Miranda’s Last Gift

When our daughter died suddenly, she left us with grief, memories—and Ringo.

I was at the kitchen counter making coffee when my daughter Miranda’s dog approached. Ringo stands about 10 inches high at the shoulder, but he carries himself with supreme confidence. He fixed his lustrous black eyes on mine. Staring straight at me, he lifted his leg and urinated on the oven door.

After the mess was cleaned up, I complained to Miranda, “I don’t think Ringo likes me.”

Miranda replied, “Ringo loves you. He just doesn’t respect you.”

Theoretically, Ringo is a Cavalier King Charles spaniel. You may have seen depictions of the breed peeking at you from portraits of monarchs and aristocrats. But the spaniels in the paintings are almost always the cinnamon-and-white variety known as a Blenheim spaniel. My wife, Danielle, has a Blenheim. The Blenheim Cavalier is a true lapdog: easygoing, obedient, insinuating. Ringo is very different. He is exactly the color of a cup of espresso, mostly black-haired with a little brownish tinge at his extremities. He’s commonly mistaken for a miniature Rottweiler. That confusion is less absurd than it sounds. If an unwelcome stranger steps in his way, 18-pound Ringo will stiffen and growl, murder in his eyes.

Ringo came into my life in the spring of 2018. Miranda had returned to the United States after four years living in Israel. She had thought seriously about staying there, but then the romantic relationship that had kept her in the country ended. Miranda was cast alone upon the open world. She relocated to Los Angeles to start over.

She chose L.A. because the landscape reminded her of Israel, even if the people were as different as could be. “My Israeli friends criticize Los Angeles as so fake,” she told me. “But let me tell you, fake nice is a lot better than authentic rude.”

Los Angeles, however, is not a good place to recover from a broken heart. The huge distances that must be traveled to see a friend, the cultural obsession with the surface of things—they can reinforce loneliness. Normally so cheerful and optimistic, Miranda was slowly succumbing to depression. So Danielle and I bought her a dog.

The dog we meant to buy was a Blenheim. Miranda had grown up with one and dearly loved him. But the breeder Miranda selected had no Blenheims for sale, only a single black-and-tan male. Miranda brought him home.

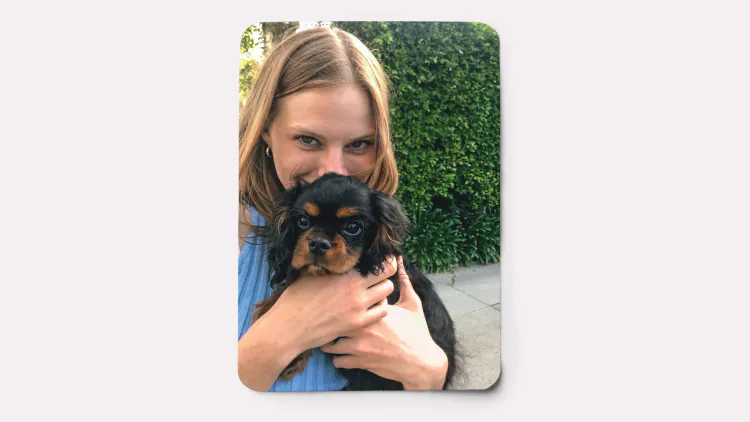

The friend who drove Miranda and Ringo back to L.A. took some photographs of the two of them in the car. Miranda—this glamorous and sophisticated young woman, who had earned her living as a model in Tokyo, Milan, and Tel Aviv—suddenly looked like her 11-year-old self again. She and Ringo writhed together in mutual delight, Miranda smiling in perfect happiness.

“Ringo is the best gift you and Mom ever gave me,” she said, “including the gift of life.”

I happened to visit Los Angeles a few days later, so I was the first member of the family apart from Miranda to meet Ringo. He worried me. I had imagined a dog that would curl up in Miranda’s lap when she needed an understanding companion, who would gently lick the tip of her nose if she was sad. This dog was a lot—what’s the word?—livelier than that. He was ferociously energetic, utterly inexhaustible. Oh well, I thought, he’s still just a puppy.

Ringo’s energy proved good for Miranda. If there was to be any living with him, he needed a long hike every day, preferably much of it uphill. His infectious spirit got him into situations where Miranda rapidly made new friends. They adapted each to the other. They did almost everything together. Men who sought Miranda’s favor learned to bring treats for Ringo. She once took Ringo with her to Paris, where she charmed waiters into allowing him to sit on bistro chairs and eat cheese off his own plate at the table.

The Miranda-Ringo relationship recalled her favorite fairy tale, “Beauty and the Beast.” So long as his beautiful mistress stood near, Ringo behaved with exemplary propriety. He would cooperate when Miranda maneuvered his strong paws into party costumes: an elf at Christmastime, a hot dog at Halloween. She even taught him to pose for photos. At her word, he would look at the camera and tilt his head fetchingly.

Remove her for even a minute, however, and the beast reappeared. Only Miranda could then calm him. She would scoop him up, squeeze him, and hold him in what she termed “cuddle jail.” His head would drop. His eyelids would close. He would fall asleep, snoring noisily, his furry cheek against her smooth one.

My family inherited a property on Lake Ontario from my wife’s parents. Danielle and I have spent summers there since the early ’90s. The scenery is lovely, but until recently the region offered few amusements other than nature itself. Miranda thought the place dull. But Ringo enjoyed the open spaces and the opportunity to hunt his most detested enemy: birds.

He’d awaken before dawn to bark at them through the sliding glass doors. I’d sleepily fumble with the handle, trying to grab Ringo first, because otherwise he would bite the door so hard that his teeth left marks. He would race out, pausing only to savage a plastic bucket or sink his fangs into a rubber boot—or even my leg, if I got in his way. He would rampage after the birds for half an hour, then return to gulp down his breakfast.

I once confronted Miranda about controlling his behavior. “He’s trying to warn us that we are surrounded by small flying dinosaurs,” she protested.

“Okay,” I said, “but why must he bark so much?”

“Why do you tweet?” she retorted.

At the time, Danielle and I owned two Labrador retrievers. In the summer, we would exercise them by hitting tennis balls into the lake for them to chase. Our stretch of shoreline is stony. Where lake and land meet, the water can be whipped by the wind into crashing surf. That’s no problem for an 80-pound, hard-muscled Labrador. You might expect it to daunt a little spaniel. Yet Ringo joined the game and soon became its champion. He could not swim very far, but he charged into the waves all the same, sometimes biting the rocks on his way. He would wait for one of the Labs to bring a ball closer to the shore, then seize it from them and carry it the rest of the way.

On dry ground, too, he would insist on playing fetch virtually all the long daylight hours of a Canadian summer. I would try to lock away every stray tennis ball in the place, yet Ringo would find one more, drop it at my feet, and bark at my face to demand: “Throw.”

“He won’t leave me alone,” I complained to Miranda.

“He thinks of you as his assistant,” she said.

“Well, that’s a relationship of trust at least.”

“Don’t flatter yourself. He’s a Hollywood dog; he has a lot of assistants. Mom is Assistant No. 1. You’re Assistant No. 2.”

Assistant No. 2 became my family nickname ever after.

Miranda was always nearsighted, but over the course of 2018, her vision deteriorated to the point where she could no longer read even her phone. My wife joked that she was like Marilyn Monroe’s character in How to Marry a Millionaire, the bombshell who needed glasses. But we were worried. We sent Miranda to specialists. The problem was diagnosed: a large brain tumor that was squeezing her optic nerves.

Untreated, the tumor would first blind her, then slowly kill her. But treating it would be no easy matter.

The tumor was a highly unusual kind. It was not cancerous, but it had developed its own network of blood vessels. If the tumor were excised with anything less than perfect precision, with every vessel meticulously cauterized, catastrophic bleeding into the brain could result.

My wife identified the doctor in the United States best qualified to operate on this rare and deadly threat. But how to get on his schedule? When Miranda returned from Israel, she had signed up with the least-expensive HMO she could find in California. She was only 26; how much medicine could she possibly need?

The inexpensive HMO had no intention of allowing access to the right doctor. It insisted on assigning Miranda to its in-house team. That team proposed slicing off the top of Miranda’s skull and then groping down to her brain stem. The doctors candidly confessed that the chances of success were meager.

When Danielle protested that she had found a doctor who promised a less invasive technique with a better hope of success, the HMO’s chief brain surgeon pooh-poohed her. I could have advised him that patronizing Danielle was unlikely to go well, but he kept at it. Then he addressed her as “dear.” The room exploded. “I know why you think this operation cannot be done,” Danielle said. “Since this variety of tumor was first identified in [I forget the year, but Danielle knew it], there have been [again, Danielle knew the number] successful operations in the United States. You’ve performed none of them. Maybe that’s why you misdiagnosed the tumor in the first place. The doctor we want is the only one who has even recognized it for what it is.”

The HMO never relented. Mercifully, we found an opportunity under the Affordable Care Act to shift Miranda to a different insurer that had the right doctor in its network. Miranda’s surgery was scheduled for April 2019 at Stanford University Medical Center. In the meantime, she and Ringo came to live with us in Washington, D.C.

Miranda fatigued easily that winter. It typically fell to my wife and me to walk Ringo together with the big dogs. Ringo would sprint up and down hills, plunge into muddy streams, and generally dismiss commands to “come” or “heel” as impertinent and stupid suggestions. “If Ringo was a human being,” Danielle said, “I’m not sure we’d like him very much.”

My wife and I rented an apartment in Palo Alto to be with Miranda during the preparation for the operation and the convalescence afterward. We ensured that the building was dog-friendly, so that Ringo could stay with us. The last thing Miranda needed during this period of stress and fear was responsibility for a dog ready to pick a fight with every stray leaf in his path.

But Ringo intuited that something unusual was happening in his world. This dog that normally put the high in high-maintenance abruptly reinvented himself as a wholly different animal. He quietly accompanied Miranda through every frightening minute. He attended all of her preoperative appointments, right up until the final seconds before she went in for surgery. I’d never imagined a hospital could be so sensitive to a stricken dog owner. But Stanford was, and we still feel grateful.

The doctor had warned us that the operation might take as long as eight hours. It extended to 12. No information or explanation reached us in the waiting room. Terrible thoughts crowded our minds. Our only comfort was to rub our faces in Ringo’s woolly black fur.

Then, at last, the doctor emerged. He carried a celebratory can of Coca-Cola. All had gone well. We glimpsed Miranda’s reddish-gold hair as she was pushed to the recovery room. The surgeon’s microscopic tools had traveled into the brain via Miranda’s nose. There had been no need to shave her head or crack open her skull.

We asked if we could bring Ringo into the intensive-care unit to greet Miranda when she regained consciousness. The doctor consented, but cautioned that it was very important that Miranda’s head remain in exactly the correct elevated position. There must be no disturbance, no motion. Ringo, for once in his life, complied. He lay in Miranda’s lap or on her legs. Ringo lived in the recovery room until Miranda’s release a few days later, his vigil broken only when my wife and I took him out for walks and meals.

When Miranda’s surgeon met with her before her discharge, he declared: “Now go and lead a normal life.” This was a deeply gratifying sentiment, but also not quite the truth. The tumor and the operation had ravaged Miranda’s endocrine system. She was prescribed a complex and ever-changing array of hormones for an array of needs: managing her thirst, regulating her sleep, sustaining her immune system. When COVID-19 struck, we airlifted Miranda out of Los Angeles for good. She came east wrapped in masks, scarves, and gloves. We collected her and Ringo at the airport to live with us. The year 2020 was one of the most difficult in American history for many people: lockdowns, school closures, riots, and everywhere the pall of disease. For Danielle and me, I’m a little ashamed to admit, it was one of the best times in our lives. The fledglings returned to the nest: Miranda and our son, Nathaniel, rejoined their high-school-senior sister, Beatrice.

Miranda was fiercely independent and stoic, often too independent and stoic for her own good. She had braved dangers all her life. In Israel, she smiled her way through photo sessions as Hamas rockets flew overhead. In France, when anti-Semitic thugs tried to intimidate her and some Israeli friends on the Paris subway, Miranda defiantly spoke Hebrew extra loudly. She urged self-doubting friends, “You need to say ‘fuck you’ to more people more often.” Always ready to listen to the troubles of others, she adamantly refused to discuss her own. But for those months, Miranda, for once in her life, let us take care of her as she preferred to take care of others.

Beatrice postponed college for a year and remained with us through the fall. Ten years older, Miranda regarded Beatrice as something of a daughter, as well as a sister. The two of them spent hours in each other’s rooms, laughing and gossiping and planning future adventures, watching movies together long after Danielle and I fell asleep.

The bird life in our wooded part of Washington, D.C., may be even more active than in the open fields of Ontario. Years ago, Danielle and I added a second-story balcony off our bedroom. A sparrow family built a nest in the eaves above. Ringo interpreted that domestic act as a personal affront and a violent intrusion. He would leap into the air to snap and bark at the nest, either on the balcony deck or, when restrained, through the bedroom’s glass door. Then, at last, Ringo’s hour of triumph: In one of his lunges, he caught a young bird as it lifted from its nest and killed it. Miranda pretended to share the family horror, not very convincingly.

The pandemic passed. Miranda rented an apartment in New York, on the sixth floor of a building in SoHo where the ancient elevator had long ago stopped working. Every time she went in or out, Ringo also had to climb all six floors, each step almost as tall as he was. The exercise bulked up his muscles and sinews. Picking him up to stop him from attacking things became even more challenging than before. He could wriggle and twist with all the power of an athlete who executes hundreds of push-ups a day.

On a visit to that apartment, Nathaniel observed another side of Ringo’s character. Miranda inflated an air mattress for Nat to use as a bed. Early one morning, Nat awoke to see Ringo engaged in passionate motion with the edge of the mattress. “Maybe we should get Ringo a real girlfriend?” Nat asked Miranda.

The dream of normality seemed to have come true. We celebrated family milestones: birthdays, holidays, Nat’s wedding. Miranda and Ringo moved again, to Brooklyn, this time to a building with an elevator. Ringo befriended all the doormen. One day, he bolted into the elevator ahead of Miranda—and the doors closed. Miranda was frantic, imagining the elevator opening in the lobby and Ringo darting into the street. But within moments, the elevator returned. There stood a doorman, grinning, Ringo in his arms.

Miranda and Ringo explored their new borough together. In her neighborhood, America’s worsening drug-addiction problem could be witnessed on every sidewalk, unconscious bodies slumped on curbs and benches. Beautiful, clever, and privileged as she was, Miranda always identified with society’s misfits and outcasts. She habitually carried an extra water bottle with her to tuck under a street sleeper’s arm to be discovered when he awoke. Ringo would glare disapprovingly, but this was one circumstance in which his wishes did not prevail.

The day after Valentine’s Day this year, my wife had big news for Miranda. She knew that Miranda had always wanted to take Ringo to London, but had been deterred by the British embargo on bringing in pets without lengthy and costly quarantining. Danielle had discovered a work-around and wanted to share it with Miranda. But the conversation never took place. Through the winter, Miranda had suffered a series of bad colds; getting her on the phone had become hard. I texted her, but unusually for her, no swift answer came.

The next morning, February 16, we received the devastating news that Miranda had been found dead in her Brooklyn apartment. Illness overwhelmed her depleted immune system and stopped her heart. She collapsed at about three in the morning. When she was found, Ringo was lying beside her.

For me, the thought of my own death has never been a distressing subject. We live, we love, we yield the stage to our children. I hoped that when the time arrived, I would have the chance for farewells. If that wish were granted, I could with total content ride the train to my final destination. It never occurred to me that one of my children might board the train first, pulling away as her parents wept on the platform.

But so it happened. All the end-of-life decisions that my wife and I had expected to deliberate for ourselves now had to be made at breakneck speed for our cherished daughter. We would bury her at a small, rural Jewish cemetery a short distance from our Ontario home. That way, we could be near her for the rest of our lives, then beside her ever afterward.

Transporting a body from one country to another is never an easy matter. Everything about the process becomes more difficult when the person has died at the beginning of a three-day weekend. My brother-in-law Howard, a successful businessman, stepped in with an enormously generous act of assistance: He chartered a plane to carry Miranda from New York to Toronto.

Wrapped in a blanketed body bag, Miranda was laid on a bench in the aircraft, then buckled in. My wife and I sat opposite her, with Ringo on a leash. As the plane gained altitude, Ringo jumped on Miranda’s chest. He lay there for a long time, then sidled toward her legs, then to her feet. As the flight came to an end, Ringo hopped off Miranda and into my wife’s lap, as if to say, “I belong with you now.” He posted himself beside Miranda’s coffin at the funeral in Toronto. He gazed into the grave as Miranda was lowered into the ground. Then he meekly departed with us.

When a parent loses a child, the nights are the worst. Thoughts come crashing into the mind: every missed medical clue, every pleasure needlessly denied, every word of impatience, every failure of insight and understanding. Like seasickness, the grief ebbs and surges, intervals of comparative calm punctuated by spasms of racking pain. I don’t want to wake my wife, who has a grief schedule of her own, so I slip out of our bed and into the one Miranda used when she stayed with us in Washington. When I do that, Ringo will climb up to sleep at my feet, just as he slept on Miranda’s that one last time.

Immediately after Miranda died, Ringo did not like anyone else to hold him. At first, I deferred to his resistance. Then I remembered something my sister, Linda, said during the most difficult phase of Miranda’s never-easy adolescence: “Sometimes the kid who seems to want the hug the least is the kid who needs the hug the most.” I experimented with my own version of “cuddle jail.” After a few attempts, Ringo accepted the embrace, then welcomed it.

And I think: Over 32 years of life, Miranda gave me many gifts. She gave me joy, and pride, and the wisdom that can be learned only from loving another being more than one loves oneself. Then, at the end, she gave me one last gift, the most immediately necessary of them all. She left me the means to expiate all those sins of omission and commission that crowd my mind at three in the morning. She left me Ringo. For better or worse, I will be Assistant No. 2 to the very end of his days, or mine.

This article appears in the May 2024 print edition with the headline “Miranda’s Last Gift.”

What's Your Reaction?