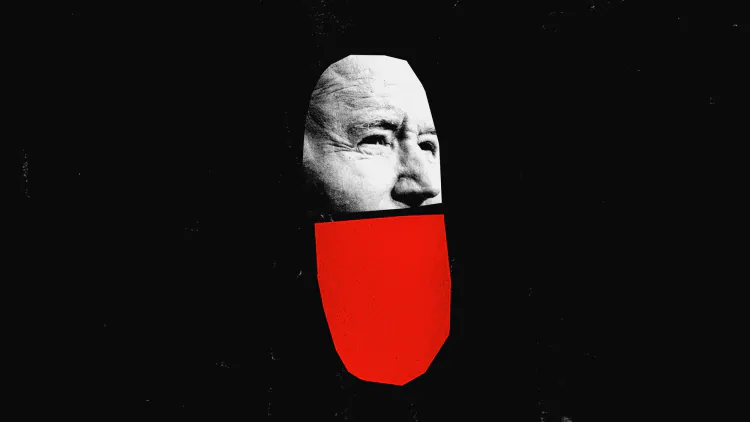

Joe Biden’s Drug-Price Conundrum

The president turned one of the most popular ideas in politics into reality. So far, no one seems to care.

Suppose the president asked you to design the ideal piece of legislation—the perfect mix of good politics and good policy. You’d probably want to pick something that saves people a lot of money. You’d want it to fix a problem that people have been mad about for a long time, in an area that voters say they care about a lot—such as, say, health care. You’d want it to appeal to voters across the political spectrum. And you’d want it to be a policy that polls well.

You would, in other words, want something like letting Medicare negotiate prescription-drug prices. This would make drugs much more affordable for senior citizens—who vote like crazy—and, depending on the poll, it draws support from 80 to 90 percent of voters. The idea has been championed by both Bernie Sanders and Joe Manchin. Turn it into reality, and surely you’d see parades in your honor in retirement communities across the country.

Except Joe Biden did turn that idea into reality, and he seems to have gotten approximately zero credit for it. Tucked into the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 was a series of measures to drastically lower prescription-drug costs for seniors, including by allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices. And yet Biden trails Donald Trump in most election polls and has one of the lowest approval ratings of any president in modern American history.

In that respect, drug pricing is a microcosm of Biden’s predicament—and a challenge to conventional theories of politics, in which voters reward politicians for successful legislation. Practically nothing is more popular than lowering drug prices, and yet the popularity hasn’t materialized. Which raises an uncomfortable question: Politically speaking, does policy matter at all?

High drug prices are not a fact of nature. In 2018, the average list price of a month’s worth of insulin was $12 in Canada, $11 in Germany, and $7 in Australia. In the U.S., it was $99. America today spends more than seven times per person on retail prescription drugs than it did in 1980, and more than one in four adults taking prescription drugs in the U.S. report difficulty affording them.

Short of direct price caps, the most obvious way to address the problem is to let Medicare—which, with 65 million members, is the nation’s largest insurer—negotiate prices with drug manufacturers. Just about every other rich country does a version of this, which is partly why Americans pay nearly three times more for prescription drugs than Europeans and Canadians do. Price negotiation would slash costs for Medicare beneficiaries, while cutting annual federal spending by tens of billions of dollars.

The pharmaceutical industry argues that lower prices will leave companies with less money to invest in inventing new, life-saving medicines. But the Congressional Budget Office recently estimated that even if drug companies’ profits dropped 15 to 25 percent as a result of price negotiation, that would prevent only 1 percent of all new drugs from coming to market over the next decade.

[Ezekiel J. Emanuel: Big Pharma’s go-to defense of soaring drug prices doesn’t add up]

Medicare drug-price negotiation has nonetheless had a tortured three-decade journey to becoming law. Bill Clinton made it a central plank of his push to overhaul the American health-care system, an effort that went down in flames after a massive opposition campaign by all corners of the health-care industry. Barack Obama campaigned on the idea but quickly abandoned it in order to win drug companies’ support for the Affordable Care Act. In 2016, even Donald Trump promised to “negotiate like crazy” on drug prices, but he never did.

Joe Biden accomplished what none of his predecessors could. The Inflation Reduction Act is best known for its clean-energy investments, but it also empowered Medicare to negotiate prices for the drugs that seniors spend the most money on. In February of this year, negotiations began for the first 10 of those drugs, on which Medicare patients collectively spend $3.4 billion out of pocket every year—a number that will go down dramatically when the newly negotiated prices come into effect. The IRA will also cap Medicare patients’ out-of-pocket costs for all drugs, including those not included on the negotiation list, at $2,000 a year, and the cost of insulin in particular at $35 a month. (In 2022, the top 10 anticancer drugs cost a Medicare patient $10,000 to $15,000 a year on average.) And it effectively prohibits drug companies from raising prices on other medications faster than inflation. “Right now, many people have to choose between getting the care they need and not going broke,” Stacie Dusetzina, a cancer researcher at Vanderbilt University, told me. “These new policies change that.”

Yet they don’t seem to have caused voters to warm up to Biden. The president’s approval rating has remained stuck at about 40 percent since before the IRA passed, lower than any other president at this point in their term since Harry Truman. A September AP/NORC poll found that even though more than three-quarters of Americans supported the drug-price negotiation, just 48 percent approved of how Biden was handling the issue of prescription-drug prices. A similar dynamic holds across other elements of the Biden agenda. In polls, more than two-thirds of voters say they support Biden’s three major legislative accomplishments—the IRA, the CHIPS Act, and the bipartisan infrastructure bill—and many individual policies in those bills, including raising taxes on the wealthy and investing in domestic manufacturing, poll in the 70s and 80s.

All of this poses a particular challenge for the “popularism” theory. After Biden barely squeaked by Donald Trump in 2020, an influential group of pollsters, pundits, and political consultants began arguing that the Democratic Party had become associated with policies, such as “Defund the police,” that alienated swing voters. If Democrats were serious about winning elections, the argument went, they would have to focus on popular “kitchen table” issues and shut up about their less mainstream views on race and immigration. Drug-price negotiation quickly became the go-to example; David Shor, a political consultant known for popularizing popularism, highlighted it as the single most popular of the nearly 200 policies his polling firm had tested in 2021.

One obvious possibility for why this has not translated into support for the president is that voters simply care more about other things, such as inflation. Another is that they are unaware of what Biden has done. A KFF poll from December found that less than a third of voters knows that the IRA allows Medicare to negotiate drug prices, and even fewer are aware of the bill’s other drug-related provisions. Perhaps that’s because these changes mostly haven’t happened yet. The $2,000 cap on out-of-pocket costs doesn’t come into effect until 2025, and the first batch of new negotiated prices won’t kick in until 2026. Or perhaps, as some popularists argue, it’s because Biden and his allies haven’t talked about those things enough. “I’m concerned that Democrats are dramatically underperforming their potential in terms of talking about healthcare policy and making healthcare debates a salient issue in 2024,” the blogger Matthew Yglesias wrote in October.

When I raised this critique with current and former members of the Biden administration, the sense of frustration was palpable. “The president is constantly talking about things like lowering drug prices and building roads and bridges,” Bharat Ramamurti, a former deputy director for Biden’s National Economic Council, told me. “We read the same polling as everyone else. We know those are popular.” He pointed out that, for instance, Biden has spoken at length about lowering prescription-drug prices in every one of his State of the Union addresses.

The problem, Ramamurti argues, is that the press doesn’t necessarily cover what the president says. Student-debt cancellation gets a lot of coverage because it generates a lot of conflict: progressives against moderates, activists against economists, young against old—which makes for juicy stories. The unfortunate paradox of super-popular policies is that, almost by definition, they fail to generate the kind of drama needed to get people to pay attention to them.

Both sides have a point here. It’s true that Biden’s drug-pricing policies have received relatively little media coverage, but it’s also up to politicians and their campaigns to find creative ways to generate interest in the issues they want people to focus on. Simply listing policy accomplishments in a speech or releasing a fact sheet about how they will help people isn’t enough. (The same problem applies to other issue areas. According to a Data for Progress poll, for example, only 41 percent of likely voters were aware as of early March that Biden had increased investments in infrastructure.)

[Ronald Brownstein: Americans really don’t like Trump’s health-care plans]

For the White House, the task of getting the word out may become easier in the coming months, as voters finally begin to feel the benefits of the administration’s policies. The cap on annual out-of-pocket drug costs kicked in only at the beginning of the year (this year, it’s about $3,500, and it will fall to $2,000 in 2025); presumably some Medicare-enrolled voters will notice as their medication costs hit that number. In September, just in time for the election, Biden will announce new prices for the 10 drugs currently being negotiated.

Another assist could come from efforts to stop the law from taking effect. Last year, multiple pharmaceutical companies and industry lobbying groups filed lawsuits, many in jurisdictions with Trump-appointed judges, to prevent Medicare from negotiating drug prices; meanwhile, congressional Republicans have publicly come out against the IRA overall and drug-price caps in particular. As the failed effort to repeal the Affordable Care Act in 2017 showed, few things rally support for a policy like the prospect of it being taken away.

The more pessimistic outlook is that voters’ impressions of political candidates have little to do with the legislation those candidates pass or the policies they support. Patrick Ruffini, a co-founder of the polling firm Echelon Insights, pointed out to me that, in 2020, when voters were asked which presidential candidate was more competent, Biden had a nine-point advantage over Trump; today Trump has a 16-point advantage. “I don’t know if there’s any amount of passing popular policies that can overcome that,” Ruffini said.

That doesn’t make the policy stakes of the upcoming election any lower. If he’s reelected, Biden wants to expand Medicare’s drug negotiation to 50 drugs a year and extend the out-of-pocket spending caps to the general population. Trump, meanwhile, has said he is going to “totally kill” the Affordable Care Act and that he intends to dismantle the IRA. There’s some drama for you. Whether it will get anyone’s attention remains to be seen.

What's Your Reaction?