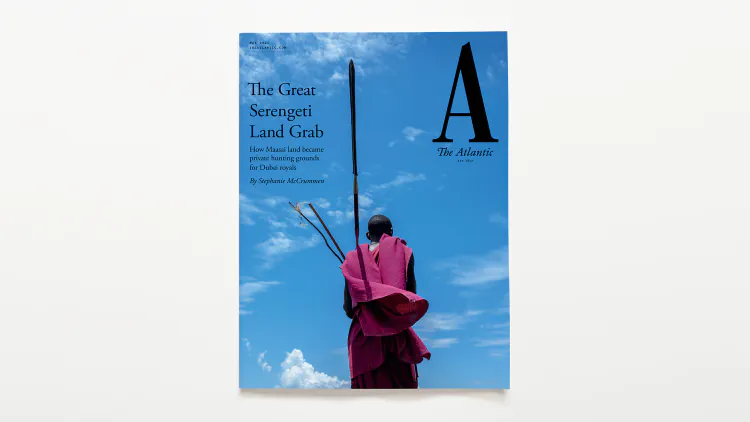

<em>The Atlantic</em>’s May Cover Story: Stephanie McCrummen on the “Great Serengeti Land Grab”

For The Atlantic’s May cover story, “The Great Serengeti Land Grab,” staff writer Stephanie McCrummen reports from Tanzania on how Gulf princes, wealthy tourists, and conservation groups are displacing the Maasai people. McCrummen, who was once an East Africa bureau chief, reports extensively from the region, speaking with Tanzanian government officials and telling the story of the Maasai as they confront their ongoing displacement. The Maasai migrated to northern Tanzania 400 years ago, becoming stewards of a land that encompasses hundreds of thousands of square miles of grassy plains, woodlands, rivers, and lakes, as well as some of the most spectacular wildlife on the planet. British colonial authorities, in the wake of their own arrival, went on to establish part of the land area as the Serengeti National Park, followed by UNESCO declaring the area a World Heritage Site. Western tourists arrived to experience a version of Africa they’d been promised in movies, and Tanzanian author

For The Atlantic’s May cover story, “The Great Serengeti Land Grab,” staff writer Stephanie McCrummen reports from Tanzania on how Gulf princes, wealthy tourists, and conservation groups are displacing the Maasai people. McCrummen, who was once an East Africa bureau chief, reports extensively from the region, speaking with Tanzanian government officials and telling the story of the Maasai as they confront their ongoing displacement.

The Maasai migrated to northern Tanzania 400 years ago, becoming stewards of a land that encompasses hundreds of thousands of square miles of grassy plains, woodlands, rivers, and lakes, as well as some of the most spectacular wildlife on the planet. British colonial authorities, in the wake of their own arrival, went on to establish part of the land area as the Serengeti National Park, followed by UNESCO declaring the area a World Heritage Site. Western tourists arrived to experience a version of Africa they’d been promised in movies, and Tanzanian authorities started leasing blocks of lands to foreign hunting and safari companies, as well as to the Dubai royal family. But, as McCrummen writes, “the threat unfolding now is of greater magnitude.”

Tanzania’s president, Samia Suluhu Hassan, took office in 2021. In one of her first major speeches, she emphasized the renewed role of tourism in the country and how “we agreed that people and wildlife could cohabitate, but now people are overtaking the wildlife.” Not long after the speech, officials announced plans to resettle the roughly 100,000 Maasai living in and around the area to “modern houses” in another part of the country. McCrummen reports on how compounds were bulldozed and houses were crushed; families were forcibly removed, shot at, and beaten; cattle were seized by the tens of thousands; and the finest land in northern Tanzania was set aside for conservation, which turned out to mean “bespoke expeditions” for trophy hunters and tourists—anything and anyone except the Maasai.

McCrummen interviews Albert Msando, a district commissioner who was empowered to speak on behalf of President Hassan. Msando told McCrummen that he could understand the Maasai’s concern about losing their culture, even if he had little sympathy for it. “Culture is a fluid thing,” Msando said, adding: “The Maasai are not exempted from acculturation or cultural acclimatization or cultural extinction.”

McCrummen focuses on the plight of a Maasai man named Songoyo, who was displaced from his home and is struggling to rebuild his life. She follows Songoyo as he attempts to raise enough money to buy a single cow, because, as McCrummen writes, “that was the starting point of what it meant to be a Maasai man, which was what he still wanted to be.” The Maasai have tried to resist their displacement through appeals to the United Nations, the European Union, the East African Court of Justice, and Vice President Kamala Harris, when she visited Tanzania, in 2023. They have produced original reports and unearthed old maps and village titles to prove that the land is theirs by law—but, as McCrummen reports, it has ultimately been to no avail.

“The Great Serengeti Land Grab” was published today in The Atlantic. Please reach out with any questions or requests.

Press Contact:

Sammi Sontag | The Atlantic

[email protected]

What's Your Reaction?