The Alabama Embryo Opinion Is Part of a Larger Plan

An insurgent religious movement is beginning to feel its strength.

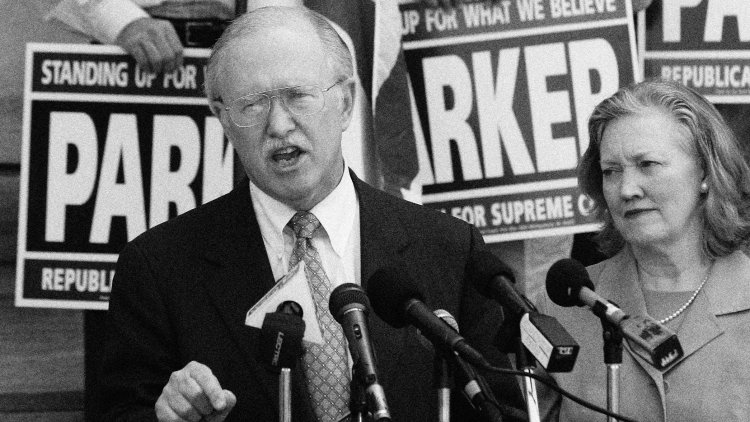

Not long before Alabama Supreme Court Chief Justice Tom Parker issued an opinion citing the Bible as the basis for declaring that frozen embryos are people, he was a guest on a YouTube show hosted by a self-described prophet named Johnny Enlow. Parker’s appearance on such a program reveals a lot about the rising political power of the country’s fastest-growing Christian movement.

Over the years, Enlow has written about how “a government can potentially function as a virtual theocracy” if leaders faithfully listen to God. He is a top promoter of the idea that Christians need to assert dominion over “seven mountains” of life—government, business, family, education, media, religion, and the arts. In recent months, he has said that Donald Trump could be justified in calling for “revolution” and interviewed a former Army major who runs an Idaho tactical-weapons training camp billed as being for “Christian men who believe the times warrant a high standard of firearms readiness.”

[Stephanie McCrummen: The woman who bought a mountain for God]

Now Enlow was introducing Parker as another “asset,” a “fellow Kingdom lover.” He invited the 72-year-old judge to talk about how God had called him “to the mountain of government.”

“As you have emphasized in the past, we have abandoned those seven mountains, and they’ve been occupied by the opposite side,” said Parker, who was elected to Alabama’s highest court in 2004 and has been chief justice since 2019. “I will say that God created government, and the fact that we have let it go into the possession of others is heartbreaking.” The two went on talking about the Holy Spirit and, quoting the Book of Isaiah, about “restoring the judges as in the days of old.”

This language, which can be mystifying to those not steeped in it, is commonly categorized as fundamentalism or Christian nationalism. But those terms do not adequately capture the scope and ambitions of the rapidly growing charismatic Christian movement with which Parker has publicly associated himself—a world of megachurches, modern-day apostles and prophets, media empires, worship bands, and millions of followers that is becoming the most aggressive faction of the Christian right and the leading edge of charismatic Christianity worldwide.

These are not blue-blazer Southern Baptists. This is the demon-mapping, prophecy-believing, spiritual-warfare, end-times-army, take-the-U.S.-Capitol-for-the-heavenly-Kingdom crowd—a movement that has its own history, its own superstars, and an agenda that goes beyond saving souls, or drawing upon faith to influence policy, as Americans of many religions do.

The movement is often called the New Apostolic Reformation, a phrase coined in the mid-1990s by a theology professor named C. Peter Wagner and once openly embraced by many leaders. Wagner was trying to describe what he said he was witnessing in churches not only in the United States but also in parts of Latin America, Africa, and China: explosive growth, miracles, signs and wonders. He believed that a fresh wave of the Holy Spirit was moving around the globe, obliterating denominational differences, banishing demonic strongholds, raising up new apostles and prophets with new dreams and visions for humanity. A great restoration of the first-century Church was under way, he contended. The end game would be an actual, earthly Kingdom of God.

[Peter Wehner: Where did evangelicals go wrong?]

Wagner himself became a major figure in the movement, taking part in the first international convening of apostles in 2000 and writing books such as Dominion! How Kingdom Action Can Change the World. Years later, the movement is supplying an argument for authoritarianism, becoming a political force behind the rise of leaders such as Trump and Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro. Prophets and apostles are everywhere, describing God-given dreams and visions on their podcasts and social media. The movement is competing with Catholicism in many Brazilian villages; setting up in storefronts in Nairobi, Kenya; and filling moribund churches from California to the Deep South.

I have visited many of these churches across the United States in my reporting. Inside, the walls are usually blank. No portraits of Jesus, no crosses. Some have Broadway-quality lighting. Instead of a pulpit, there is typically a huge screen showing futuristic scenes—spinning stars, crashing waves. Praise bands blast songs with simple chord progressions and mantralike choruses about submission to God. Many people pray lying prostrate on the floor. Sermons explain life as an ever-escalating spiritual battle between the forces of God and Satan, one in which Mr. Splitfoot might take the form of Joe Biden, Democrats, your local librarian, homosexual impulses, drugs, abortion—anything and anyone in the way of God’s Kingdom.

Crucially, followers are urged to join in this great, rolling drama. In sermons, YouTube shows, books, and training academies, leaders in the movement urge people to listen to God and figure out which of the seven mountains is theirs.

A North Carolina apostle named Greg Hood started something called Kingdom University to create what he calls Kingdom citizens. Businesspeople have started “Kingdom-aligned” investment firms. A woman I profiled last year had felt God telling her to buy a mountain in Western Pennsylvania, and she did, aiming to build a retreat center for people to learn their Kingdom assignments.

In Alabama, Justice Tom Parker decided that his mountain is government.

“When the judges are restored, revival can flow,” he said on a prayer call convened last March by a prominent apostle named Clay Nash, one of 50 such calls in 2023 that routinely featured state legislators, members of Congress, judges, and other officials reporting on their progress building the Kingdom. “So, I have been laboring. I’m part of it in Alabama … At least as chief justice, I can help prepare the soil of the hearts, exposing the judges around the state to the things of God. I want to ask that we focus, going forward, on judges as one of the components to revival in this nation.”

On the steps of the Alabama capitol building last year, Parker—who declined to be interviewed for this article—introduced Sean Feucht, a popular singer in the movement who was touring state capitals and who told one crowd, “We want believers to be the ones writing the laws! Yes!” and “We want God to be in control of everything!” Parker prayed for “a comprehensive awakening across the state that will be so powerful that it will bring forth reformation in government that will affect the nation.”

On Enlow’s show, the host asked Parker to talk about how he felt doing his job.

“Do you feel angels are attentive?” Enlow asked him. “Do you feel warfare?”

“We know God equips those he calls,” Parker said. “And I am very aware he is equipping me with something for the specific situation I am facing.”

“So you do feel like the Holy Spirit is there?” Enlow asked him.

“Yes,” Parker said.

The judge went on to explain his legal philosophy. He said that there is natural law and God’s law, and that God’s law is necessary because man cannot trust his own reason. “Because of the impact of the fall of man in the Garden, man’s reason became corrupted and could no longer properly discern God’s law from nature,” Parker said. “So he had to give them the revealed law. The holy scripture.”

[Read: How politics poisoned the evangelical church]

Not long after recording the show, the judge issued his concurring opinion in the in-vitro-fertilization case, eschewing secular sources to cite the Books of Genesis, Exodus, and Jeremiah as the ultimate authority in defining “the sanctity of human life.” The backlash has been swift, and the Alabama legislature voted Thursday to protect doctors doing IVF from criminal or civil liability if embryos are destroyed. But the New Apostolic Reformation remains a gathering force in American politics.

“The Parker point of view, the NAR point of view, is deep and complicated,” Frederick Clarkson, a research analyst who has been studying the Christian right for decades, told me. He considers the NAR to be one of the most important shifts in Christianity in modern times. “Christian nationalism is a handy term, but it is a box into which NAR does not quite fit,” Clarkson said—the movement is “so much bigger than that.”

The people who advanced the notion that God was using Trump were not merely Christian nationalists. They were prominent apostles such as Dutch Sheets, who is as familiar to those in the movement as Billy Graham once was to your average Southern Baptist.

Sheets was a key figure in the run-up to January 6, exhorting his followers to go to Washington, D.C., to take the Capitol not just for Trump but for God. They came by the busload, bearing the Revolutionary War–era flag that Sheets popularized and repurposed as a symbol of the Kingdom movement.

The flag is white with a green pine tree and the words An Appeal to Heaven, and it is now posted outside the district office of House Speaker Mike Johnson. As wild and hyperbolic as the movement can seem to outsiders, believers continue to prove their seriousness, in Alabama and beyond.

What's Your Reaction?