Six Months Inside One of America’s Most Dangerous Industries

What I learned on the line at a Dodge City slaughterhouse.

This article was published online on June 14, 2021.

This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here.

On the morning of May 25, 2019, a food-safety inspector at a Cargill meatpacking plant in Dodge City, Kansas, came across a disturbing sight. In an area of the plant called the stack, a Hereford steer had, after being shot in the forehead with a bolt gun, regained consciousness. Or maybe he had never lost it. Either way, this wasn’t supposed to happen. The steer was hanging upside down by a steel chain shackled to one of his rear legs. He was showing what is known in the euphemistic language of the American beef industry as “signs of sensibility.” His breathing was “rhythmic.” His eyes were open and moving. And he was trying to right himself, which the animals commonly do by arching their back. The only sign he wasn’t exhibiting was “vocalization.”

The inspector, who worked for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, told employees in the stack to stop the moving overhead chain to which the cattle were attached and “reknock” the steer. But when one of them pulled the trigger on a handheld bolt gun, it misfired. Someone brought over another gun to finish the job. “The animal was then stunned adequately,” the inspector wrote in a memorandum describing the incident, noting that “the timeframe from observing the apparent egregious action to the final euthanizing stun was approximately 2 to 3 minutes.”

Three days after the incident occurred, the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service, citing the plant’s history of compliance, put the plant on notice for its “failure to prevent inhumane handling and slaughter of livestock.” FSIS ordered the plant to create an action plan to ensure that such an incident didn’t happen again. On June 4, the agency approved a plan submitted by the plant’s manager and said in a letter to him that it would defer a decision about punishment. The chain could keep moving, and with it the slaughtering of up to 5,800 cows a day.

[Eric Schlosser]: America’s slaughterhouses aren’t just killing animals

The first time I stepped foot in the stack was late last October, after I had been working at the plant for more than four months. To find it, I arrived early one day and worked my way backwards down the chain. It was surreal to see the slaughter process in reverse, to witness step-by-step what it would take to reassemble a cow: shove its organs back into its body cavities; reattach its head to its neck; pull its hide back over its flesh; draw blood back into its veins.

During my visits to the kill floor, I saw a severed hoof lying inside a metal sink in the skinning room, and puddles of bright-red blood dotting the red-brick floor. One time, a woman in a yellow synthetic-rubber apron was trimming away flesh from skinless, decapitated heads. A USDA inspector working next to her was doing something similar. I asked him what he was cutting. “Lymph nodes,” he said. I found out later that he was performing a routine check for diseases and contamination.

On my last trip to the stack, I tried to be inconspicuous. I stood against the back wall and watched as two men standing on a raised platform cut vertical incisions down the throat of each passing cow. As far as I could tell, all of the animals were unconscious, though a few of them involuntarily kicked their legs. I watched until a supervisor came over and asked what I was doing. I told him I wanted to see what this part of the plant was like. “You need to leave,” he said. “You can’t be here without a face shield.” I apologized and told him that I would get going. I couldn’t have stayed for much longer anyway; my shift was about to start.

Getting a job at the Cargill plant was surprisingly easy. The online application for “general production” was six pages long. It took less than 15 minutes to fill out. At no point was I required to submit a résumé, let alone references. The most substantial part of the application was a 14-question form that asked things like:

“Do you have experience working with knives to cut meat (this does not include working in a grocery store or deli)?”

No.

“How many years have you worked in a beef production plant (example: slaughter or fabrication, not a grocery store or deli)?”

No experience.

“How many years have you worked in a production or plant environment (example: assembly line or manufacturing work)?”

Zero.

Four hours and 20 minutes after hitting “Submit,” I received an email confirmation for a phone interview the next day, May 19, 2020. The interview lasted three minutes. When the woman conducting it asked me for the name of my last employer, I told her that it was the First Church of Christ, Scientist, the publisher of The Christian Science Monitor. I had worked at the Monitor from 2014 to 2018. For the last two of those four years, I was its Beijing correspondent. I had quit to study Chinese and freelance.

“And what did you do there?” the woman asked about my time at the Church.

“Communications,” I said.

The woman asked a couple of follow-up questions about when I quit and why. During the interview, the only question that gave me pause was the final one.

“Do you have any issues or concerns working in our environment?” she asked.

After hesitating for a moment, I replied, “No, I don’t.”

With that, the woman said that I was “eligible for a verbal, conditional job offer.” She told me about the six positions for which the plant was hiring. All were for the second shift, which at the time was running from 3:45 in the afternoon to between 12:30 and 1 o’clock in the morning. Three of the jobs were in harvesting, the side of the plant more commonly known as the kill floor, and three were in fabrication, where the meat is prepared for distribution to stores and restaurants.

I quickly decided that I wanted a job in fab. Temperatures on the kill floor can approach 100 degrees in the summer, and, as the woman on the phone explained, “the smell is stronger because of the humidity.” Then there were the jobs themselves, jobs like removing hides and “dropping tongues.” After you remove the tongue, the woman said, “you do have to hang it on a hook.” Her description of fab, on the other hand, made it sound less medieval and more like an industrial-scale butcher shop. A small army of assembly-line workers saw, cut, trim, and package all of the meat from the cows. The temperature on the fab floor ranges from 32 to 36 degrees. But, the woman told me, you work so hard that “you don’t feel the cold once you’re in there.”

We went over the job openings. Chuck cap puller was immediately out because it involved walking and cutting at the same time. The next to go was brisket bone for the simple reason that having to remove something called brisket fingers from in between joints sounded unappealing. That left chuck final trim. That job, as the woman described it, consisted entirely of trimming pieces of chuck “to whatever spec it is that they’re running.” How hard could that be? I thought to myself. I told the woman that I would take it. “Perfect,” she said, and went on to tell me my starting pay ($16.20 an hour) and the conditions of my job offer.

A couple of weeks later, after a background check, a drug screening, and a physical exam, I got a call about my start date: June 8, the following Monday. The drive to Dodge City from Topeka, where I had been living with my mom since mid-March because of the coronavirus pandemic, takes about four hours. I decided that I would leave on Sunday.

On the evening before I left, my mom and I went to my sister and brother-in-law’s house for a steak dinner. “It might be the last one you ever have,” my sister said when she called to invite us over. My brother-in-law grilled two 22-ounce rib eyes for him and me and a 24-ounce sirloin for my mom and sister to split. I helped my sister cook the side dishes: mashed potatoes and green beans sautéed in butter and bacon grease. The quintessential home-cooked meal for a middle-class family in Kansas.

The steak was as good as any I’ve had. It’s hard to describe it without sounding like an Applebee’s commercial: charred crust, juicy and tender meat. I tried to eat slowly so that I could savor every bite. But soon I was caught up in conversation, and I finished eating without thinking about it. In a state where cows outnumber people two to one, where more than 5 billion pounds of beef are produced annually, and where many families—including mine, when my three sisters and I were younger—fill their deep freezer once a year with a side of beef, it’s easy to take a steak dinner for granted.

The Cargill plant is on the southeastern outskirts of Dodge City, just down the road from a slightly larger meatpacking plant owned by National Beef. The two facilities sit at opposite ends of what is surely the most noxious two-mile stretch of road in southwestern Kansas. Situated close by is a wastewater-treatment plant and a feedlot. On many days last summer, I found the stench of lactic acid, hydrogen sulfide, manure, and death to be nauseating. The oppressive heat only made it worse.

The High Plains of southwestern Kansas are home to four major meatpacking plants: the two in Dodge City, plus one in Liberal (National Beef) and another near Garden City (Tyson Foods). That Dodge City became home to two meatpacking plants is a fitting coda to the town’s early history. Founded in 1872 along the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad, Dodge City was originally an outpost for buffalo hunters. After the herds that once roamed the Great Plains were decimated—to say nothing of what happened to the Native Americans who’d once lived there—the city turned to the cattle trade.

Practically overnight, Dodge City became, in the words of a prominent local businessman, “the greatest cattle market in the world.” This was the era of lawmen like Wyatt Earp and gunfighters like Doc Holliday, of gambling and shoot-outs and barroom brawls. To say that Dodge City is proud of its Wild West heritage would be an understatement, and nowhere is that heritage more celebrated—some might say mythologized—than at the Boot Hill Museum. Located at 500 West Wyatt Earp Boulevard, near Gunsmoke Street and the Gunfighters Wax Museum, the Boot Hill Museum is anchored by a full-scale replica of the once-famous Front Street. Visitors can enjoy a sarsaparilla at the Long Branch Saloon or shop for handmade soap and homemade fudge at the Rath & Co. General Store. Entry to the museum is free for Ford County residents, a deal that I took advantage of many times last summer after I moved into a one-bedroom apartment near the local VFW.

Yet for all its dime-novel-worthy stories, Dodge City’s Wild West era was short-lived. In 1885, under growing pressure from local ranchers, the Kansas legislature banned Texas cattle from the state, bringing an abrupt end to the cattle drives that had fueled the town’s boom years. For the next seven decades, Dodge City remained a quiet farming community. Then, in 1961, a company called Hyplains Dressed Beef opened the first meatpacking plant in town (the same one now operated by National Beef). In 1980, a subsidiary of Cargill opened its plant down the road. The beef industry had returned to Dodge City.

With a combined workforce of more than 12,800 people, the four meatpacking plants are among the largest employers in southwestern Kansas, and all of them rely on immigrants to help staff their production lines. “The packers followed the maxim of ‘Build it and they will come,’ ” Donald Stull, an anthropologist who has studied the meatpacking industry for more than 30 years, told me. “And that’s basically what happened.”

According to Stull, the boom started in the early 1980s with the arrival of refugees from Vietnam and migrants from Mexico and Central America. In more recent years, refugees from Myanmar, Sudan, Somalia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo have all come to work in the plants. Today, nearly one in three Dodge City residents is foreign-born, and three in five are Latino or Hispanic. When I arrived at the plant on my first day of work, I was greeted by four banners at the entrance, one each in English, Spanish, French, and Somali, warning employees to stay home if they were exhibiting symptoms of COVID-19.

I spent much of my first two days at the plant with six other new hires in a windowless classroom near the kill floor. The room had beige cinder-block walls and fluorescent overhead lighting. On the wall near the door hung two posters, one in English and the other in Somali, that read bringing beef to the people. The HR rep who was with us for most of those two days of orientation made sure we didn’t forget that mission. “Cargill is a worldwide organization,” she said before starting a lengthy PowerPoint presentation. “We pretty much feed the world. That’s why when the coronavirus started, we didn’t shut down. Because you guys want to eat, right?” Everyone nodded.

[Read: How the meat industry thinks about non-meat-eaters]

By that point, in early June, COVID-19 had forced at least 30 meatpacking plants across the United States to pause operations and, according to the Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting, had killed at least 74 workers. The Cargill plant reported its first case on April 13. Kansas public-health records reveal that over the course of 2020, more than 600 of the plant’s 2,530 employees contracted COVID-19. At least four died.

In March, the plant started to implement a series of social-distancing measures, including some that had been recommended by the CDC and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. It staggered breaks and installed plexiglass barriers on tables in the cafeteria and thick plastic curtains between workstations on the production line. During the third week of August, metal dividers suddenly appeared in the men’s bathrooms, providing workers with a bit of space (and privacy) at the stainless-steel urinal troughs.

The plant also hired a company called Examinetics to screen employees before each shift. In a white tent at the entrance to the plant, a team of medical personnel—all of whom wore N95 masks, white coveralls, and gloves—checked temperatures and handed out disposable face masks. Thermal cameras were set up inside the plant for additional temperature checks. Face coverings were mandatory. I always wore the disposable masks, but many other employees preferred to wear a blue neck gaiter with a United Food and Commercial Workers International Union logo or a black bandana with the Cargill logo and, for some reason, #extraordinary printed on it.

Catching the coronavirus wasn’t the only health risk at the plant. Meatpacking is notoriously dangerous. According to Human Rights Watch, government statistics show that from 2015 to 2018, a meat or poultry worker lost a body part or was sent to the hospital for in-patient treatment about every other day. On the first day of orientation, one of the other new hires, a Black man from Alabama, described a close call he’d had when he worked in packaging at National Beef’s plant up the road. He rolled up his right sleeve to reveal a four-inch scar on the outside of his elbow. “I almost turned into chocolate milk,” he said.

The HR rep told a similar story about a man whose sleeve got caught in a conveyor belt. “He lost his arm up to here,” she said, pointing halfway up her left biceps. She let this sink in for a few moments, before moving on to the next PowerPoint slide: “That’s a good transition into workplace violence.” She began explaining Cargill’s zero-tolerance policy on guns.

After a 15-minute break, we returned to the classroom for a presentation by a union rep.

“Why are we all here?” he asked.

“To make money,” someone responded.

“To make money!” the union rep repeated.

For the next hour and 15 minutes, money—and how the union helped us make more of it—was our focus. The union rep told us that UFCW’s local chapter had recently negotiated a permanent $2 raise for all hourly employees. He explained that all hourly employees would also earn an additional $6 an hour in “purpose pay,” because of the pandemic, through the end of August. This brought the starting wage up to $24.20. The next day at lunch, the man from Alabama told me how eager he was to work overtime. “Right now I’m trying to work on my credit,” he said. “We’ll be working so much, we won’t even have time to spend all that money.”

On my third day of work at the Cargill plant, the number of coronavirus cases in the U.S. surpassed 2 million. But the plant was beginning to bounce back from the outbreak that it had experienced earlier in the spring. (In early May, the plant’s production output had fallen by about 50 percent, according to a text message sent by Cargill’s director of state-government affairs to Kansas’s secretary of agriculture, which I later obtained through a public-records request.) The superintendent in charge of second shift, a giant man with a bushy white beard and a missing right thumb, sounded pleased. “It’s balls to the wall,” I overheard him say to contractors fixing a broken air conditioner. “Last week we were hitting 4,000 a day. This week we’ll probably be around 4,500.”

[From the November 2012 issue: Slaughterhouse rules]

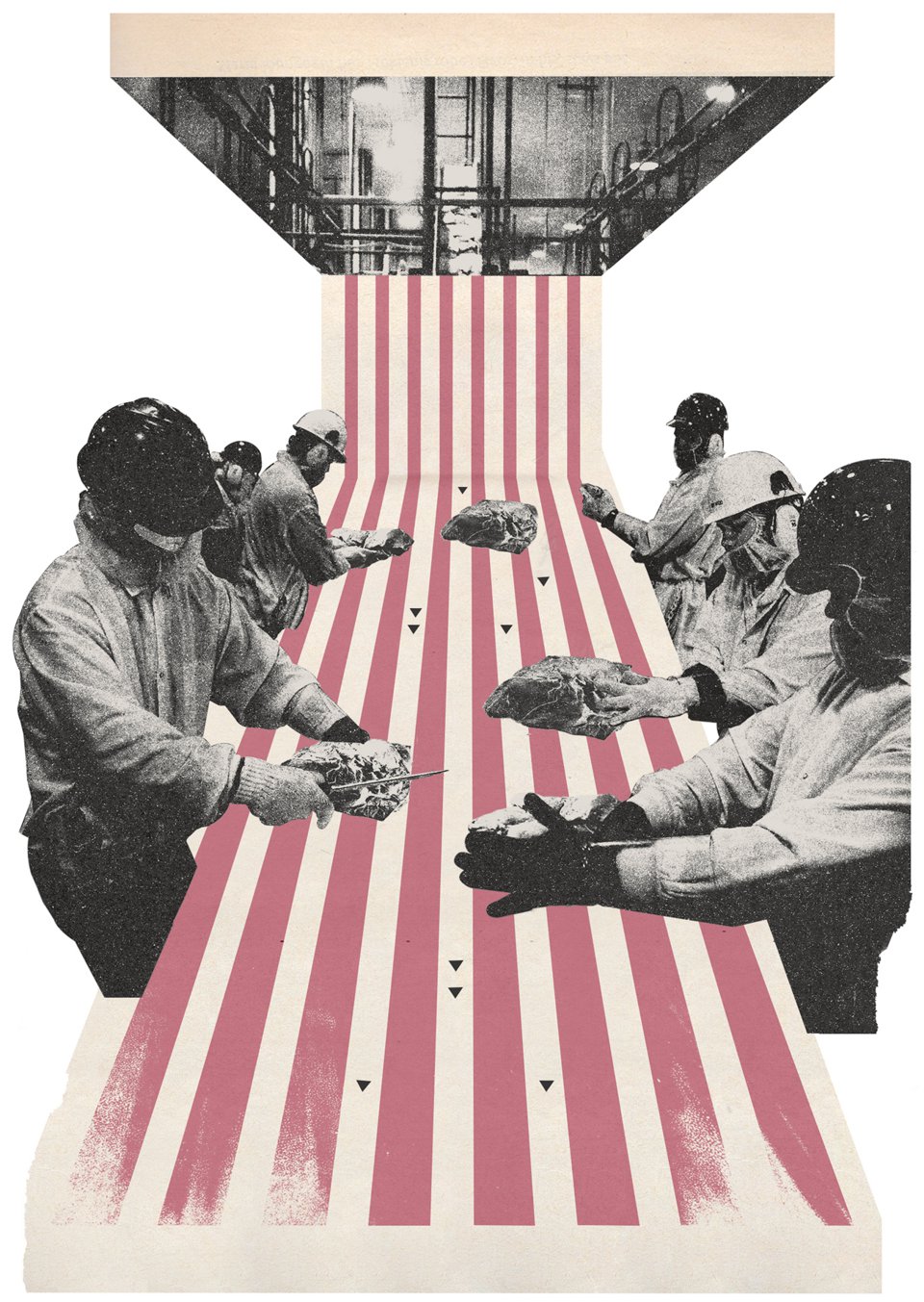

In fab, processing all of those cows takes place in a cavernous room filled with steel chains, hard-plastic conveyor belts, industrial-size vacuum sealers, and stacks of cardboard shipping boxes. But first is the cooler, where sides of beef are left to hang for an average of 36 hours after they leave the kill floor. When they are brought out for butchering, the sides are broken down into forequarters and hindquarters and then into smaller, marketable cuts of meat. These are what get vacuum-sealed and loaded into boxes for distribution. In non-pandemic times, an average of 40,000 boxes, each weighing between 10 and 90 pounds, are shipped out from the plant every day. McDonald’s and Taco Bell, Walmart and Kroger—they all buy beef from Cargill. The company has six beef-processing plants across the U.S.; the one in Dodge City is the largest.

The most important tenet of the meatpacking industry is “The chain never stops.” Companies do everything they can to ensure that their production lines keep moving as fast as possible. Yet delays do occur. Mechanical problems are the most common reason; less common are shutdowns initiated by USDA inspectors because of suspected contamination or “inhumane handling” incidents like the one that occurred two years ago at the Cargill plant. Individual workers help keep the line moving by “pulling count”—industry parlance for doing your share of the work. The surest way to lose the respect of your co-workers is to continually fall behind on count, because doing so invariably means more work for them. The most heated confrontations I witnessed on the line happened when someone was perceived to be slacking off. These fights never escalated into anything more than yelling or the occasional elbow jab. If things got out of hand, a foreman would be called over to mediate.

New hires have a probation period of 45 days in which to prove that they can pull count—to “qualify,” as it’s known at the Cargill plant. Each one is supervised by a trainer for the duration of that time. My trainer was 30, just a few months younger than me, and had smiling eyes and broad shoulders. He was a member of a persecuted ethnic minority from Myanmar, the Karen. His Karen name was Par Taw, but after becoming an American citizen in 2019, he changed his name to Billion. “Maybe I’ll be a billionaire one day,” he told me when I asked him how he had chosen his new name. He laughed, as if embarrassed by sharing this part of his American dream.

Billion was born in 1990 in a small village in eastern Myanmar. Karen rebels were in the middle of a long insurgency against the country’s central government. The conflict raged on into the new millennium—it is one of the longest-running civil wars in the world—and forced tens of thousands of Karen to flee over the border into Thailand. Billion was one of them. When he was 12 years old, he began living in a refugee camp there. He moved to the U.S. when he was 18 years old, first to Houston and then to Garden City, where he went to work at the nearby Tyson plant. In 2011, he landed a job at Cargill, where he has worked ever since. Like many Karen people who arrived before him in Garden City, Billion attends Grace Bible Church. It was there that he met Toe Kwee, whose English name is Dahlia. The two started dating in 2009. In 2016, they had their first son, Shine. They bought a house and got married two years later.

Billion was a patient teacher. He showed me how to put on a chain-mail tunic that looked made for a knight, layers of gloves, and a white-cotton frock. Later, he gave me an orange-handled steel hook and a plastic scabbard filled with three identical knives, each with a black handle and a slightly curved six-inch blade, and led me to an empty spot near the middle of a 60-foot-long conveyor belt. Billion slid a knife from the scabbard and demonstrated how to sharpen it using a counterweight sharpener. Then he got to work, trimming away cartilage and bone fragments and ripping off long, thin ligaments from boulder-size pieces of chuck moving past us on the belt.

Billion worked methodically as I stood behind him and watched. He told me that the key was to cut off as little meat as possible. (As a supervisor succinctly put it: “More meat, more money.”) Billion made the job look effortless. In one swift motion, he flipped over 30-pound slabs of chuck with the flick of his hook and pulled out ligaments from folds in the meat. “Take it slow,” he told me after we switched spots.

I cut into the next piece of chuck that came down the line, surprised by how easily my knife sliced through the chilled meat. Billion told me to sharpen my knife after every other piece. On my tenth or so piece, I accidentally hit the blade against the side of my hook. Billion motioned for me to stop working. “Be careful not to do that,” he said, the expression on his face telling me that I had made a cardinal mistake. Nothing is worse than trying to cut meat with a dull knife. I grabbed a new one from my scabbard and got back to work.

Looking back on my time at the plant, I consider myself lucky to have ended up in the nurse’s office only once. The precipitating incident occurred on my 11th day on the line. I was trying to flip over a piece of chuck when I lost my grip and drove the tip of my hook into the palm of my right hand. “It should heal in a few days,” the nurse said after she wrapped a bandage around the resulting half-inch-long gash. She told me that she often treated injuries like mine.

“I see at least one or two a day,” she said. “It’s why I have a job.”

“What’s the worst you’ve seen?” I asked.

“Guys losing a finger,” she said.

Over the next several weeks, Billion checked on me sporadically during my shifts, tapping me on the shoulder and asking, “Doing good, Mike?” before walking away. Other times he would linger to talk. If he saw that I was tired, he might grab a knife and work alongside me for a while. During one of these moments, I asked him if many people had been infected during the spring COVID‑19 outbreak. “Yeah, a ton,” he said. “I had it just a few weeks ago.”

Billion said that he’d likely caught the virus from someone in his carpool. Forced to quarantine at home for two weeks, Billion did his best to isolate himself from Shine and Dahlia, who was eight months pregnant at the time. He slept in the basement and rarely came upstairs. But during his second week of quarantine, Dahlia developed a fever and a cough. She started having difficulty breathing a few days later. Billion drove her to the hospital, where she was admitted and put on oxygen. Three days after that, a doctor induced labor. On May 23, she gave birth to a healthy baby boy. They named him Clever.

Billion told me all of this shortly before our 30-minute dinner break, which, along with our earlier 15-minute break, I had come to cherish. I had been working at the plant for three weeks by then, and my hands constantly throbbed with pain. When I woke in the mornings, my fingers were so stiff and swollen that I could hardly bend them. I took two ibuprofen tablets before work most days. If the pain persisted, I would take two more during one of my breaks. This was a relatively tame solution, I discovered. For many of my co-workers, oxycodone and hydrocodone were the painkillers of choice. (A Cargill spokesperson said that the company “is not aware of any trend in the plant” of illegal use of either drug.)

A typical shift last summer: I pull into the plant’s parking lot at 3:20 p.m. According to a digital bank sign that I passed on the way here, it’s 98 degrees outside. The windows of my car—a 2008 Kia Spectra with extensive hail damage and 180,000 miles on it—are rolled down on account of the air conditioner being broken. This means that when the wind blows from the southeast, I sometimes smell the plant before I see it.

I’m wearing an old cotton T-shirt, Levi’s jeans, wool socks, and Timberland steel-toed boots that I got for 15 percent off with my Cargill ID at a local shoe store. After I park, I put on my hairnet and hard hat and grab my lunch box and fleece jacket from the back seat. I walk past a holding pen on my way to the plant’s main entrance. Inside the pen are hundreds of cows waiting to be slaughtered. Seeing them alive like this makes my job harder, but I look at them anyway. Some jostle with their neighbors. Others crane their neck, as if they’re trying to see what’s ahead.

The cows fall out of view as I step into the medical tent for my health screening. When it’s my turn, a woman in full protective gear calls me over. She holds a thermometer to my forehead and hands me a face mask, while asking me a series of routine questions. When she tells me I’m good to go, I put on my mask, exit the tent, and pass through a turnstile and a security shack. The kill floor is to the left; fab is straight ahead, on the opposite side of the plant. On my way there, I walk past dozens of first-shift workers who are on their way out. They look tired and sore and grateful to be done for the day.

I make a brief stop in the cafeteria and take two ibuprofen. I put on my jacket and leave my lunch box on a wooden shelf. I then walk down a long hallway that leads to the production floor. I put in a pair of foam earplugs and pass through a swinging double door. The floor is a cacophony of industrial machinery. To help mute the noise and stave off boredom, employees can pay $45 for a pair of company-approved 3M noise-reduction earbuds, though the consensus is that they don’t drown out enough of the din to make listening to music possible. (Few seem to worry about the added distraction of listening to music while doing what is already an incredibly dangerous job.) One alternative is to buy a pair of non-approved Bluetooth earbuds that I could hide underneath a neck gaiter. I know a few guys who do this and have never been caught, but I decide not to risk it. I stick with the standard-issue earplugs, new pairs of which are handed out every Monday.

To get to my workstation, I climb up to a catwalk, then down a stairway that leads to a conveyor belt. The belt is one of a dozen that stretch across the middle of the production floor in long, parallel rows. Each row is called a “table,” and each table has a number. I work at table two: the chuck table. There are tables for shank, brisket, sirloin, round, and so on. The tables are one of the most crowded areas in the plant. At my spot on table two, I stand less than two feet away from the men who work on either side of me. The plastic curtains are supposed to help make up for the lack of social distancing, but most of my co-workers flip the curtains up and around the metal bars from which they hang. It’s easier to see what’s coming down the line this way, and before long I start doing the same thing. (Cargill denies that most workers flip up the curtains.)

At 3:42, I swipe my ID card at a time clock near my workstation. Employees have a five-minute window in which to clock in: 3:40 to 3:45. Any later and you lose half an attendance point (losing 12 points in a 12-month period can lead to termination). I walk to the front of the belt to get my equipment. I suit up at my workstation. I sharpen my knives and stretch my hands. A few of my co-workers fist-bump me as they walk by. I look across the table and watch two Mexican men standing next to each other make the sign of the cross. They do this at the start of every shift.

Pieces of chuck soon start coming down the belt, which on my side of the table moves from right to left. Ahead of me are seven chuck boners whose job it is to remove the bones from the meat. This is one of the hardest positions in fab (a grade eight, the highest grade of difficulty there is and five grades higher than chuck final trim, with a wage increase of $6 an hour). The job requires both careful precision and brute strength: careful precision for cutting as close to the bones as possible, and brute strength for prying them out. My job is to trim off whatever pieces of bone and ligament the chuck boners miss. This is what I do for the next nine hours, stopping only for my 15-minute break at 6:20 and 30-minute dinner break at 9:20. “Not too much!” my supervisor yells when he catches me cutting off too much meat. “Money! Money! Money!”

Toward the end of the shift, a palpable restlessness sets in across the floor. The line slows down and everyone keeps glancing over at the cooler, waiting for the last side of beef to come down the chain. I make eye contact with the shorter of the two Mexican men who made the sign of the cross. He gives me a thumbs-up, tilts his head to the side, and shrugs his shoulders. Translation: You doing all right? I nod my head and return the thumbs-up. He points to an invisible watch on his wrist and holds his index finger and thumb half an inch apart. Hang in there. The shift is almost over. He then mimes opening a can of beer. He tilts his head back and takes a swig. He nods a satisfied nod, makes a pillow with his hands, and rests the side of his head against it with his eyes closed. When he opens them and lifts his head, I nod approvingly and give him another thumbs-up.

A few minutes later, one of the chuck boners bangs the edge of the belt with the handle of his hook. He does this every night to announce that the last side of beef has left the cooler. I hurriedly trim the last piece of chuck as soon as it reaches me. I put away my equipment and clock out at 12:43. I’m tired and sore and grateful to be done for the day. When I get back to my apartment, I grab a beer and drink it on the balcony. Across the street is a small pasture. I usually see a dozen or more cattle there during the day, but in the dark they are impossible to spot. Not that I mind. The last thing I want to see right now is a cow.

My job on the chuck table turned out to be much more difficult than I had anticipated. The sheer volume of meat that came down the line could be overwhelming at times; more than once, I threw my hands up in defeat.

A month or so in, things started to improve. My hands were still sore most days, as were my shoulders. (In mid-August, my left ring finger would develop an annoying habit of spontaneously locking up so I couldn’t extend it—a condition known as “trigger finger.”) But at least the constant, throbbing pain had begun to relent. And now that my hands were stronger, I was getting better at the job. By the Fourth of July, I was close enough to pulling count that Billion told me I qualified. On my 20th day on the line, he drew me aside to sign some paperwork that made it official. He later gave me a white hard hat to replace the brown one that I had received during orientation. I was surprised by how excited I was to put it on.

A part of me had hoped that qualifying was all I needed to do to fit in with my co-workers. Yet some of them had suspicions about me that my new hard hat did nothing to allay. My skin color alone was enough to raise eyebrows. Of the 30 or so men who worked on the chuck table, I was one of only two white Americans. Most of the other men were from Mexico; others were from El Salvador, Cuba, Somalia, Sudan, and Myanmar. When anyone asked how I’d ended up working at the plant, my usual approach was to explain, truthfully, that I had been traveling in Asia when the pandemic hit and, after flying home, wanted a quick way to make money. I didn’t tell anyone that I was a journalist, though a Mexican American chuck boner who worked next to me came close to figuring it out.

“You aren’t an undercover boss, are you?” he asked me late one shift.

“Why would you think that?” I asked.

“In the four years that I’ve worked here,” he said, “I’ve never seen another white guy do your job.”

[Read: Why it’s immigrants who pack your meat]

Most of the men eventually got used to my presence on the line. Even the skeptical chuck boner warmed up to me. As time went on, he would turn to me to talk about his latest marital drama or to ask questions about traveling abroad. “Have you had McDonald’s over there?” he once asked me about Singapore. I told him that I had. He told me that he dreamed of traveling abroad someday but that for now he needed to work to support his wife and two young children. He was 24 years old, and he told me that he planned to work at the plant until he could retire. “I got my 401(k) here and everything,” he said, in a tone that suggested a kind of forced acceptance.

“If you could do any job in the world, what would you want to do?” I once asked.

“Lots of shit,” he said, his eyes wide.

“What’s your No. 1?”

He thought for a few seconds and looked up at the ceiling. “Own something like this,” he said.

My conversations with the chuck boner were a welcome distraction from the monotony of my job. Another thing that helped was an unspoken agreement I had with the friendly Mexican man who worked to my left. If one of us walked away from the line to check the nearby time clock—something we both did at least once a shift—we would report back to the other one by using the butt of our knives to carve the time into the thin layer of pink juices that coated the conveyor belt. It was a simple act of solidarity, one that meant more to me as the weeks passed. Though I often felt a profound sense of alienation on the line, I never once felt alone.

Working second shift, especially amid a pandemic, made it virtually impossible to spend time with my co-workers outside the plant. Every bar in Dodge City closes by 2 a.m. This meant that if I ever wanted to brave the risk of infection to go out for drinks after work, I would have no more than an hour before last call. But one evening in September, Billion asked me if I had any plans for the weekend. I told him that I didn’t. “Tomorrow after work I’m going frog hunting with my brother-in-law,” he said. “You wanna come?”

The next night after clocking out, I met Billion in the cafeteria and walked with him to the parking lot, where his brother-in-law sat waiting for us in a black Toyota Camry. I got in my car and followed the two men to a small lake 20 miles north of the plant. We passed endless fields of corn and hundreds of wind turbines, their red warning lights flashing in hypnotic unison across a moonless sky. As Billion later explained to me, the new moon was key to helping us avoid casting shadows over the easily spooked bullfrogs. The problem was the wind, which rustled the prairie grass that encircled the lake and made it difficult to hear their calls.

When we arrived at the lake, Billion introduced me to his brother-in-law, Leo, who was 20 years old. “Do you recognize him?” Billion asked. “He used to work on table three.” I didn’t, and Leo explained that he had worked there for only two and a half weeks before switching to the Tyson plant near Garden City, where he lives. “I got tired of the drive,” he said. Billion opened the trunk of his car and reached inside for three flashlights and an empty burlap sack. These were our hunting supplies. I asked what I needed to do. “Just follow me,” Billion said, before heading down a trampled path through the prairie grass and onto the lake’s muddy bank.

Before long, Billion spotted a frog at the edge of the water. To catch it, he first stunned it by shining his flashlight directly into its eyes. He then crept up next to it in a crouch, slowly positioned his hand over its torso like the crane of an arcade claw machine, and snatched it off the ground. The frog was about the size of a pint glass, and Billion held it so tightly that its eyes bulged out of their sockets. Rather than kill it, he left it alive and broke its hind legs. “So it can’t get away,” he said. I watched him drop the maimed frog into the burlap sack, which Leo held with outstretched arms.

For the next two hours, we slowly made our way around the lake. Billion walked in front and caught most of the frogs, about 20 in total. I caught only four. I thought that together we had a good haul, but Billion and Leo were disappointed. “Someone else must have been out here already,” Billion said, pointing down at a pair of fresh shoe prints. Perhaps it was someone from the small community of Karen people in Garden City. Leo said that everyone in the community knew about the lake and had been hunting frogs there for years.

We didn’t call it a night until sometime after 3 o’clock. On the way back to our cars, Billion talked excitedly about the spicy frog curry he planned to cook for dinner the next day. It was one of his specialties, something he had learned to make in the refugee camp. “Frog is the only meat that we can eat fresh here,” he said. “It’s better than chicken.”

At some point in early July, the TVs in the cafeteria at the plant switched from showing the Wichita Fox affiliate to showing Fox News. Seeing the chyrons on Laura Ingraham’s show in place of the local 9 o’clock news was a stark change—“Trump: I will bring law and order, Biden won’t”; “Trump’s America first vs Biden’s America last”; “Biden beholden to billionaires and Bolsheviks”; “Biden’s COVID plan: blindly following the ‘experts.’ ”

The night before the election, Fox News was broadcasting live from Kenosha, Wisconsin, at one of Donald Trump’s final campaign rallies. During my dinner break, I watched a Haitian-born man in his mid-30s stop underneath one of the TVs on his way back to the floor. When the camera zoomed in on Trump, the man held up both his middle fingers toward the screen. He did this for about half a minute without saying a word. Then he yelled, “I’m voting for Biden!” as he walked away. It was the most overt act of political expression I witnessed at the plant. The only other thing that came close was some pro-Trump graffiti scrawled anonymously on the inside of a bathroom stall: america love it or leave it and trump 2020. The latter got a couple of responses: fok you and chinga tu madre.

Mostly what I found at the plant was a pervasive sense of political apathy. Many people I talked with in the weeks leading up to November 3 told me the results hardly mattered to them. “As long as they leave me alone, I don’t care who wins,” a Mexican American man told me over dinner in late October. “The government hasn’t done anything for me.” It seemed clear that he didn’t plan to vote.

On Election Day, I drove to a polling station south of downtown. At a stone-and-concrete band shell by the voting pavilion, I met an older white man who was happy to share his opinion on almost anything. The man said that he had voted for Trump, that China needed to pay for starting the pandemic, and that he didn’t have a problem with immigrants as long as they came here legally. “If they ever leave,” he said, referring to those who worked in the local meatpacking plants, “we’d be in a world of hurt.” The man knew how important immigrants were to Dodge City’s economy, but he showed little interest in getting to know them personally. “It’s like oil and water,” he said. “We don’t really get together … I guess they’re scared of us.”

After leaving the band shell, I drove to a liquor store up the street from my apartment. I knew that it was going to be a long week. While I was browsing the whiskey shelves, the store owner came over to offer a few recommendations. “They say if you take a shot of whiskey that is 80-proof or higher a day it will help protect you against the coronavirus,” she said as she reached for a bottle of 90-proof Woodford Reserve. “The virus likes to lodge in your throat, and the whiskey will help keep your throat clear. I don’t know if it’s true, but I did it religiously over the summer. Then I went to Florida and I was fine.” I looked at her incredulously—then went for something even stronger, splurging on a bottle of 114-proof Willett.

I arrived at work an hour before the start of my shift to see if there was finally any buzz about the election. I sat outside and talked with a middle-aged Somali man. “I voted for Trump,” he said. He was both Muslim and a former refugee—not typical of Trump supporters as I imagined them. “He’s good at business,” he said when I asked him what he liked about Trump.

As Election Day turned into Election Week, I heard dozens of stories from nonwhite workers who wanted Trump to win. A Congolese man told me that he liked Trump because he “makes everything good.” “Trump takes care of the world,” a Salvadoran man said. “If Biden wins, I think ISIS will be happy.” Then there was the man from Sudan who said that he, too, admired Trump’s business credentials before leaning in to tell me why else he liked him. “Trump doesn’t want people from Arab countries to come to America,” he whispered. “I think that’s good.”

[Read: How meat producers have influenced nutrition guidelines for decades]

I did also meet people at the plant who supported Joe Biden, many of them because they couldn’t stand Trump. “He’s crazy” was the most common sentiment expressed by those who wanted Trump to lose. No worker I spoke with was more invested in the election outcome than the Haitian man who had flipped off the TV. “You know why I don’t like Trump?” he asked me during our 15-minute break one night. “Because he knew about the coronavirus and didn’t do anything about it. We need a president who will protect us. So many people have died because of him.” The man paced back and forth while he talked. He paused for a moment to check an Electoral College map that he had pulled up on his phone. “Trump doesn’t give a shit about us,” he concluded.

On the Saturday the election was called for Biden, I went into work. During the shift change that afternoon, I noticed few signs of celebration or disappointment.

The Mexican American man I’d eaten dinner with a couple of weeks earlier came over to my table. He was carrying a large styrofoam cup of coffee and a bag of Bimbo puff pastries. He smelled of marijuana. As he sat down at an adjacent table, a white pill fell out of his pants pocket and onto the floor. He reached down to pick it up. “I’m telling you, Michael,” he said. “This is my life.” He said that for the past week he had felt an excruciating pain in his left arm and shoulder. He couldn’t see a doctor until January because his health-insurance coverage didn’t start until then, so for now he was self-medicating with hydrocodone. I didn’t ask where he’d gotten it. “I’m going to ask for oxycodone when I go to the doctor,” he said. “I need something more powerful.” I decided not to ask him about the election. He had more important things to worry about.

On the Monday after the election, the news reported that the U.S. had surpassed 10 million coronavirus cases, and Pfizer-BioNTech announced that early data showed their vaccine was more than 90 percent effective. In Kansas, the virus was raging out of control. New cases were hitting record numbers, hospitals were strained for resources, and deaths were on the rise. At the plant, additional plexiglass barriers were installed on the tables in the cafeteria, splitting them into quarters instead of halves. Department holiday parties were canceled. And everyone who didn’t already have a plastic face shield was given one to attach to their hard hat. Wearing them was mandatory. But many people, including me, didn’t pull them down all the way, because of how easily they fogged up from the masks that we still had to wear. The supervisors didn’t seem to care; many of them did the same thing.

My last shift at the plant was the night before Thanksgiving, some six months after I’d started. The work itself had become muscle memory, and I spent much of the night lost in thought. At 12:45, I clocked out for the last time. “Nothing we can do to convince you to stay, help us out a bit longer?” one of the foremen asked me when I approached him to turn in my ID badge. I told him that I really couldn’t, that I had to get back to Topeka. “Let us know if you want to come back,” he said. “The door is always open.” I didn’t doubt that, but I knew that I would likely never step foot inside the plant again.

Outside, the night air was frigid. Across the way, hundreds of 53-foot refrigerated trailers sat in neat rows, waiting to be loaded with beef before being hauled away. I wish I could say that, in the early hours of Thanksgiving morning, the trailers put me in mind of American gluttony and abundance—our insatiable and unsustainable craving for meat. But as I walked to my car, all that came to mind were photos I had seen of identical trailers, mobile morgues, parked outside hospitals across the country.

A couple of weeks after I left the plant, I drove to Garden City to visit Billion and his family. I met them at a small Vietnamese restaurant and then followed them to the local zoo. It was an unseasonably warm day, and the mid-afternoon sun was melting what little snow remained from a recent winter storm. The lemurs seemed especially happy about this. Billion lifted Shine onto his shoulders to give him a better view, while Dahlia kept an eye on Clever in his stroller. Dahlia was four months pregnant. Billion was hoping for a girl; Dahlia didn’t have a preference. She just wanted the pregnancy to go better than her last one.

I usually don’t care much for zoos. I find them depressing, largely because my childhood zoo, in Topeka, has a long and troubling animal-safety record. (In 2006, a hippopotamus died there, hours after being found in 108-degree water.) But after working in a meatpacking plant, I found it comforting to see so many animals that were still alive, even if they were in cages. Seeing them with a 5-year-old made the experience all the more enjoyable. When Shine wasn’t perched on Billion’s shoulders, he was sprinting ahead to the next exhibit and shouting out each animal he saw. “Rhino!” “Giraffe!” “Fox!” “Lions!” He was in awe of the animals, which made me wonder what he knew about where his dad worked.

As we made our way past the antelope exhibit, I asked Billion and Dahlia how they had chosen their sons’ names. Shine had been Dahlia’s idea. “I want him to shine brightly,” she said. Billion had picked Clever with more concrete aspirations in mind. “I want him to be smart and do well in school,” he said. “Maybe he’ll become a doctor or a lawyer someday.” Whatever they grew up to be, Billion would never allow them to work in a meatpacking plant. That was something only he did. “I do it for them,” he told me. They were what made his work essential.

This article appears in the July/August 2021 print edition with the headline “Pulling Count.”

What's Your Reaction?