My Favorite Trails Are Destroyed

Easy access to nature is what makes my hometown special. Now some of its signature hikes are burning.

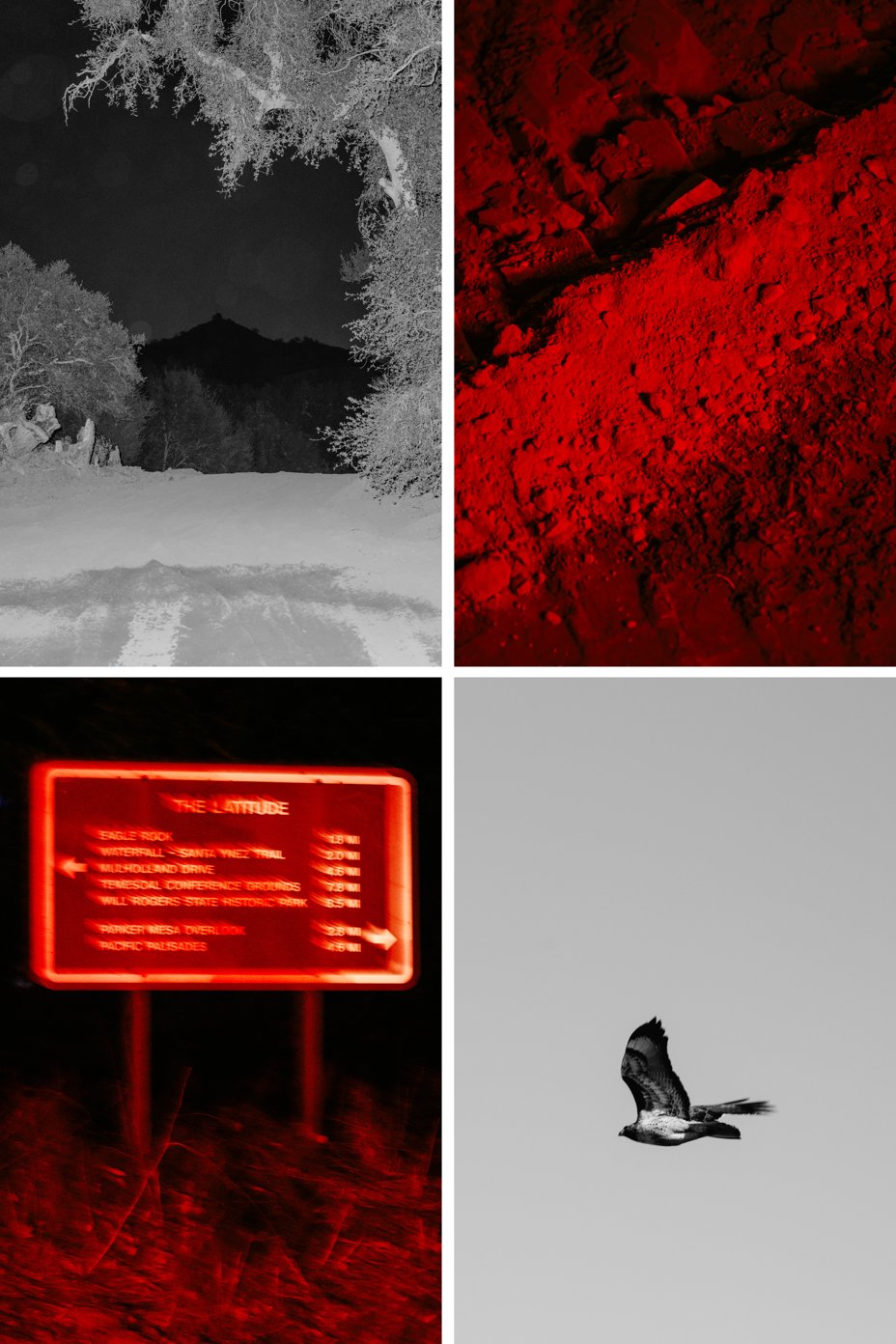

Photographs by Daniel Dorsa

One of the worst-kept secrets in Los Angeles is a 130-acre swath of chaparral. On perfect weekend afternoons, I have walked my dog among the crowds at Runyon Canyon Park, a piece of rolling scrub nestled in the Hollywood Hills. I’d go more often if finding parking on Mulholland Drive wasn’t nearly impossible. In a city that loves the outdoors, Runyon is the premier Sunday-afternoon trail: a dusty-chic destination for after-brunch hikers, families, couples on first dates, and everyone else from around the city to get in steps, spot movie stars, or both. What makes the area so popular is that it’s a mountain hike in the middle of the city—across the freeway from Universal Studios and over the hill from the Hollywood Bowl. Rugged paths lead downhill to meet Hollywood Boulevard, close to the Walk of Fame.

As colossal wildfires have raged across L.A.—the most destructive in the city’s history—Runyon Canyon has not been spared. Last week, a blaze erupted in the heart of the park, forcing some nearby Hollywood residents to flee. Mercifully, firefighters halted the march of the flames before they turned into another major fire. But the blaze still left a 43-acre scar across the expanse. Treasured trails are charred.

Compared with all that has been lost here in L.A., the devastation of Runyon Canyon and other hiking trails is trivial. Colleagues of mine have lost their homes. Entire neighborhoods have been wiped out, and winds threaten to keep fanning the flames. At least 25 people have died. Against the grim scale of this disaster, those ruined trails are a quieter kind of loss that the city will have to reckon with. Core to L.A.’s identity is easy access to nature—wild trails and canyons and vistas—along with perfect weather for visiting them almost any day of the year. Even the Hollywood sign is at the end of a hike. Just like that, many of the signature places to get outdoors have been wiped out.

The city burns because the city is wild. Multiple mountain ranges that demarcate the disparate communities of Los Angeles County create picturesque settings for homes—in dangerous proximity to scrub that is prone to catching fire. Those same areas house an ample supply of easily accessible trailheads that make these peaks and canyons our backyard. On the trails, dadcore REI hikers like me intermingle with athleisure-clad Angelenos who look like they started walking uphill from an Erewhon and wandered into mountain-lion territory. We cross paths with flocks of students carrying Bluetooth speakers, 5 a.m. trail runners, and tourists who underestimated the ascent to Griffith Observatory.

Any given morning in the secluded heights of Pacific Palisades, you would have found hikers on the hunt for a precious legal parking spot between the driveways. From there, well-worn paths lead through Temescal and Topanga Canyons, up to lookout points where hikers could watch the city meet the sea. It now appears this beloved area is destroyed. The horrific Palisades Fire may have started at a spot near the popular Temescal Ridge trail. Despite heroic, lifesaving firefighting, the fire continues to burn deeper into Topanga State Park. Gorgeous hiking country above Pacific Palisades may be closed off to the public for years as the area recovers.

The Eaton Fire, the other major blaze, has also claimed some of the most beautiful spots around L.A. The fire’s namesake, Eaton Canyon, is home to a waterfall so photogenic that you once had to make a reservation to hike its trail. The blaze has burned up that walk, along with so many more in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains: trails that take you to Echo Mountain, Millard Falls, or toward the historic Mount Wilson Observatory that overlooks the city.

These bits of the outdoors have defined my life here, as they have for so many others. Those San Gabriel hikes are where my wife and I spent much of our time during the pandemic. The month after we got our dog, Watson, in 2020, the world shut down. There was nothing to do but hike. We drove to the trailheads that dot the Angeles Crest Highway, where hikers’ dirty Subarus dodge the gearheads who test their modified racers on the mountain curves. We parked in now-devastated parts of Altadena to get lost in the stunning foothills. We walked among the yucca all spring until Southern California’s unrelenting summer sun forced us indoors.

Much of L.A.’s nature still remains intact, of course. But even before the current fires, the sprawling Angeles National Forest that houses those peaks and trails of the San Gabriel Mountains has had it tough. In the autumn of 2020, the Bobcat Fire burned all the way across the range from north to south, torching 100,000-plus acres. This past fall, the Bridge Fire burned new patches of the mountains, with flames creeping toward the mountain town of Wrightwood and the ski slopes. Some of the areas my wife and I would traverse during the pandemic were decimated during these previous fires, and they are still recovering.

Los Angeles County was ready to burn. The wet winters of the past two years helped keep the big blazes at bay. The current mix of drought and ferocious winds have proved to be prime conditions for a major fire. These conditions will inevitably return, and they will bring more flames that scorch L.A.’s trails. Yet the growing incidence of wildfire, and its threat to our most loved natural spaces, is far more than a California story. Forest fires are getting worse all around the globe; nearly a third of Americans live somewhere threatened by wildfire. National parks, forests, and other irreplaceable places for communing with nature are under threat. Last month, a 500-acre fire sparked by a downed power line burned up a big chunk of a national forest in North Carolina. In November, a brush fire broke out in Brooklyn’s Prospect Park.

Here in L.A., the city has only started to contend with the toll of these wildfires. On top of the lives, homes, and businesses, the legacy of the destruction will include natural areas. Los Angeles is hiking to Skull Rock just as much as it’s rolling down Imperial Highway. It is the studio lot and the Santa Monica Mountains. The open spaces all around us invite Angelenos to ditch the concrete grid for the wandering switchbacks. With so many trails that are damaged and closed, the mountains aren’t calling quite as loudly as they used to.

What's Your Reaction?