QAnon for Wine Moms

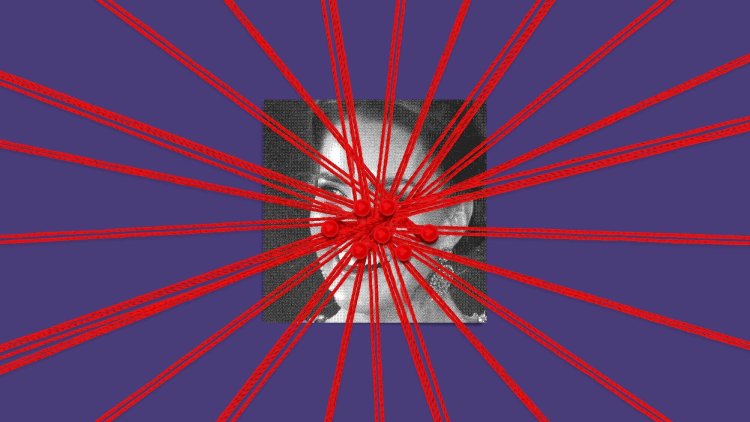

Kate Middleton needed privacy. The public had other ideas.

There was a time, not that long ago, when mainstream-news consumers pitied people who had succumbed to the sprawling conspiracies of QAnon. Imagine spending your days parsing “Q Drops,” poring over cryptic utterances for coded messages. Imagine taking every scrap of new information and weaving it into an existing narrative. Those poor, deluded, terminally online saps. What a terrible modern affliction.

And then some of my friends became Kate Middleton truthers.

In January, the British Royal Family announced that Catherine, Princess of Wales, had needed surgery for unspecified, noncancerous abdominal issues, and that her recovery would take longer than originally expected. She would therefore not resume public duties until after Easter. For several weeks, that explanation sufficed. But by late February, half the internet seemed to be speculating over her whereabouts, using the favored format of conspiracists everywhere: just asking questions. An absence is filled with puzzlement—what aren’t we being told?—and then larded with a garnish of suspicion. Why are they hiding the truth from us?

In the past few weeks, my WhatsApp groups have been taken over by friends wondering what is wrong with the Princess of Wales. American acquaintances, perhaps assuming that my Britishness gives me some mystical connection to the Windsors, have started texting me for updates. Everyone has a theory. Everyone wants to know.

[Read: Just asking questions about Kate Middleton]

But it’s more than that: Everyone also seems mystified by the simple fact of not knowing. We have become so used to smartphone surveillance, oversharing on social media, and the commercial harvesting of life events for content that the prospect of remaining uninformed about the state of a stranger’s intestines now seems like a personal affront. On March 4, a grainy photograph of Kate traveling in the passenger seat of a car with her mother, Carole, began to circulate, but it did not stop the speculation. Did her face look weird if you zoomed in to 20 times magnification? (Yes, but then so would anyone’s.) Where was Prince William? (Maybe with their kids?) Was the photo staged, as in Weekend at Bernie’s? (Come on.) Just to add fuel to the fire, that picture was not widely circulated in Britain. Again: What aren’t we being told? Why are they hiding the truth from us?

Over the weekend, the frenzy intensified when Kensington Palace released a photograph, supposedly taken by Prince William last week, of Catherine with her three children. Within hours, TikTok was full of momfluencers earnestly discussing the clumsy signs of editing on Prince Louis’s patterned sweater. Someone on X (formerly Twitter) put the photo in an online tool that deemed it AI-generated. Someone else claimed, in a post that went viral, that the photo had been taken in November, based on the family involved wearing the same clothes that they did on a trip to a food bank—edited to be different colors, for some reason. Another person jumped in to say that the shrub behind them was suspiciously green for early spring in England. And—oh, look—she didn’t appear to be wearing her wedding ring.

These assertions sounded plausible, and the sheer volume of them was self-reinforcing. But when I stopped to think, my brain somehow rewired itself. Why did I instantly believe in such a thing as an online tool that can precisely calculate the probability of a photograph being AI-generated? Why would Kensington Palace cunningly edit a white sweater to be navy—and then leave telltale signs of fakery, such as Princess Charlotte’s impossible sleeve? When I read a suggestion that Kate’s face had been lifted from her Vogue cover portrait, the spell broke. Maybe the faces looked the same … because they belonged to the same person?

Late on Sunday night, though, the photo agencies that had distributed the picture issued a “kill notice,” stating that the level of digital editing meant that it did not meet their standards. The Kate Middleton truthers gleefully concluded that their suspicions had been validated. Britain’s national newspapers, meanwhile, were furious: Most had splashed their front page with the image and now had to scramble to rewrite their coverage. One journalist who had written a column arguing that the photo had finally silenced all the “absurd speculation” updated it to observe that it had only raised more questions. Overzealous royal PR had taken a viral story and given it legitimacy.

The essence of conspiracism is that innocent explanations do not exist, and neither do unlikely coincidences. Participants reject Occam’s razor, the idea that the simplest explanation is usually correct. Which is more likely, that Catherine owns turtleneck sweaters in multiple colors, or that mysterious forces edited her white sweater to look navy to hoodwink onlookers? Conspiracists aren’t stupid, because photo editing does exist, and celebrities do sometimes remove their wedding ring in lieu of issuing a statement about a separation. But it’s revealing when the most lurid explanation is someone’s default setting.

Kate Middleton trutherism also feeds on the uncomfortable fact that mainstream media outlets don’t tell the public everything, and those gaps and omissions become highly visible in a world of global news brands and lightly regulated social media. British newspapers are members of the “royal rota,” a system that grants close access to the Windsors in exchange for pooling reports and photographs with other media outlets. In practice, the threat of exclusion from the rota also gives the royal PR team leverage to squash invasive or unwelcome stories. Prince Harry dropped out of it when he stepped back from being a working royal, and has since argued that it protected the core members of the family at his expense.

U.S. news outlets aren’t members of the royal rota, however, and American libel and privacy laws are much looser. That affects what they are prepared to publish. The result is that news consumers on both sides of the Atlantic can see that there are, in fact, things that the British papers aren’t telling or showing them. On March 4, when the first paparazzi pictures of Catherine were taken, British royal correspondents said that Kensington Palace had pressured them not to use the photographs because of privacy concerns. They complied, but the New York Post had no such qualms. And even American tabloids have limits on what they will publish, whereas social-media platforms spread rampant speculation about the couple’s marriage that neither British nor American newspapers will touch. The average X or TikTok user is not afraid of losing their place on the royal rota, nor of being sued.

[Read: Kate Middleton and the end of shared reality]

The current controversy demonstrates another tension between the royals and the press. News agencies have been unhappy for some time about politicians and royals supplying “handout” images instead of inviting journalists to take their own. British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has an official photographer whose pictures, unsurprisingly, tend to make him look statesmanlike rather than silly. These are supplied to newspapers on days when no news images of Sunak are available, so they end up being widely used. Similarly, Kate Middleton is an enthusiastic amateur photographer who has taken many of her children’s birthday portraits herself. By acting like this, Sunak and the princess have deprived working journalists of professional opportunities—and editorial independence. For that reason, withdrawing the digitally altered royal photo probably wasn’t a hard decision for photo agencies. They wanted to make a point.

They also made the right call by doing so. In the era of deepfakes, transparency about where images come from and how they are created is more important than ever. Journalists have realized that much less is taken on trust these days: After the photo was withdrawn, an analysis of its metadata showed it was taken at Windsor, where the couple live, and edited twice in Adobe Photoshop. Catherine herself took the blame for the image, writing in a statement that “like many amateur photographers, I do occasionally experiment with editing.”

Did this help? Of course not. All of five minutes passed before I saw someone just asking a new question: How did she have the time and energy to do all this photo editing while recovering from an operation?

Two other factors have made this story so potent. The first is that visibility is a royal necessity: As the late Queen once said, she had to be seen to be believed. Monarchy, like the American presidency, also reduces power to a human scale, and so the state of Catherine’s health is interesting for the same reason voters fret about Joe Biden’s age. Both figures sit inside constitutional frameworks that limit their actions, and both (to be brutally honest) are replaceable. Yet the public fairly wants to know that Biden is in charge, not Kamala Harris or the White House chief of staff or Barack Obama from a secret Kalorama lair. In the same way, members of royal families become blank canvases, allowing the rest of us to project our cultural anxieties onto them. The resulting characters are both very grand and very relatable: the wayward son, the embarrassing uncle, the scorned wife. They are also famous for being famous, and so their private lives are not their own.

Connoisseurs of monarchy will recall a recent precedent for the Kate situation. In 2021, Princess Charlene of Monaco—married to Albert, an ex-playboy two decades her senior with two children from casual relationships—suddenly left the principality, and her young twins, to spend 10 months in South Africa, where she grew up. The explanation for her absence started out as a “conservation trip,” then became recuperation for an ear, nose, and throat operation. When she returned to Europe, she checked into a Swiss clinic for “exhaustion.” The headlines about Charlene’s condition were every bit as relentless as those surrounding Kate, but with a far smaller reach. The Monegasque royals have glamor—Albert is the son of the Hollywood star Grace Kelly—but they also rule over a territory about the size of an Applebee’s parking lot. By contrast, the Windsors are a global brand.

The second reason for the virality of Kate Middleton trutherism is that it is a classic Easter-egg hunt. Or if you prefer a more modern reference, it’s an MMORPG—a massive multiplayer online role-playing game. Communities form around clues and symbols, discrepancies in the prevailing narrative are identified, dossiers are collated, and public statements are scoured for alleged omissions. And the atmosphere, as my colleague Charlie Warzel has written, is one of self-aware irony. Aren’t we crazy to care about this so much? The underlying sense that none of this really matters enhances the sensation of playing a game.

The first interactive news event like this that I can remember was the hunt for the Boston Marathon bombers in 2013. After the two men responsible went on the run, what followed was called “the most crowdsourced terror investigation in American history.” Everyone pretended to be doing vital national-security work, but really they were playing a massive online version of Clue.

Amid all this amateur police work, however, one of the largest Reddit forums dedicated to the manhunt identified a student named Sunil Tripathi as a suspect. Users began to harass his family, before it became clear that he had gone missing a month before the bombing. (His body was later found in a local river.) At the time, Reddit General Manager Erik Martin apologized for adding to the burden of a worried family. “Though started with noble intentions, some of the activity on reddit fueled online witch hunts and dangerous speculation which spiraled into very negative consequences for innocent parties,” he wrote. “The reddit staff and the millions of people on reddit around the world deeply regret that this happened.”

Internet users didn’t regret it that deeply, as it turns out, because many similar events have occurred over the past 11 years. My social-media feeds are regularly full of suggestions that, say, Biden has body doubles, and here are the 19 angled lines drawn on his face that prove it. Taylor Swift has become a master of dropping clues through clothes, color schemes, and coded lyrics. Or think of the thousands of hours of TikTok videos dedicated to Johnny Depp’s libel action against Amber Heard: her facial expressions in court were replayed and picked apart, along with every detail of their marital arguments. When a story becomes big enough, every outlet has to write about it—either to harvest the eyeballs (and ad revenue) on offer, or just to prove that they, too, know it exists.

Does this matter? Well, if you’re the Princess of Wales or her family, it does. A request for privacy has morphed into a giant online game designed to invade it. But the story is also remarkable for the insight it gives us into the challenges facing traditional media. Trust is low, gatekeeping is impossible, and even people who probably once deplored tabloid intrusion into royal affairs and eating disorders are now firing up TikTok and getting sucked into a nine-part video series about the opacity of Princess Charlotte’s sleeve. This is QAnon for wine moms. And the dynamics behind it are not going away.

What's Your Reaction?