Starbucks’ Most Beloved Offering Is Disappearing

It’s the end of free bathrooms—and of a particular fantasy.

In Blaine, Washington, there is a very special Starbucks. Like every Starbucks, this one has tables and chairs and coffee and pastries and a pacifying sort of vibe. Also like (most) Starbucks, it has a bathroom, open to anyone who walks in. The bathroom is important because this Starbucks is located about three-quarters of a mile past Peace Arch, the busiest border crossing west of Detroit, and a wretched, wretched place where you can sometimes get stuck in a car for several hours without warning. The Blaine Starbucks looks out onto the magnificent Semiahmoo Bay and is, I guess for that reason, designed like a working lighthouse; at night, you can see it from all over the city center. The metaphor is almost too beautiful: Here is Starbucks and here is its warm light, guiding you to shore. Just about as soon as your huddled masses enter America, Starbucks is ready to take care of you. Do you need to pee? Of course you do.

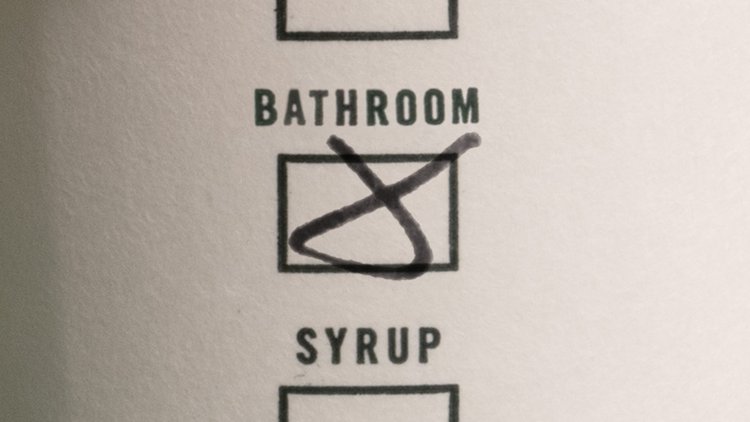

Too bad. Last week, Starbucks, which has had a new CEO since September, announced an updated “Code of Conduct,” which mandates that the coffee shop’s spaces—including “cafes, patios and restrooms”—will soon be for paying customers only. “There is a need,” Sara Trilling, the president of Starbucks North America, wrote in a letter to store managers, “to reset expectations for how our spaces should be used, and who uses them.” Starbucks—the chain that took over the world by being everywhere and for everyone—is now a little less for everyone.

[Read: The luxury makeover of the worst pastry on Earth]

The change appears to be pitched at returning Starbucks to its former glory, when Starbucks was, in theory at least, not just a store but also a gathering space. “If you look at the landscape of retail and restaurants in America, there is such a fracturing of places where people meet,” the company’s famed former CEO, Howard Schultz, told an industry publication in 1995. “There’s nowhere for people to go. So we created a place where people can feel comfortable.” Starbucks was to feel like a “third place,” an idea borrowed from the sociologist Ray Oldenburg: not home, not work, but somewhere else—a place where community is formed and civility is fostered; a place, like church, where people gather on equal footing and find meaning.

For a while, it actually worked, in both the high-minded sense and the business sense. Starbucks was America’s, and then the world’s, second living room, a place where people were happy to spend their money every day. The chairs were comfortable enough, and all those laptop-clackers and book-readers were like extras in the movie everyone thinks they are starring in. People may not have been forging deep connections with their fellow man at Starbucks, but they were, demonstrably, living their lives there: Americans have given birth at Starbucks, proposed at Starbucks, gotten married at Starbucks, died at Starbucks. In 1987, there were 17 Starbucks stores. In 2007, there were more than 15,000, in 43 countries.

But now, the internet has become our third space, and Starbucks has become, by and large, a well-outfitted to-go counter. Seven out of 10 Starbucks orders are completed via mobile app or drive-through. Walk into any store and you will see harried baristas frantically making drinks for people whose goal is certainly not to build community but rather to sprint in and sort through the forest of Frappuccinos to find theirs, if it’s ready. Last year, on a podcast, Schultz, who is no longer Starbucks’ CEO but is still a major shareholder, described the scene as “a mosh pit” (and not in a positive way). During the second quarter of 2024, transactions dropped 7 percent, the chain’s worst quarter that didn’t involve a pandemic or a great recession. Three months later, Brian Niccol took over as CEO. His second day on the job, he released a statement titled “Back to Starbucks.” It described the café as “a gathering space, a community center where conversations are sparked, friendships form, and everyone is greeted by a welcoming barista.”

Many customers “still experience this magic every day, but in some places—especially in the U.S.—we aren’t always delivering,” Niccol wrote. “It can feel transactional, menus can feel overwhelming, product is inconsistent, the wait too long or the handoff too hectic. These moments are opportunities for us to do better.”

Though the new code of conduct does not include the word loitering, the implication that Starbucks wants to ban it is there: The company wants to be a place for people to hang out—but not just any people. This is, of course, any company’s prerogative. Still, Starbucks making this decision in the name of becoming a better “community center” is both patently silly and a little delusional. Community centers don’t typically require you to buy a cake pop to enter. And to the degree that Starbucks brings people together, it is because they are all using the same services (Wi-Fi, outlets, air-conditioning, water, bathrooms) at the same time. It’s not a church; it’s a rest stop.

[Read: Eat your vegetables like an adult]

But the corporate grandiosity also speaks to something somewhat profound, and sad, about what Starbucks does offer, and what no other large-scale entity does. Public restrooms, once an ordinary feature of urban American life, are disappearing. So are public water fountains. One in 15 Americans does not have access to high-speed internet, and widespread, free, municipal Wi-Fi, a dream of the techno-utopian 2000s, has yet to come to pass. Libraries across the country are cutting their hours. All the people who were left without a place to work after the pandemic closed their offices do not necessarily have a public replacement. Urban spaces are being explicitly designed to be annoying or impossible to sit in. Starbucks is, or was, a respite from all that, but of course, making a global corporation a municipal utility is not exactly a long-term solution.

Starbucks is a business. The company formalized its open-door bathroom policy several years ago, after two Black men were arrested for trying to use the facilities while having a meeting, the video of which went viral and caused a public-relations crisis. Now Starbucks is reversing it, also, presumably, for reasons having to do with being a business, one that is accountable to its shareholders every quarter. (The company’s stock price has indeed risen by about 6 percent since the bathroom change was announced.) Starbucks doesn’t sell community, because community isn’t something you can buy—it sells coffee because coffee is something you can.

What's Your Reaction?