Rachel Cusk’s Lonely Experiment

First she abandoned plot in her fiction; now characters must go.

Start, as one tends to do in Rachel Cusk’s writing, with a house. It is not yours, but instead a farmhouse on the island property to which you have come as a renting vacationer. It has no obvious front door, and how you enter it, or whether you are welcome to do so, isn’t clear. You are, after all, only a visitor. Built out in haphazard fashion, the house seems both neglected and fussed over, and as a result slightly mad. A small door, once located, opens to reveal two rooms. The first, although generously proportioned and well lit, shocks you with its disorder, the riotous and yet deadening clutter of a hoarder. As you navigate carefully through it, the sound of women’s voices leads you to a second room. It is the kitchen, where the owner’s wife, a young girl, and an old woman—three generations of female labor—prepare food in a clean and functional space. When you enter, they fall silent and seem to share a secret. They consent to rather than encourage your presence, but here you will be fed. Of the first room, the owner’s wife comments dryly that it is her husband’s: “I’m not allowed to interfere with anything here.”

This is a moment from Parade, Cusk’s new book, and like so much in this novel of elusive vignettes, it can be seen as an allegory about both fiction and the gendered shapes of selfhood. After reading Parade, you might be tempted to imagine the history of the novel as a cyclical battle between accumulation and erasure, or hoarders and cleaners. For the hoarders, the ethos is to capture as much life as possible: objects, atmospheres, ideologies, social types and conventions, the habits and habitudes of selves. For the cleaners, all of that detail leaves us no space to move or breathe. The hoarder novel may preserve, but the cleaner novel liberates. And that labor of cleaning, of revealing the bare surfaces under the accumulated clutter of our lives and opening up space for creation and nourishment, is women’s work. Or so Cusk’s allegory invites us to feel.

Whether or not the typology of hoarder and cleaner is useful in general, it has licensed Cusk to push her style toward ever greater spareness. For the past decade, since 2014’s Outline, Cusk has been clearing a path unlike any other in English-language fiction, one that seems to follow a rigorous internal logic about the confinements of genre and gender alike. That logic, now her signature, has been one of purgation. The trilogy that Outline inaugurated (followed by Transit and Kudos) scrubbed away plot to foreground pitiless observation of how we represent, justify, and unwittingly betray ourselves to others. Each of these lauded novels is a gallery of human types in which the writer-narrator, Faye, wanders; finding herself the recipient of other people’s talkative unburdening, she simply notices—a noticing that, in its acuity and gift for condensed expression, is anything but simple. Cusk’s follow-up, 2021’s Second Place, is a psychodrama about artistic production that sacrifices realistic world making for the starkness of fable.

[Read: Has Rachel Cusk reached the limits of the English sentence?]

Now, in Parade, the element to be swept away is character itself. Gustave Flaubert once notoriously commented that he wanted to write “a book about nothing”; Cusk wants to write a book about no one. No more identities, no more social roles, even no more imperatives of the body—a clearing of the ground that has, as Cusk insists, particular urgency for writing by women, who have always had to confront the limits to their autonomy in their quests to think and create. The question Parade poses is what, after such drastic removal, is left standing.

If this sounds abstract, it should—Cusk’s aim is abstraction itself. Parade sets out to go beyond the novel’s habitual concretion, to undo our attachment to the stability of selfhood and its social markers. We are caught by our familiar impulses; trapped within social and familial patterns and scripts; compelled, repelled, or both by the stories of how we came to be. What if one didn’t hear oneself, nauseatingly, in everything one said and did, but instead heard something alien and new? This is Cusk’s negative theology of the self, a desire to imagine lives perfectly unconditioned and undetermined, no longer shaped by history, culture, or even psychological continuity—and therefore free from loss, and from loss’s twin, progress. It is a radical program, and a solitary one.

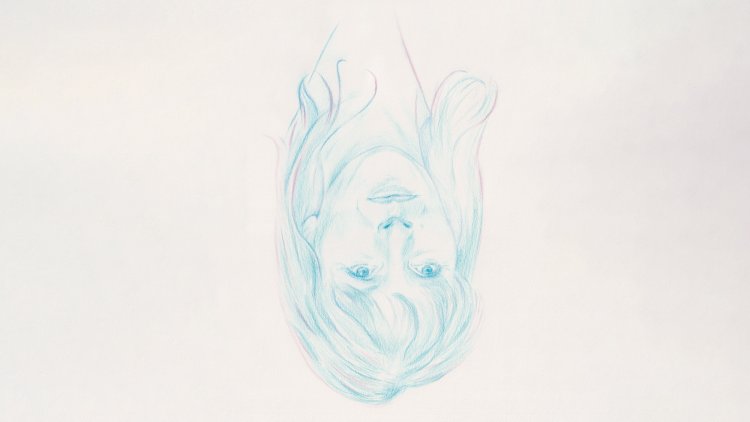

To be concrete for a moment: The book comes in four titled units. Its strands are not so much nested as layered, peeling apart in one’s hands like something delicate and brittle. What binds them together is the recurring appearance of an artist named “G,” who is transformed in each part, sometimes taking multiple forms in the same unit. G can be male or female, alive or dead, in the foreground or the background, but G always, tellingly, gravitates toward visual forms rather than literary forms: Parade is in love with the promise of freedom from narrative and from causality that is offered by visual representation. We remain outside G, observing the figure from various distances, never with the intimacy of an “I” speaking to us. G is sometimes tethered to the history of art: Parade begins by describing G creating upside-down paintings (a clear reference to the work of Georg Baselitz, though he goes unnamed); a later G is palpably derived from Louise Bourgeois, the subject of an exhibition that figures in two different moments in the novel. Yet G tends to float free of these tethers, which threaten to specify what Cusk prefers to render abstractly.

[From the January/February 2017 issue: Rachel Cusk remakes her fiction in Transit]

Cusk imagines a series of scenarios for G, often as the maker of artworks viewed and discussed by others with alarm, admiration, or blasé art-world sophistication. When the shape-shifting G moves into the foreground, shards of personal life surface. As a male painter, G makes nude portraits of his wife that lurch into grotesquerie, imprisoning her while gaining him fame. As a female painter, she finds herself, as if by some kind of dark magic, encumbered with a husband and child. Another G abandons fiction for filmmaking, refusing the knowingness of language for the unselved innocence of the camera: “He wanted simply to record.” Whatever changes in each avatar—G’s gender; G’s historical moment; whether we share G’s thoughts, see G through their intimates, or merely stand in front of G’s work—the differences evaporate in the dry atmosphere that prevails in Parade. G, whoever the figure is, wants to disencumber their art of selfhood. So we get not stories but fragmented capsule biographies, written with an uncanny, beyond-the-grave neutrality, each of them capturing a person untying themselves from the world, casting off jobs, lovers, families.

People on their way out of their selves: This is what interests Cusk. From a man named Thomas who has just resigned his teaching job, putting at risk his family finances as well as his wife’s occupation as a poet, we hear this: “I seem to be doing a lot of things these days that are out of character. I am perhaps coming out of character, he said, like an actor does.” The tone is limpid, alienated from itself. “I don’t know what I will do or what I will be. For the first time in my life I am free.” Free not just from the story, but even from the sound of himself, the Thomasness of Thomas.

Parade’s hollowed-out figures have the sober, disembodied grace of someone who, emerging from a purification ritual, awaits a promised epiphany. The female painter G, having left behind her daughter with a father whose sexualized photographs of the daughter once lined the rooms of their home, is herself left behind, sitting alone in the dark of her studio: This is as far as Cusk will bring her. They’ve departed, these people, been purged and shorn, but have not yet arrived anywhere, and they stretch out their hands in longing for the far shore and lapse into an austere, between-worlds silence. Cusk observes an even more disciplined tact than she did in Outline. If regret lurks in their escapes—about time wasted, people discarded, uncertainty to come—Cusk won’t indulge it. She seems to be not describing her figures so much as joining them, sharing their desire, a kind of hunger for unreality, a yearning for the empty, unmappable spaces outside identity. The result is an intensified asceticism. Her sentences are as precise as always, but stingless, the edges of irony sanded down.

What Cusk has relinquished, as if in a kind of penance, is her curiosity. Even at its most austere, her previous work displayed a fascination with the experience of encountering others. That desire was not always distinguishable from gossip, and certainly not free of judgment, but was expressed in an openness to the eccentricities of others as a source of danger, delight, and revelation. These encounters appealed to a reader’s pleasure in both the teasing mystery of others and the ways they become knowable. In Parade, Cusk seems to find this former curiosity more than a little vulgar, too invested in what she calls here “the pathos of identity.”

Nothing illustrates this new flatness better than “The Diver,” Parade’s third section. A group of well-connected art-world people—a museum director, a biographer, a curator, an array of scholars—gathers for dinner in an unnamed German city after the first day of a major retrospective exhibition of the Louise Bourgeois–like G. The opening has been spoiled, however, by an incident: A man has committed suicide in the exhibition’s galleries by jumping from an atrium walkway. (It is one of the novel’s very few incidents, and it occurs discreetly offstage.) The diners collect their thoughts after their derailed day, ruminating on the connections between the suicide and the art amid which it took place, on the urge to leap out of our self-imposed restraints—out of our very embodiment.

Their conversation is detached, a bit stunned, but nonetheless expansive: These are practiced, professional talkers. The scene is also strangely colorless. In discussing the hunger to lose an identity, each speaker has already been divested of their own, and the result is a language that sounds closer to the textureless theory-Esperanto of museum wall text. The director weighs in: “Some of G’s pieces, she said, also utilise this quality of suspension in achieving disembodiment, which for me at times seems the furthest one can go in representing the body itself.” Someone else takes a turn: “The struggle, he said, which is sometimes a direct combat, between the search for completeness and the desire to create art therefore becomes a core part of the artist’s development.”

It is politely distanced, this after-suicide dinner in its barely specified upper-bourgeois setting, and all of the guests are very like-minded. The interlude generates no friction of moral evaluation and conveys no satiric view of the quietly distressed, professionally established figures who theorize about art and death. What one misses here is the constitutive irony of the Outline trilogy, the sense that these people might be giving themselves away to our prurient eyes and ears. One wants to ask any of Parade’s figures what anguish or panic or rage lies behind their desire to cease being a person—what struggle got them here.

If Parade feels too pallid to hold a reader’s attention, that is because it tends to resist answering these questions. But abstraction’s hold on Cusk isn’t quite complete, not yet, and she has one answer still to give: You got here because you were mothered. The book comes alive when Cusk turns to the mother-child relationship—a core preoccupation of hers—and transforms it into an all-encompassing theory of why identity hampers and hurts, a problem now of personhood itself as much as of the constraints that motherhood places on women. Every one of Parade’s scenarios features mothers, fleeing and being fled. Between mother and child is the inescapable agony of reciprocal creation. The mother weaves for her child a self; the child glues the mask of maternity onto the mother’s face. They cannot help wanting to run from what they’ve each made, despite the pain that flight exacts on the other. And so, pulling at and away from each other, mother and child learn the hardest truth: Every escape is bought at the expense of struggle and loss for both the self and someone else. Cusk is, as always, tough; she insists on the cost.

This is where Parade betrays some sign of turbulence beneath its detachment. The novel’s concluding section begins with the funeral of a mother, of whom we hear this, narrated in the collective “we” of her children: “The coffin was shocking, and this must always be the case, whether or not one disliked being confined to the facts as much as our mother had.” A knotty feeling emerges in this strand, sharp and funny—the angry rush of needs caught in the act of being denied, both the need for the mother and the need to be done with her. It is the closest Parade comes to an exposed nerve. We both want and loathe the specificity of our selfhood. Cusk understands the implicit, plaintive, and aggressive cry of the child: Describe me, tell me what I am, so I can later refuse it! That is the usual job of mothers, and also of novelists—to describe us and so encase us. By Cusk’s lights, we should learn to do without both; freedom awaits on the other side.

It may be, though, that the anguish of the mother-child bind feels more alive than the world that comes after selfhood. The problem is not that Cusk has trouble finding a language adequate to her theory of the burdens of identity—the problem may be instead that she has found that language, and it is clean indeed, scoured so free of attachments as to become translucent. Parade wants to replace the usual enticements of fiction—people and the story of their destinies—with the illumination of pure possibility. As such, the novel seems designed to provoke demands that it won’t satisfy. Be vivid! we might want to say to Cusk. Be angry; be savage; be funny; be real. Be a person. To which her response seems to be: Is that what you should want?

This article appears in the July/August 2024 print edition with the headline “A Novel Without Characters.”

What's Your Reaction?