Mark Robinson Is Testing the Bounds of GOP Extremism

If he loses, the Republicans have a problem. If he wins, they also have a problem.

A decade ago, Mark Robinson had a dead-end job and a nasty habit of posting anti-Semitic, homophobic, and sexist screeds on Facebook. Today he is North Carolina’s lieutenant governor. This November, he could become the state’s first Black governor.

“There is a REASON the liberal media fills the airwaves with programs about the NAZI and the ‘6 million Jews’ they murdered,” Robinson wrote on Facebook in 2017. “There is also a REASON those same liberals DO NOT FILL the airwaves with programs about the Communist and the 100+ million PEOPLE they murdered throughout the 20th century.” He also blasted the movie Black Panther as “created by an agnostic Jew and put to film by satanic marxist [sic],” adding, “How can this trash, that was only created to pull the shekels out of your Schvartze pockets, invoke any pride?” He had a recurring bit about Michelle Obama being a man. He said Beyoncé’s music sounds like “satanic chants.” He’s no less inflammatory offline, where he has called homosexuality “filth” and endorsed corporal punishment for children.

These views are awful but hardly unusual. What is unusual is that the man professing them won North Carolina’s Republican primary for governor in March. He will face Josh Stein, a Democrat and the current state attorney general, in November. Robinson’s fringe positions have led some to assume that he can’t win, but polls indicate that the race is very close. Robinson could reshape the politics of North Carolina, which has tried in recent years to attract newcomers from around the country. He also provides a test of how extreme a MAGA Republican can be and still win office outside deep-red states—of what, if anything, is too extreme in contemporary politics.

[David Frum: The GOP is just obnoxious]

Robinson declined multiple requests for an interview, but I read his memoir, Facebook posts, and statements, and spoke with North Carolina political insiders, to understand how he went from anonymity to the top of the party’s ticket in less than a decade. His rise is reminiscent of Donald Trump’s: Republican leaders thought they could use him for their ends, but he had his own vision. Should he lose, the GOP will miss out on a seat that a generic Republican could have won. Should he win, Republicans will have the challenge of dealing with Governor Robinson.

Back in the days before his political rise, Robinson’s Facebook friends mostly responded to his political opinions with semi-affectionate eye-rolling or annoyed sniping. These interactions might have been a nice distraction from Robinson’s bleak prospects in his job: In 2014, the office-furniture company Steelcase announced that the plant in High Point, North Carolina, where Robinson worked would soon close. He still carries a note he wrote on an employee suggestion card: “At 12:02 on 7/15/15, I sat at my desk at Steelcase and wondered what I would be doing in 5 years.”

The moment that answered that question came three years later. In April 2018, following the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting, the Greensboro City Council considered canceling a local gun show. Robinson, then employed unloading trucks and moving finished furniture, delivered a stem-winder in defense of gun rights at the council’s meeting.

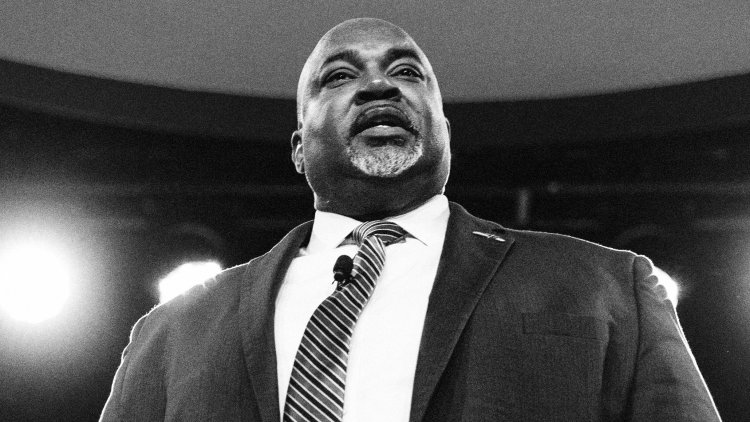

“I didn’t have time to write a fancy speech,” said Robinson, a gregarious mountain of a man with a shaved head, a neatly trimmed beard, and a broad drawl. He may have been nervous, but he showed a natural talent for public speaking. “What I want to know is, when are you all going to start standing up for the majority?” he said. “And here’s who the majority is: I’m the majority. I’m a law-abiding citizen who’s never shot anybody, never committed a serious crime, never committed a felony.”

Representative Mark Walker, a North Carolina Republican, shared the speech on Facebook, and it went viral. Three days later, Robinson was on Fox News talking about gun rights. Soon, Republicans were pushing Robinson to use his newfound fame to run for office in 2020.

He was an unusual recruit: He’s Black in a very white party. He is an unapologetic culture warrior in a diversifying and purple state. He is also a blue-collar worker in a country (and party) where most candidates and officials are well-to-do. But grassroots conservatives and party officials urged him to stand for lieutenant governor. His viral moment showed his politics and his ability to get attention. The lieutenant governor of North Carolina doesn’t have many formal duties, so the self-appointed adults in the party would remain in control.

The plan worked, at first: Robinson defeated his Democratic opponent, even though the Republican lost the governor’s race. As lieutenant governor, Robinson has frequently missed meetings of the state Senate, over which he nominally presides, and of the state board of education, on which he sits. His signature initiative, an inquiry into supposed indoctrination in state public schools, seemingly broke open-records laws and then quietly issued a report that was merely a compendium of vague and unsubstantiated anecdotes. (Robinson’s office contends that the commission wasn’t a “public body” subject to transparency laws.) Regardless, Robinson took advantage of the soft power of his office to raise his profile like no lieutenant governor before.

By the time he declared his candidacy for the GOP gubernatorial primary, Robinson was a strong favorite, despite the deep reservations of many Republican leaders. He defeated Dale Folwell, a staid old-school conservative who has served as state treasurer for years. Walker, the representative who’d shared Robinson’s city-council speech, had broken with Robinson and launched a campaign for governor, but got nowhere. A well-funded late-game attempt by the attorney Bill Graham fell short too. Now Robinson is the Republicans’ standard-bearer, like it or not.

Robinson’s rise has perplexed many observers. State GOP leadership, perhaps shy after an anti-trans law backfired, has tended toward more traditional right-wing legislative goals—restricting voting rights, siphoning funds away from public schools, and undoing environmental regulations—than the loudly antagonistic culture war that Robinson wages. For example, Robinson has repeatedly called abortion “murder” and proposed a total ban; GOP leaders in the legislature have denied they want to ban abortion outright and have sought to present their limitations as a “compromise.” But Robert Korstad, a historian at Duke University, told me that although Robinson is an outlier today, he’s a throwback to the state’s previous notoriously conservative national figure.

“He's a contemporary Jesse Helms in many ways, just this kind of bombast,” Korstad said, referring to the late U.S. senator. “Helms said things that were equally vicious and off the wall for many years, going back to the 1950s, so it fills a gap in North Carolina politics that has been there for a long time.”

Although Helms railed against elites, he was a white man from a prominent small-town family, attended the prestigious Wake Forest University, and rose to prominence working at a newspaper and a Raleigh news station. Robinson, by contrast, had a poor and violent childhood in Greensboro, didn’t finish his degree until 2022, and rode social media to political stardom. No prior North Carolina governor and no sitting governor in the United States went straight from a blue-collar job to that office.

The Duke political scientist Nicholas Carnes has calculated that working-class people have never constituted more than 2 percent of Congress, and they currently represent roughly the same portion of state legislatures. Carnes concludes that this is because blue-collar people are simply not running, given the time and financial burdens of campaigning and a lack of recruitment by parties. “Working-class Americans are less likely to hold office for some of the same basic reasons that they’re less likely to participate in politics in other ways: because often they can’t, and nobody asks them,” he writes in his book The Cash Ceiling.

Robinson’s politics are conservative but idiosyncratic and not always coherent. He complains that red tape made it difficult for his wife to manage a day care, but he has demanded more intrusive state regulation of what teachers can and can’t say in the classroom. He rails against “government ‘charity,’” but his wife’s nonprofit received $57,000 in Paycheck Protection Program cash. He preaches fiscal conservatism, but declared personal bankruptcy three times, failed to file taxes for five years, and lost a house to foreclosure. (This is a delicate issue for opponents to bring up, because it may endear Robinson to voters who relate to living in a precarious financial situation.) He laments being bullied by classmates as a child for being poor—“They had all adopted a superior attitude toward me for something I could not help”—but doesn’t seem to empathize with other marginalized people, including LGBTQ people, who may well have had comparable experiences.

His views are atypical among working-class voters, too. Blue-collar voters support a stronger social safety net, more business regulation, more progressive tax policies, and more worker protections. These are typically Democratic goals, but even working-class Republicans are also far more supportive of welfare programs, government health care, and business regulations, and more opposed to income inequality, than Republican business owners, Carnes notes. Robinson is on the other side of each of these issues.

Under Trump’s leadership, the Republican Party has made some inroads with white working-class voters. Robinson has sought to bind himself to Trump, though the former president was notably slow to endorse his would-be protegé. He finally gave Robinson the nod just three days before the primary election, somehow catching Robinson’s rivals by surprise. “Looking at his remarks, he seems unaware that he’s endorsing a lawless, AWOL individual who denies the Holocaust, hates women and continues to fleece the taxpayers and donors of North Carolina,” his opponent Folwell posted on X. (The irony that Trump matches much of that description seems to have been lost on Folwell.)

When Trump endorsed Robinson, he inevitably labeled him “Martin Luther King on steroids.” That’s especially cringey because Robinson has criticized Martin Luther King Jr. Day and called King an “ersatz pastor” and a “Communist.” Most Black voters in North Carolina, like those nationally, are heavily Democratic—a fact usually attributed to Democratic support for civil rights. (Four years ago, 92 percent of them supported Joe Biden, according to exit polls.) Some Republicans have argued for years that Black voters hold more conservative views than their voting record would suggest, and that they could be amenable to advances from Republicans. In 2020, Trump made small but significant gains among Black men. Robinson writes in his memoir, We Are the Majority, that he’d accepted the received wisdom in the Black community that Rush Limbaugh was a racist until a friend goaded him into giving the radio host a shot. Robinson found himself nodding along with Limbaugh’s ideas.

Republicans hope that Robinson can bring along more Black voters. His attacks on the civil-rights movement may complicate that. “So many freedoms were lost during the civil-rights movement,” he said in 2018. He has also criticized the famous sit-in at a Woolworth’s in his hometown (“That’s not what you do in a free-market system”) and blamed Communist provocateurs for a 1979 Ku Klux Klan shooting that killed five people in Greensboro.

Robinson’s views more closely echo southern white working-class politics than any strain of Black conservatism, Jarod Roll, a historian of working-class politics at the University of Mississippi, told me. He pointed to Robinson’s affinity for guns, his religiosity, and his emphasis on traditional gender roles. Like Robinson, many workers across North Carolina lost jobs as the textile and furniture industries closed factories or moved them offshore. Among them, Black voters have mostly remained with the Democratic Party, if they vote, while many white ones have moved toward the GOP.

“I don't think he's representative of a new brand of Black conservatives,” Theodore Johnson, a senior adviser at the liberal think-tank New America who studies Black politics, told me. “Robinson is a very particular kind of Black Republican, and it’s a version that’s more partisan than it is ideological, more sensational than it is substantive.”

Minority candidates who tack to the far right, like Robinson, have experienced notable success in the Republican Party since 2008. They may not attract many voters of color, but their conservative views validate them in the eyes of voters who might otherwise assume that, because of their skin color, they are moderates or liberals, Johnson said. At the same time, he said, their race may serve to disarm accusations of racism against the GOP.

This past October, Robinson was acting governor while Governor Roy Cooper, a Democrat, traveled to Japan. Robinson announced a press conference, setting the North Carolina political world abuzz over what he had in mind. Would he announce some major initiative or try to overturn some of Cooper’s policies? Was this some sort of coup?

Robinson arrived at the legislative building in Raleigh flanked by a clutch of young male staffers and wearing the Trump uniform of a boxy suit with a red tie. His big news, it turned out, was a day of prayer and solidarity with Israel following the October 7 attacks. The announcement was plainly intended to neutralize Robinson’s past remarks about Jews, but he seemed unprepared for questions.

“There have been some Facebook posts that were poorly worded on my part and did not convey my real sentiments,” he said, later adding, “I apologize for the wording, not necessarily for the content.” The answer was nonsense: What would it mean to regret the wording but not the content of the claim that Black Panther was a ploy by Jews to take money from Black people?

In his book, Robinson had offered a different excuse: “I was a private citizen. I had a right to say it. You may not like it, but that’s the way it works.” He’s right: He had a right to say it, and many people may not like it. The sophistry illustrates Robinson’s dilemma. He’s risen to prominence thanks to a freewheeling style and far-right views that could turn off the swing voters and moderate Republicans he needs to win.

Democrats in North Carolina, like Democrats everywhere, plan to make abortion central to this year’s campaign. Robinson has in recent months tried to soft-pedal his position. Rolling Stone reported that he’s said that he’s avoiding “the a-word.” His team, wary of Robinson going off script, has granted mainstream media outlets few interviews with him. That may be the only way to keep him from making inflammatory remarks. As with Trump, separating the crazy from the charisma is difficult.

“There’s no danger of Mark Robinson being boring,” Chris Cooper, a political scientist at Western Carolina University (and no relation to the governor), told me. “You could put him in a tweed coat and give him a cup of chamomile, and he’s still going to be engaging.”

[Derek Thompson: The Americans who need chaos]

Josh Stein, Robinson’s Democratic opponent in the governor’s race, is less dynamic. He’s racked up consumer-protection victories in office and cleared a long-standing rape-kit backlog, but altough Stein has styled himself as a successor to the popular Cooper, he lacks the governor’s drawl and common touch. He also hails from Chapel Hill, long derided by conservatives like Helms as a den of dangerous liberalism, and he would be the state’s first Jewish governor.

Republicans hope that the race shapes up like the 2016 presidential election, with voters taking a chance on an unorthodox conservative over a plodding progressive. Although Biden’s campaign says it plans to compete in North Carolina, Republicans expect the president’s unpopularity to dampen Democratic-voter enthusiasm. Democrats prefer to look to the 2022 Pennsylvania governor’s race, in which Attorney General Josh Shapiro defeated MAGA Republican Doug Mastriano by emphasizing his opponent’s extremism, as a template. Stein and progressive allies have stockpiled money for what’s expected to be a brutal offensive against Robinson.

“I see Mark Robinson as a problem for Republicans in North Carolina across the board,” Paul Shumaker told me. A longtime strategist for more traditional Republicans, Shumaker worked for Robinson’s opponent Graham during the primary. According to Shumaker, Stein and his allies will benefit from the fact that the most effective attacks on Robinson are all quotations of things he has said, which could overcome typical voter skepticism about claims made in attack ads. “They’ll have him destroyed by Labor Day,” he said. “Then you start going downballot and start making him a liability for people who hitched a wagon to him.”

Polling suggests that Robinson’s support is already suffering as the barrage begins, though Robinson still has a good chance to win, especially if Trump takes the state by a good margin. (The former president won in North Carolina in both 2016 and 2020.) Shumaker’s point that Robinson is the Democrats’ own best messenger against himself reminded me of a passage in his memoir. Robinson was at a Junior ROTC drill meet in high school when his team was crossing some railroad tracks to get pizza. When a train approached, his comrades wisely moved off the tracks, but Robinson lingered as the engineer laid on his horn. Finally, Robinson jumped—barely dodging the Amtrak, which was moving much faster than the trundling freight that he’d expected.

Robinson waited in a ditch just long enough to convince his friends he’d been killed, then popped out to surprise them. Some were so angry at his prank that they wanted to beat him up: “They’d all thought I was a goner. So, for a moment, did I.”

It’s a strange story—the sort of anecdote that might have seemed pretty funny to a 14-year-old, but is a little weird for an adult to be repeating in a barroom or barbershop in his sixth decade. It’s even weirder for a politician to include in a campaign autobiography, but Robinson sees a moral. “Obviously I don’t condone it,” he wrote. “Yet that energy within me and the desire to take chances, once harnessed to sane and proper ends, have served me well in adulthood.”

Everyone’s entitled to a little youthful indiscretion. The problem in Robinson’s case is that he hasn’t given North Carolinians much reason to believe he’s found those sane and proper ends yet—or ever will.

What's Your Reaction?