Seven Books That Will Change How You Watch the Olympics

These titles will allow you to view the competition with a new appreciation.

This week, 11 million tourists will join more than 10,000 athletes from 206 countries for the 2024 Summer Olympics. Fifty-nine percent of American adults say they plan to tune in to the Games. This is a level of attention that the founders of the modern Olympics could only have dreamed of achieving. The Games didn’t debut to much fanfare: When a Harvard track athlete tried to get permission to compete in the first modern edition, in 1896, a skeptical dean accused him of wanting “to go to Athens on a junket.” Even the well-known phrases Olympic record and Olympic champion didn’t enter the popular lexicon until the 1920s.

During the 20th century, the Olympic Games quickly transformed from little-known curiosities to major, world-altering events. While writing my book, The Other Olympians: Fascism, Queerness, and the Making of Modern Sports, I was struck by how much the Games have shaped contemporary life and politics. These maddening, wondrous competitions have been the site of terrorism and protest, triumph and perseverance, political victory and corruption, and have influenced which states we count as countries and which cities become tourism hubs.

Understanding the Games’ spasmodic path to their current place in the monoculture, and their immense power, allows you to watch these sports with a new appreciation for the backroom decisions that make them possible. Here are seven essential books to complement your viewing.

Dreamers and Schemers: How an Improbable Bid for the 1932 Olympics Transformed Los Angeles From Dusty Outpost to Global Metropolis, by Barry Siegel

On paper, the first Olympics in Los Angeles, held in 1932, probably shouldn’t have happened. In the 1920s and early ’30s, the city was seedy and unstable, rife with political corruption and mysterious deaths, and had little worldwide reputation. Most inauspiciously, the Games unfolded during the height of the Great Depression. When the state of California decided to subsidize some of the event’s costs amid mass unemployment, workers protested with signs that read Groceries Not Games! Olympics Are Outrageous! But somehow, everything clicked into place. Siegel chronicles the making of this Olympics—and, really, the making of this city—in impressively sequenced detail, focusing on the behind-the-scenes corralling that persuaded, for instance, Hollywood actors such as Joan Crawford, Norma Shearer, Charlie Chaplin, and Clara Bow to show up to events. Meanwhile, studios hosted lunches and an exclusive beach-house party, and 30,000 palm trees were planted across the city to give it the air of paradise. By the closing ceremonies, Los Angeles had a new halo. The Olympics had proved—for the first time, but not the last—that wherever they went, the eyes of the world followed.

The Games Must Go On: Avery Brundage and the Olympic Movement, by Allen Guttmann

The modern Olympics are hard to understand without first understanding Avery Brundage, an American athlete, a Chicago real-estate developer, and, later, president of the International Olympic Committee. His style was brash: He wasn’t afraid to ban a top competitor, or to wave away the need for women’s sports. But, as Guttmann argues in his definitive biography of this morally complicated man, perhaps no one shaped the governance of the Olympics more. Brundage helped turn the Olympics—once a clubby, largely European affair—into a truly global institution. He was an early advocate of expansion, pushing for a Japan-hosted Olympics in 1940 (though those Games were canceled because of the war). He helped persuade the U.S.S.R. to participate for the first time, instituted the first anti-doping controls, and cemented the sex-testing policies that would shape who was allowed to compete in women’s sports for decades to come. Brundage also solidified the IOC’s generally agnostic relationship with world politics. He saw no issue with allowing the Nazis to host the Olympics in 1936, writing that the Olympics must not get involved in politics. Years later, as leader of the IOC, Brundage stuck to those beliefs: In the 1960s, after the United Nations tried to ban apartheid South Africa from competing, Brundage pushed to allow the country to participate anyway. Guttmann untangles Brundage’s many failures all while acknowledging that, for better or worse, he is the reason the Olympic Games exist as they do today.

[Read: How skateboarding at the Olympics stayed rebellious]

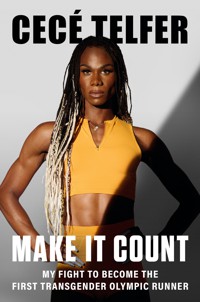

Make It Count, by CeCé Telfer

If not for a new eligibility policy, CeCé Telfer—a Jamaica-born hurdler and former college athlete who won the NCAA title in the 400 meters in 2019—might be competing in Paris this year. In her new memoir, Telfer, who is trans, chronicles her rise through track-and-field sports, including her repeated, grueling efforts to try out for the Olympics. While she was readying herself for Tokyo in 2021, Telfer struggled with homelessness, and picked up extra shifts at her nursing-home job. She needed money, she needed to train, and she needed to meet with doctors to ensure she was keeping her hormone levels within the range required at the time for trans women to compete—“I never get a break,” she writes of the period. Yet the day before she was supposed to fly to Oregon for the Olympic trials, she was notified that she needed to submit additional documentation—therapy notes, more hormone tests, reformatted blood work—only to then be barred from running by USA Track & Field that night. Devastated, Telfer turned her attention to the Paris Olympics. Then, in early 2023, she got word that World Athletics, the governing body for track-and-field sports, had changed its standard. Now trans women are essentially banned from the Olympics. Telfer’s memoir focuses on her personal journey, and spends much time on her hopes, dreams, and years of assiduous training, but many of the scenes she describes—such as waiting for the global federation to release its new policy, her future hanging on the wording of one subjectively written statement—underscore the very human ramifications of Olympic bureaucracy.

Power Games: A Political History of the Olympics, by Jules Boykoff

The televised spectacle of the Olympics tends to hide some of the Games’ most crucial logistics: who gets to compete, which countries are allowed to host or send teams, and even which workers built the stadiums. Boykoff brings this secret side of the Olympics to life in Power Games, a masterful chronicle of the bureaucracy behind the event. Boykoff starts with Pierre de Coubertin, the French baron who jump-started the Olympics in 1896 and who saw them as, almost exclusively, a venue for white men; he then takes readers on a wild jaunt through administrative history. We meet officials such as Avery Brundage, of course, as well as Alice Milliat, a stenographer who created her own rival to the Olympics called the Women’s World Games. Boykoff is particularly sharp when discussing the activists who have rallied against the Olympics. When Denver was awarded the 1976 Winter edition, for instance, locals staged letter-writing campaigns arguing that the Games would have a devastating ecological impact. They succeeded in securing a ballot referendum against using public money for the event—and they won. Without subsidies to keep it in Denver, 1976’s Games were moved to Innsbruck, Austria, instead. Those stories feel particularly resonant as the NOlympics movement to cancel the Olympics gains steam in Los Angeles, the 2028 host.

[Read: The Olympics have lost their appeal]

Triumph: The Untold Story of Jesse Owens and Hitler’s Olympics, by Jeremy Schaap

Born in Alabama in 1913 to a family of sharecroppers, Jesse Owens ran track in an era when the world’s top runners were athletic celebrities on par with the titans of football and baseball, Schaap writes. Sports officials—almost all of whom were white men—doubted Owens at every turn. They were, of course, dead wrong: At the 1936 Berlin Games, Owens took home four gold medals. Perhaps the most fascinating thread in Triumph, however, centers on Owens’s conflicted relationship with that year’s Olympics. In the U.S., competing in an event that might burnish the reputation of the Nazis was controversial, and anti-fascist activists organized a massive boycott of the Games. Many American sports officials wanted Owens to come out against the protest; NAACP Secretary Walter White urged him to support it. Owens, who personally knew the depths of America’s anti-Black racism, was torn. At one point, he signed a letter supporting the Olympics. Then, in a radio interview, he seemed leery: “If there is discrimination against minorities in Germany, then we must withdraw.” It was a weighty quandary to place on a 22-year-old athlete, and it hasn’t gone away. Today, young Palestinian and South Sudanese athletes, for instance, carry the weight of competing at an elite level while also calling attention to what their communities are facing.

Serving Herself: The Life and Times of Althea Gibson, by Ashley Brown

In 1983, a writer met with one of the most famous tennis players of her generation: Althea Gibson, the winner of 11 Grand Slam titles in the 1950s and the first Black woman to win a Grand Slam event. But Gibson, now nearly 60, was still struggling to make ends meet. How did this happen? In this remarkable biography, Brown presents a compelling answer: Gibson was living out “the consequences of having never fit neatly into society when she was younger.” In the ’50s, Gibson was often the only Black woman on the court, and she struggled to afford expensive rackets and clothes. She frequently dealt with racism and misogyny, in person and in the press: Reporters called her “arrogant,” “non-cooperative,” and “ungracious.” Magazines criticized her as insufficiently feminine, photographing her to accentuate her muscles. Few brands were willing to sponsor her. As an amateur athlete until shortly before her retirement, she also couldn’t collect money from her sport. This richly detailed biography cements Gibson as one of the most important athletes of the 20th century, while exploring what happens after a star leaves the spotlight.

[Read: A century ago, the Paris 1924 Summer Olympics]

Mind Game: An Inside Look at the Mental Health Playbook of Elite Athletes, by Julie Kliegman

At the Tokyo Olympics in 2021, when Simone Biles pulled out of several of her events because she had the “twisties”—a phenomenon where gymnasts lose track of themselves in the air—she opened up a wide-ranging conversation about mental health in sports. That conversation, the journalist Kliegman writes in Mind Game, was at least a century in the making: Exactly 100 years before Biles’s decision, Babe Ruth sat for psychological tests at Columbia University. Sports psychology is an old field, but it had its share of fits and starts, as Kliegman documents in her book. Perhaps most strikingly, the baseball team the St. Louis Browns hired a hypnotist named David F. Tracy in 1950 to improve the performance of its players. For decades, officials hardly took seriously the mental health of their elite athletes; tellingly, doctors who had trained in psychology rather than exercise science didn’t start working for sports teams and leagues until the 1980s. Only in the past 10 years or so have leagues and the public really seemed ready to have a conversation about the intense toll that competing in front of the world can take on a person’s psyche. When an athlete steps into the spotlight, you will, after reading Mind Game, have a small window into what they might be feeling and how they handle that pressure.

What's Your Reaction?