles into machine guns, and were thus effectively banned by federal law. The rule gave those who already owned the devices 90 days to turn them in or destroy them before civil or criminal penalties would apply.

[Read: The plan to incapacitate the federal government]

The rule was promptly challenged in multiple federal courts. And although some of the lawsuits argued that the rule violated the Second Amendment, the central objection was that it exceeded the ATF’s statutory authority—because bump stocks are not, in fact, machine guns, and the ATF was authorized by Congress to prohibit only things that were. It was that argument that won the day in the hyper-conservative New Orleans–based U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which, breaking from the other federal courts of appeals to consider the matter, ruled in 2022 that the ATF lacked the authority to regulate bump stocks, because the relevant statutes didn’t clearly support its interpretation of “machine gun.”

Not so long ago, a case like Cargill would not have come down to whether a court agreed with an agency’s interpretation of a statute Congress had tasked it with enforcing. Indeed, decades of administrative law, including but not limited to the Supreme Court’s 1984 ruling in Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, recognized that agency experts were often in a better position to resolve ambiguities in the statutes that Congress tasked them with enforcing than federal judges were. Thus, it had long been settled that, so long as an agency’s interpretation of ambiguous language in a statute (like what counts as a machine gun) was reasonable, the agency was allowed to act based upon that interpretation.

But as the Supreme Court has taken a sharp right turn in recent years, one of the areas in which it has moved most aggressively is to rein in such deference. The first salvo was the rise of the “major-questions doctrine,” which denies agencies the power to regulate at all on matters of “vast economic or political significance” unless Congress has clearly and specifically authorized the precise regulation at issue. In the 2023 student-loan case, for instance, it wasn’t enough for the Supreme Court that Congress had given the Secretary of Education broad authority to “waive or modify any statutory or regulatory provision [applicable to student-loan programs] as the Secretary deems necessary in connection with a war or other military operation or national emergency.” Because that sweeping delegation hadn’t specifically authorized loan forgiveness, the program was unlawful. Indeed, whether a particular matter is of “vast economic or political significance” will often be in the eye of the beholder—the judge, not the agency or the Congress that passed the underlying statute in the first place.

That was already worrying enough, but what’s alarming in Cargill is that the Court is in the midst of getting rid of deference to agencies outside of the “major questions” context, too. Thus, instead of debating whether ATF’s reaction to the Las Vegas shooting was reasonable (which it clearly was), the oral argument before the Supreme Court devolved into the justices struggling to understand the exact mechanical function of a bump stock—so that they could decide for themselves whether or not it fits within the statutory definition of a “machine gun.” As even a cursory perusal of the transcript reveals, this wasn’t a high-minded debate about broader points of law; it was nine neophytes trying to understand the mechanics of something they’ve never touched solely by having it described to them. One comes away from the transcript with the sense that the argument would have been far more productive had it been held on a shooting range. So instead of debating whether the executive branch overreacted or not, the debate was about what, in the abstract, the justices would have done in its place.

But as troubling as it is to have the justices substituting their judgment for those of executive-branch agencies that are staffed with experts in the field, the real issue going forward is going to be the lack of expertise of lower-court judges. After all, the Supreme Court hears roughly 60 cases each term, a small subset of which are these kinds of regulatory disputes. The overwhelming majority of the thousands of challenges to federal rules filed each year are conclusively resolved by lower federal courts—where litigants from across the political spectrum have become much more sophisticated in steering their cases to ideologically or politically sympathetic judges in both the district courts and the courts of appeals.

[Read: The Supreme Court once again reveals the fraud of originalism ]

Consider, in this respect, what’s happening in Texas. A single judge in Amarillo, Matthew Kacsmaryk, hears 100 percent of new civil cases filed in Texas’s northernmost city, from which appeals go to the Fifth Circuit. It’s no coincidence that litigants challenging policies on a nationwide basis—like the Alliance Defending Freedom’s challenge to mifepristone—are steering their cases to the Texas panhandle. And although this kind of judge-shopping is a bit harder for left-leaning plaintiffs to pursue (because of quirks in how different states divide their districts), we already saw, during the Trump administration, a concentration of challenges to federal policies in California, Maryland, New York, and other Democratic strongholds. The demise of deference to agencies is thus a threat to all executive-branch policies, regardless of whose ox is currently being gored.

There will, of course, be cases in which the courts ultimately side with the agencies. But whether or not Cargill ends up as one of them, the February 28 oral argument was a sobering lesson in the very real consequences of transferring this kind of power away from expert executive-branch agencies and to unelected, generalist judges—of conditioning the executive branch’s ability to react to the regulatory lessons of tragedies such as the Las Vegas shooting on the agreement of those federal judges least likely to be sympathetic to the problem that the executive branch is trying to solve. And although Congress could clarify these ambiguities or otherwise fill in some of these statutory gaps, even a well-functioning Congress will never be able to fill all of them, and not just for guns but for industries across the board—pharmaceuticals, cars, natural-resource extraction, home goods, you name it. The result is not, as critics of administrative deference regularly claim, better for “democracy.” Instead, if it’s better for any one thing, it’s deregulation. And maybe that’s the point.

What's Your Reaction?