Now Is the Time to Wrestle With Frantz Fanon

Does the patron saint of political violence have anything to teach us today?

Some ideas exist so far beyond one’s own moral boundaries that to hear them articulated out loud, unabashedly, is to experience something akin to awe. That’s how I felt, anyway, when I watched the video of a Cornell professor speaking at a rally a week after Hamas’s October 7 attack. “It was exhilarating!” he shouted. “It was energizing!” The mass murder and rape and kidnapping of Israelis on that day had already been well documented. I saw an atrocity; he saw renewal and life. Gazans, he exclaimed, “were able to breathe for the first time in years.”

The professor spat out these words, but I heard another voice too. It belonged to Frantz Fanon.

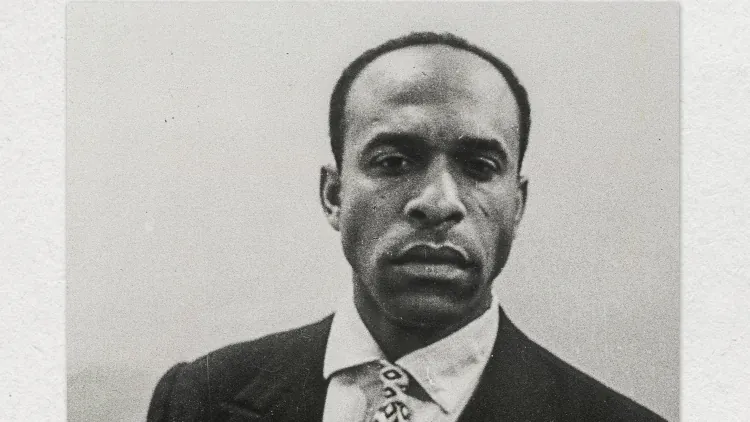

The mid-century theorist of decolonization has long been the patron saint of political violence. Since his death in 1961, at the age of 36, Fanon’s concepts have provided intellectual ballast and moral justification for actions that most people would simply describe as terror. For him, the world divided neatly into two groups, the colonized and the colonizer. Innocent civilians didn’t figure much into this dichotomy. When posters bearing photos of Israeli toddlers abducted to Gaza were vandalized and the word kidnapped replaced with occupier, that was pure Fanon. His argument, articulated in “On Violence,” the provocative first chapter of his book The Wretched of the Earth, has the efficiency of a syllogism, as seemingly self-evident as an eye for an eye: The violence of colonialism has robbed the colonized of their humanity; to regain a sense of self, they must commit the same violence against the colonizer. “For the native,” Fanon wrote at his bluntest, “life can only spring up again out of the rotting corpse of the settler.”

Was there more to Fanon? Even a child understands that violence begets only more violence, that a slap to the face creates the conditions for a return slap, or a fist, or a bullet. And what had Hamas’s “exhilarating” invasion into Israel produced for Palestinians, besides ruin, unbearable suffering, and mass death? In a new biography, The Rebel’s Clinic, Adam Shatz, an editor at the London Review of Books, aims to rescue Fanon from reduction. Shatz openly admires the Martinican psychiatrist turned Algerian revolutionary. He respects his élan and his spirit of resistance. And he sees lasting value in Fanon’s theories about the toll racism and colonialism take on the body and brain—insights that have proved extraordinarily generative, sprouting thousands of academic monographs over the decades. As for the advocacy of violence, Shatz does not excuse it; he even calls it “alarming” at one point, though that’s about as far as he goes. But like Fanon’s longtime secretary, Marie-Jeanne Manuellan, who laments to Shatz that her boss has been “chopped into little pieces,” the biographer wants to put this most provocative piece of Fanon into its proper context—to borrow a newly loaded word.

Shatz is not the first to take the full measure of Fanon, and he draws much from a definitive 2000 biography by David Macey and a handful of memoirs from those who knew the man. The uniqueness of this new book is rather in the ways it connects the intellectual dots of Fanon’s life—Aimé Césaire to Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir to Richard Wright to the many theorists, such as Edward Said, who found in Fanon an inspiration. Understanding Fanon as a “prophet,” Shatz writes, “treats him as a man of answers, rather than questions, locked in a project of being, rather than becoming.” The becoming is what matters to Shatz, the associations and influences, the alienations Fanon felt, and the epiphanies that emerged from them.

Fanon did call violence a “cleansing force,” but Shatz believes that the idea was rendered cartoonish almost from its first utterance—and by no less than Sartre in an infamous preface he wrote for the The Wretched of the Earth. By trying to out-Fanon Fanon, Sartre hyped the notion of decolonization as a zero-sum game, one in which Europeans would have to die for the colonized world to be born; this was, Shatz writes, a “parody” of Fanon.

So how did Fanon see violence? Armed resistance was a necessity for oppressed people—a perspective easy to agree with, especially when the oppression seems to foreclose any other option. But for Fanon, violence was not just about necessity; it was also positive in and of itself, serving a psychological end. Much like the electroshocks Fanon prescribed his patients, violence rebooted the consciousness of a colonized person by releasing him from his “inferiority complex and his passive or despairing attitude.” This was not military strategy. This was therapy. And in its name, Fanon tacitly condoned a lot of killing, and not just of people in uniform. When the revolutionaries he had joined placed bombs in cafés where they murdered women and maimed children, he didn’t walk away. The oppressed needed violence in order to be made whole. Colonialism and its underlying racism had physical effects on its subjects. (A new book, Matthew Beaumont’s How We Walk, uses Fanon to look at how this oppression affects a person’s actual gait.) Achieving full humanity was possible only through an equivalently embodied act of overwhelming one’s oppressor.

The point of violence, then, was not to “cleanse” in any kind of outward sense. In fact, Shatz thinks this word—which does have a whiff of ethnic cleansing—is a mistranslation. The original French is “la violence désintoxique,” and Shatz prefers the clumsy but possibly more accurate “dis-intoxicating,” an inwardly focused act—to sober oneself up, to wake the colonized from, Shatz writes, “the stupor induced by colonial subjugation.” It’s a subtle shift, one example of Shatz trying to usher in a more complex and possibly palatable version of Fanon. And I guess “dis-intoxicating” does seem less gratuitous a reason for killing than “cleansing,” though I’m not sure the distinction would matter much to a child blown up in a café.

I should add that Fanon didn’t always write about this psychological dimension of killing with praise or gusto. In Shatz’s more expansive view, we see Fanon slip back and forth from militant advocacy to a kind of scientific-observer status, making it hard to know sometimes where he stood in relation to the violence he was theorizing about. Often Fanon appears simply to have been sketching out the mechanics of decolonization, and arriving at conclusions that make for very poor slogans: “The colonized subject is a persecuted person who constantly dreams of becoming the persecutor.”

Not just the depth of his thinking but also Fanon’s ultimate idealism has been lost, Shatz insists. Despite the lurid visions of death, Fanon was an optimist who hoped that the necessary physical confrontation between colonized and colonizer would produce a “new man” and a fresh world of egalitarianism and individual freedom. Though he has been championed by movements of Black identity in his afterlife, Fanon himself did not draw his sense of self from a connection to his ancestors or the reclamation of an African past (he rejected, in fact, the Negritude movement, which sought to do just this). He didn’t believe that race could be ignored, but he emphatically did not want to be defined by it. He wanted race to be overcome. He looked instead to the future, to a postcolonial utopia that would level all the old power structures. “Superiority? Inferiority? Why not the quite simple attempt to touch the other, to feel the other, to explain the other to myself?” he wrote. And in this future of inclusivity and justice, the lion would finally lie down with the lamb.

How exactly this transformation would—or could—take place, given the many corpses Fanon imagined would litter the path there, Shatz has to admit, “Fanon did not explain.”

This disconnect is jarring. And Shatz doesn’t try to resolve it; he knows he can’t. He calls his reading of Fanon “symptomatic,” attuned to “gaps, silences, tensions, and contradictions”—of which there are many. Fanon died young and didn’t have time for memoir; little remains that might offer insight into his inner life. He comes across here as intellectually and physically restless. Even his books were acts of “spoken-word,” as Shatz describes them, dictated while pacing and letting his thoughts fly. But we do have the facts of Fanon’s life—the actual revolution to which he wedded himself—and the evolution of his thinking, which Shatz engagingly and efficiently lays out. And these provide the most convincing counterargument to the sort of killing that Fanon validated. The pieced-together Fanon who emerges from Shatz’s study is a man who should have known better. His own actions, his own writing, provide enough evidence of just how self-defeating and self-immolating violence can be.

The first words that the future mortal adversary of colonialism learned to write were “Je suis francais”—“I am French.” Fanon would eventually throw in his lot with the powerless, but he was born in 1925 into a middle-class family on the Caribbean island of Martinique, a French colony since the early 17th century. His parents were part of an aspiring class: devoted subjects of the metropole who had worked hard to assimilate and leave behind the island’s history of slavery, certainly not eager to rebel. Shatz suggests that while growing up, Fanon didn’t ever identify as Black. He saw himself instead as a French West Indian.

This relationship to France and his own racial identity underwent a radical change during and after World War II. Fanon eagerly enlisted and found himself fighting in Europe, even sustaining a shrapnel injury in the fall of 1944 during a battle near France’s eastern border. It was in this experience of war, alongside both white soldiers and those from the African colonies, that he first understood how he was seen by his fellow Frenchmen, that his skin made him a second-class citizen to them. This shocked him—he was “wounded to the core of his being,” his brother Joby would later write. The slights added up. He never forgot, for example, the white Frenchwomen who refused to dance with him after the news of liberation, choosing American soldiers instead (and Fanon, Shatz reveals in one of the book’s rare personal details, secretly loved to dance).

One particular incident became an origin story of sorts, recounted in Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon’s first book, published in 1952. Once the war was over, he remained in France and attended medical school in Lyon, a city with few Black people where he was continuously reminded of his difference. One day while riding the train, a little boy fearfully pointed at him and said to his mother, “Look, maman, a nègre!” Fanon tried to smile, to diffuse the awkwardness, but he felt rage well up inside him. When the mother tried to calm the scared boy by saying, “Look how handsome the nègre is,” Fanon couldn’t hold back any longer. “The handsome nègre says, fuck you, madame,” he burst out. The rupture with social norms felt freeing. “I was identifying my enemies and I was creating a scandal,” Fanon wrote about the moment. “Overjoyed. We could now have some fun.”

Fanon understood himself to be the other, and knew that he would never escape the limitations this imposed on him. “Whatever he did—take a stroll, dissect a corpse, make love, speak French—he did while being Black,” Shatz writes. “It felt like a curse, or a time bomb in his head.” The only way to overcome the feeling of being pinned down was to squirm, as he had done on the train—to refuse it. Existentialism, for this reason, served as a helpful philosophy for Fanon when he discovered and embraced it in the late 1940s. Sartre was concerned with the problem of human freedom and the ways we are being constantly hindered by the “gaze” of another, defining and thereby constraining us. His 1946 book Réflexions sur la Question Juive became a source text for Fanon: It explained how anti-Semites’ fears had effectively “created” the Jew, much as the psychological projections of the white world around him made Fanon Black in ways he detested and wanted to push back against.

Biographers, including Shatz, have not been able to pinpoint exactly when during his medical studies, or why, Fanon drifted toward psychiatry. But the field would give him a chance to explore how these societal oppressions—which he began to think of as a kind of atmospheric violence—shaped the individual. Black Skin, White Masks, his first book, grew out of his original, but rejected, idea for a doctoral thesis. By the late 1940s, when he started composing it, he had concluded that to become fully human—that is, free from being seen in the way that he believed Black men were, as simply an “oppositional brute force” to Western civilization—one had only a single option: to try to become white. But this, of course, was impossible, a Sisyphean task. A mask of whiteness can be attempted, but it will always be just a mask, and the effort to keep it on is its own kind of torture. “Another situation is possible,” Fanon declared, but “it implies a restructuring of the world.”

Only revolution could bring about this restructuring. But Fanon could not have known, when he arrived in the agitated French colony of Algeria in 1953, that he was about to find himself, almost by chance, in the middle of one. At the age of 28, he was sent by the French government to be the director of a psychiatric hospital in a small garrison town called Blida, and he eventually began noticing all the ways colonialism itself was the main cause of his many patients’ mental illnesses. But he also saw in the Algerians’ refusal to assimilate, to wear the mask, a powerful force to which he wanted to attach himself. “They persisted in saying no to the French,” Shatz writes. “To their medicine, to their lifestyle, to their food, to their judicial system—to the amputation of their identity that colonialism sought to inflict.”

When an uprising against France began at the end of 1954, Fanon quietly but subversively used his hospital to help treat fighters with the National Liberation Front, known as the FLN. A rebel assault launched in the harbor city of Philippeville in August of 1955 was a pivotal moment for him and the country—“the point of no return,” as Fanon would later put it. Coordinated by the FLN, groups of peasant militias attacked civilians, mostly European, with pitchforks, knives, and axes, massacring dozens in the streets and in their homes. The French were horrified and retaliated ruthlessly, shooting hundreds of Algerian men without trial. The episode brought out into the open and made explicit for Fanon both the violence of colonialism and the necessary counterviolence of decolonization. Fanon tied his fate to the FLN and was expelled from Algeria in early 1957, becoming part of the resistance in exile in neighboring Tunisia. Until his death only four years later, he devoted himself entirely to the cause.

In joining the FLN, Fanon had to toss into the fires of the revolution many of his own intellectual and moral commitments. He had believed in individuality, in the pursuit of a restructured world liberated from the violence that had so psychically corroded the minds of his patients. But now he was a soldier, subordinate to a militant movement whose methods and aims would seem to diverge wildly from Fanon’s ideals. Shatz doesn’t ignore this tension, but he also stops short of reckoning with the jumbled and irreconcilable set of principles Fanon would try to maintain. He falls back instead on his basic appreciation for Fanon’s energy and full-bodied dedication. Shatz thinks that “for all that he tried to be a hard man, Fanon remained a dreamer.” But his biography shows the opposite: The dreamer may have dreamed of a common humanity, but to get there, he jumped in a car with hard men and became one himself.

The Algerian Revolution, like most revolutions, ate its own. Among the victims was Abane Ramdane, a prominent FLN leader who had respected and vouched for Fanon, sharing his vision of a modern, inclusive, secular Algeria. In 1957, leaders more interested in, as Shatz puts it, “the restoration of Muslim Algeria, not social revolution” gained the upper hand in an internal FLN power struggle. On their orders, Ramdane was strangled to death by the side of a road. Fanon knew of the murder. But whether out of allegiance to the movement or fear for his own life—according to another FLN leader, Fanon was on a list of men to be executed in case of internal revolt—he said nothing.

Fanon had to lie, regularly. One of his roles while based in Tunis was to edit a newspaper, the FLN’s mouthpiece, El Moudjahid. As an editor, his attitude toward the truth followed the same binary logic as his ideas about violence: What they do to us, we can do to them. “In answer to the lie of the colonial situation, the colonized subject responds with a lie,” he wrote in The Wretched of the Earth. “In the colonial context there is no truthful behavior. And good is quite simply what hurts them most.” When the FLN rounded up and killed more than 300 men outside the village of Melouza for supporting a rival rebel group, Fanon denied publicly that it had happened, though he knew otherwise. Writing about it later, he offered the weak defense that the French had done worse.

This pattern, of looking to the colonizer to justify the actions of the colonized, shows up consistently in these revolutionary years, as if Fanon, despite being once convinced by existentialism of his own boundless freedom, is trapped in a mirror. “The very same people who had it constantly drummed into them that the only language they understood was that of force, now decide to express themselves with force,” Fanon wrote. “To the expression: ‘All natives are the same,’ the colonized reply: ‘All colonists are the same.’” When Fanon began making connections among the independence movements of sub-Saharan Africa, he imagined a united force to help the Algerians, one that could “hurl a continent against the last ramparts of colonial power.” As Shatz notes, this was “anti-imperialist rhetoric” that “had the ring of colonial conquest.”

The more he threw himself into the Algerian fight, the more blind Fanon seems to have become to what that cause actually represented. The desire to bring back a traditional Muslim way of life from before the French arrived—with the implications this held for the role of women or nonbelievers—became the animating force of the uprising and the essential purpose of throwing off colonialism. Whereas for Fanon, as Shatz puts it, the struggle was always about battling “class oppression, religious traditionalism, even patriarchy,” such values were nowhere near the top of the FLN leadership’s own goals by the early 1960s. Indeed, if he had lived to see a free Algeria, it’s doubtful that Fanon—who didn’t even speak Arabic—would have found a place for himself in the brutally autocratic country that emerged.

Did Fanon know what he was giving up when he joined the Algerian Revolution? Shatz sees the moral compromises as “a tactical surrender of freedom that did not escape his notice or leave him without regrets.” Yet this seems to be a projection on Shatz’s part; at any rate, he unearths little evidence of those regrets in Fanon’s own writing.

By the time he finished dictating The Wretched of the Earth, in 1961, Fanon was sick with the cancer that would kill him. That final book was a desperate last will and testament, and one that appears in retrospect to capture the “striking ambivalence,” as Shatz puts it, of Fanon’s worldview. It opens with the “militant self-certainty” of “On Violence.” And it ends with a series of case studies from Fanon’s psychiatric practice in Algeria, which depict just how debilitating and long-lasting the effects of living in a society marked by violence can be. He offers the story of a man who witnessed a massacre in his village and developed a desire to kill as a result, and describes a European police officer who brings home the brutality he has to inflict every day, torturing his wife and children.

For the oppressed, violence can feel like the only way out of a life that is otherwise encased by walls, like the only means of survival. And Fanon does understand, better than any other thinker, the vertiginous high of standing over your tormentor, of regaining a sense of agency. His solution feels like an unambiguous, cosmically just response to the day-to-day violence of colonialism, and it’s not hard to understand why it might feel like the only way toward freedom. After enough death, France did, in the end, leave Algeria. But if violence is also meant to be ennobling, this aspect of it is, as Shatz describes, “ephemeral at best.” What lasts longer—and Fanon the psychiatrist is keenly alert to this—is how permanently damaging violence is to whoever perpetrates it. Fanon's surreal denial of this knowledge, his belief that somehow slicing the throat of the colonizer will lead to a new, more equitable reality and not just more violence, is hard to comprehend.

The best case Shatz makes for not being repelled outright by Fanon’s bloody vision is his suggestion that The Wretched of the Earth be read “as literature”—in fact, this might be the key to understanding his continued appeal for readers, a narratively satisfying way of resolving the world’s wrongs with the slash of a sword. Fanon had a literary sensibility, and possibly, Shatz writes, it may have carried him into starker territory than he fully intended, producing an allegorical text that resembled something out of Samuel Beckett’s mind—with the colonized and colonizer as “archetypes locked together in fatal contradiction.” “On Violence” does contain some strikingly poetic passages. Fanon wrote, for example, about how the physical oppression of colonialism expresses itself in dreams:

The dreams of the native are muscular dreams, dreams of action, aggressive dreams. I dream that I am jumping, that I am swimming, that I am running, that I am climbing. I dream that I’m bursting out laughing, that I’m crossing the river in a single stride, that I’m being pursued by a pack of cars that will never catch me. During colonization, the colonized never ceases to liberate himself between the hours of nine in the evening and six in the morning.

Fanon evokes powerlessness and the anguish of trying to regain control of one’s own life. This makes The Wretched of the Earth “rich in dramatic potential,” as Shatz writes. If only Fanon’s book was meant to be read as a novel or as poetry—but it wasn’t. It was intended and understood as a prescription.

Violence felt inevitable to Fanon, but he lived in a moment when other possibilities existed. Gandhi’s Salt March took place within his lifetime, as did the Montgomery bus boycott. These movements, with stakes just as high as those of Algerian independence, self-consciously countered the brutality of the oppressor with humanistic tactics. Change came not from mimicking violent behavior but from deliberately, and with great discipline, avoiding it, breaking what Martin Luther King Jr. called “the chain reaction of evil.” Nonviolence had, of course, its own dangers and detractors—Fanon would probably agree with Malcolm X, who looked at children being attacked with fire hoses and police dogs in Birmingham in 1963 and said, “Real men don’t put their children on the firing line.” But the approach of the civil-rights movement in these years achieved concrete victories against discrimination before it devolved into its own forms of militancy. In Africa, the majority of countries that became independent while hundreds of thousands were dying in Algeria did so through peaceful if tense negotiations with the colonial powers. Moreover, during Fanon’s life, the world had already seen what happens when violence is thought of as a “cleansing force.” Even the language Fanon used was somewhat familiar. “Only war knows how to rejuvenate, accelerate and sharpen human intelligence for the better,” wrote Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the leader of the Italian futurists (and an eventual fascist) in the first months of the bloodbath that was World War I.

And if armed conflict seemed the only way for Algerians to shake off France’s long domination, Fanon could have remained more intellectually honest, and less tangled in contradiction, by taking a critical stance. Others did just this. Albert Memmi was a Tunisian Jewish intellectual who, like Fanon, saw the harm caused by colonialism and racism to be “as unbearable as hunger.” But he understood that the militants fighting French rule were using means that represented a choice “not between good and evil, but between evil and uneasiness.” He supported armed resistance with open eyes about the consequences of all this killing and an awareness that the type of society the revolutionaries were fighting for would ultimately be inhospitable to him and his own marginalized identity as a Jew.

The Fanon of “On Violence” hardly blinks; no room for “uneasiness.” And this makes it nearly impossible for Shatz to grant the nuance he so desperately wants to accord Fanon. Alongside the intellectual drama, there is also a Freudian psychodrama that weaves its way through the biography, and it comes closest to explaining Fanon’s motives: a disgruntled son who came to detest what he saw as the passivity of his native Martinique, a land of formerly enslaved people whose freedom was granted to them by their colonizer; a man who chose France as his adopted father, but then decided to kill his connection to this father country when it betrayed him by making him feel he wasn’t a true son. When Fanon took up the Algerian cause, it was with the “zeal of a convert,” writes Shatz. An Algerian activist and historian, Mohammed Harbi, who knew Fanon, said he had “a very strong need to belong”; this is a quality that could easily drive someone to excesses of unquestioning loyalty. He wanted a home.

This more psychological portrait does help us better understand why Fanon didn’t seem to see his own deep contradictions, or why he couldn’t extricate himself if he did. But it also undermines Shatz’s project to bring together all the pieces of Fanon, to rescue him from “vulgar Fanonism,” to present him as a more complex, textured thinker. His pervasive rage is particularly damaging, so Shatz largely ignores it—for example, he does note Fanon saying he had to be a “god” to his wife, Josie, but doesn’t engage with recent research that alleges he hit her in front of others, or the many moments in Fanon’s writing where darkness bubbles up (“Just as there are faces that ask to be slapped, can one not speak of women who ask to be raped?”). Perhaps to really understand Fanon is to return to that moment on the train in Lyon when the little white boy looked at him in terror and he responded with the anger of a man who just couldn’t bear any longer to live in society as it was. “I exploded,” Fanon wrote about that moment and its aftermath. “Here are the broken fragments put together by another me.”

The fragments are razor-sharp, even as they glisten. They are worth picking up carefully and scrutinizing. But at a moment when we are badly in need of new ways of seeing one another, of recognizing humanity in one another, I’m not sure how helpful those fragments are, because they will cut you. And you will bleed and bleed.

What's Your Reaction?