Is Kara Swisher Tearing Down Tech Billionaires—Or Burnishing Their Legends?

She has long sought to be the best-connected of the tough reporters and the toughest of the insiders. Balancing those goals isn’t always easy.

Few journalists and their sources have fallen out as completely as Kara Swisher and Elon Musk. The reporter met the future billionaire in the late 1990s, when she was a tech correspondent for The Wall Street Journal and he was just another Silicon Valley boy wonder. Over more than two decades, they developed a spiky but mutually useful relationship, conducted through informal emails and texts as well as public interviews.

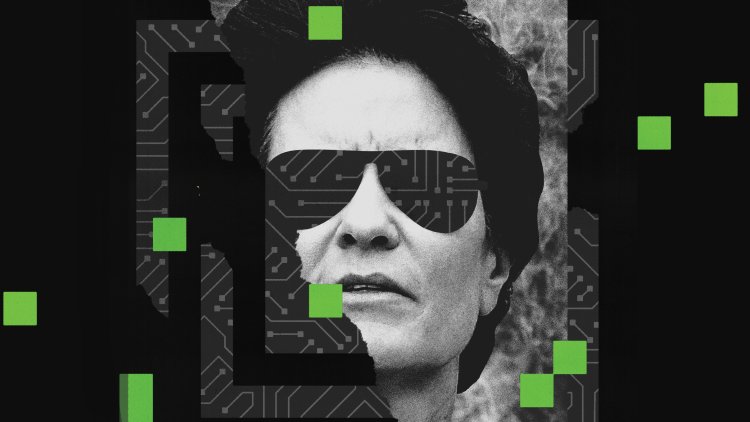

Their frenemy shtick was on display, for example, when Swisher interviewed Musk for Vox on Halloween in 2018. He deadpanned that he loved her “costume.” She was wearing her signature look—black leather jacket, black jeans, aviator sunglasses presumably just out of view. “Thank you! I’m dressed as a lesbian from the Castro in San Francisco,” she replied. The pair posed together for a photograph: him seated and her standing, one arm casually resting on his shoulder, an image that signaled she was more than a mere stenographer or grateful supplicant. She was a Silicon Valley player in her own right.

That image illustrates the pact that Swisher has developed with so many masters of the tech universe ever since she began to cover (and champion) the industry. She would be tough and inquisitive, asking the types of blunt questions about screwups and misfires that these supposed visionaries rarely faced in their heavily gatekept existence. They would parry her blows with charm, self-deprecating humor, and—occasionally—unwise honesty or unwitting self-exposure. Both would derive some benefit. At a minimum, the tech overlords would get credit for stepping into the gladiatorial arena. The audience benefited, too, from Swisher acting as our eyes and ears inside an industry that was changing our lives.

For a time, Musk was Swisher’s dream subject, hanging in the sweet spot of the arc that bends from “unknown visionary” through “eccentric millionaire” onward to “compulsive poster of cringe memes and conspiracy theories.” In 2016, at her Code Conference, he made headlines by predicting that SpaceX would be sending people to Mars within a decade. Another 2018 interview for Vox generated headlines as Musk endorsed Donald Trump’s idea of a Space Force. In 2020, he and Swisher discussed AI doomerism for The New York Times.

Then Musk took over Twitter and started treating it as his own digital fiefdom, replacing a flawed content-moderation system with one that could fairly be summarized as “whatever Elon feels like today.” Elite opinion turned against him, and with somewhat less alacrity, so did Swisher: She decided that the quirky entrepreneur had become an isolated dictator surrounded by yes-men—and by then he’d stopped taking her calls. The pair’s souring relationship played out on Musk’s own platform, now rebranded as X, and elsewhere. She tweeted out a defense official’s quote criticizing Musk’s threat to cut off funding for Starlink, his satellite system, in Ukraine. For that, Musk sent her an email calling her an “asshole.” She later called him a “petty jerk.” He subsequently said she should “take it easy on the Adderall—foaming at the mouth is just not a good look.”

[Read: Elon Musk is bad at this]

Swisher blames the fallout on his descent into “adult toddler mode” and more dangerous territory beyond that. (In November, Musk replied to a post on X pushing an anti-Semitic conspiracy theory with “You have said the actual truth.”) Most journalists would mourn their loss of access to a key source, but Swisher has used the incident to freshen her signature image as a journalistic pit bull. Her new memoir, Burn Book: A Tech Love Story, is part of that project. It opens with two pages titled “Praise for Kara Swisher,” which she has peppered with insults from her enemies. Musk is the only person to get two entries: “Kara Swisher’s heart is filled with seething hate” and “Kara has become so shrill at this point that only dogs can hear her.”

Is the drama between Musk and Swisher entirely real, a reflection of her wider disenchantment with the tech industry? Or is it as mutually beneficial as their previous coziness? Good luck working that out. On Musk’s side, you have volatility, self-regard, and neurodivergence (he used his Saturday Night Live monologue in 2021 to talk about his autism). On Swisher’s side, you have ego and professional pride, as well as brand maintenance: After Musk made a bid for Twitter, she took heat as an “apologist” for his ever more erratic behavior. As late as April 2022, she said in an interview that he was “quite complex” and that people underestimated him. “I really have been very supportive of Elon, even when he’s acted badly sometimes,” she said during her podcast On With Kara Swisher in November of that year. “I get dragged a lot for that.” Now that they are no longer on speaking terms, she denounces him with the zeal of a convert.

The uneasy symbiosis between writer and subject is a thread that runs through Burn Book, elevating it above a gossipy romp (which it also is). Silicon Valley has posed a coverage challenge since the beginning. Its denizens have expected tech journalists to be advocates of an emerging industry against an older generation of Luddite unbelievers. The story has been about boy geniuses who must be excused from following normal rules of behavior, or sometimes even the law, because they need to be free to “disrupt.” In reporting on this scene, Swisher, as a woman born in the early ’60s, found herself cast in a quasi-maternal role that has sharpened her eventual disappointment with the hollowness of its idealism. “While my actual son filled me with pride,” she writes, “an increasing number of these once fresh-faced wunderkinds I had mostly rooted for now made me feel like a parent whose progeny had turned into, well, assholes.”

[From the March 2024 issue: Adrienne LaFrance on the rise of techno-authoritarianism]

Swisher didn’t always want to be a journalist. She’d hoped to join the U.S. military, but as a lesbian, she couldn’t, because of its ban on openly gay personnel. She graduated from college in 1984, a decade before even the pathetic Clinton-era compromise of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. Swisher never wanted to be in the closet: “I wanted them to ask, and I was compelled to tell.”

Becoming an intelligence analyst would have allowed her to follow in her father’s military footsteps. Louis Bush Swisher rose to be a lieutenant commander in the Navy before dying suddenly of a brain aneurysm at 34, when Kara was 5. In place of the gentle, smiling man she remembers only through photographs, she got a rich stepfather whom she “came to think of as a villain,” ready with “casual cruelties.” This kind of childhood ordeal is common among people with extraordinary drive later in life; Swisher shares the experience of a terrifying paternal figure with Musk, who says his father, Errol, was emotionally abusive (Errol has denied the accusation).

Her start in journalism set the tone for her career. As a student at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service, she called The Washington Post to complain that an article about a speech on campus was full of inaccuracies. She bickered with the editor involved, who dared her to come argue in person (she did), and then hired her as a campus stringer. She went to journalism school, but found it a waste of time, was turned down for multiple jobs, and lasted less than a year at the Washington City Paper before being fired. In her breakout role ghostwriting John McLaughlin’s National Review column, she refused to run errands for him, mocked him openly in a meeting, and later went on the record alleging that he had sexually harassed a co-worker. His response to that brave act also makes the “Praise for Kara Swisher” section at the front of Burn Book : “Most people in this town stab you in the back, but [Kara] stabbed me in the front, and I appreciate that.”

By the ’90s, she had landed at the Post, where she records being the only one interested in the newsroom’s recently acquired cellphone. At 34, she went west to San Francisco. The man-childishness of Silicon Valley is by now a well-rehearsed theme, but Swisher’s vignettes of juvenile weirdness are still astonishing. At a baby shower in 2008 for the Google co-founder Sergey Brin, guests were invited to dress as infants, with costumes supplied at the door: “Wendi Deng, then the wife of News Corp titan Rupert Murdoch (whom I had taken to referring to as ‘Uncle Satan’), had chosen a diaper and sucker combo.” That’s the kind of sentence that demands to be read twice.

A beat reporter to her core, Swisher doesn’t cover the Valley’s arrested development as an anthropologist would—and anyway, she isn’t sure the “man-boys” who “felt half-formed and opaque to me with no discernible edge or interesting bits” merit such attention. (In 2019, Musk brought a stuffed monkey to a “serious discussion” about the future of the media with the publisher of The New York Times, A. G. Sulzberger, and chatted to it during the meeting.) She does observe, though, that perpetual adolescence explains what she calls “the grievance industrial complex.” Again and again, her subjects project the air of a teenager slamming the door to their room, protesting that it’s all so unfair. “Tech is littered with men whose parents—typically fathers—were either cruel or absent,” she writes. “By the time they grew to be adults, many were unhappy and often had some disgruntled tale of being misunderstood before they were proved triumphantly right.”

[Read: The journalist and the fallen billionaire]

Swisher is the perfect journalist to chronicle these men. She clearly relishes jousting with arrogant males, and she shares the inner drive that propels and torments them. She is also, like them, fiercely entrepreneurial—a rule-breaker and a risk-taker. After the dot-com crash, she lost patience with her employer’s lack of interest in the digital future, and went into business with her friend Walt Mossberg, whose pioneering “Personal Technology” column for The Wall Street Journal began in 1991. They persuaded Dow Jones to back an enterprise called D: All Things Digital. She and Mossberg would combine their reporting with an events business, trying to skirt the dangers of such undertakings—that they’re “fanboy gatherings (complicit) or sponsor-driven pitches (conflicted),” in Swisher’s words; either way, they’re boring. Tech speakers at All Things Digital, which debuted in 2003, would get no fees or even travel expenses, and they wouldn’t be shown interview questions in advance. “No one could hide on our stage, including us.”

Swisher boasts that her career was built on a single insight she adopted early: Everything that can be digitized will be digitized. The one thing that cannot be, she and others understood, is IRL proximity to greatness—or, at least, to wealth and influence. This is at once smart and ethically challenging. How do you attract rich, powerful interviewees when all you have to offer is questions they might get in trouble for answering—and when you’re dealing with a club whose members, though they “like to gather and swagger,” are not used to being contradicted? If you’re Swisher, you get cozy with the stars.

In Burn Book, she openly acknowledges this criticism, in an attempt to defuse it. Swisher wants to be the best-connected of the tough reporters, and the toughest of the insiders. She argues that All Things Digital made news that hardly flattered her speakers: Mark Zuckerberg’s appearance in 2010, when her co-host, Mossberg, grilled him about privacy, was largely memorable for his “increasing moistness” under the stage lights. She urged him to remove his Facebook hoodie; he declined. Finally he gave in, at which point she threw him a lifeline by shifting attention from his damp armpits to the mission statement—“Making the world more open and connected”—printed inside the hoodie. “Omigod. It’s like a secret cult,” she joked. The fact that, despite the terrible headlines, Zuckerberg sent her a thank-you note afterward—and that Swisher makes sure to mention this in her memoir—neatly demonstrates the ambiguity of her position.

In a similar spirit, Burn Book is full of moments when Swisher describes finding herself in the role of unpaid adviser to people she’s also reporting on—showing both her influence and her attempts to set boundaries. Murdoch, apparently unbothered by her nicknaming him Uncle Satan, calls her to fish for dirt on his rivals and solicit her thoughts on ventures such as investing in Vice Media. “(Please don’t, I advised; he did it anyway.)” She phones Yahoo’s co-founder Jerry Yang in the early 2000s to warn him about keeping a Google search box on his homepage: “ ‘You need to get them off your platform,’ I said regarding the dangerous licensing deal. ‘They look harmless, but they’ll kill you.’ ” (He didn’t listen.) Google’s Larry Page asks her for help writing an essay about the company’s mission. (She declines.) Writing about the private female-focused networking events that Sheryl Sandberg hosted for a time, she calls attention—consciously or not—to the impotence that a supposedly independent Valley reporter can feel. Sandberg often made a point of conscripting Swisher to deliver hardballs to the other attendees to break the ice, only to follow up with an “ ‘oh-that’s-Kara-what-can-I-do’ shrug” when the interviewees got flustered. This vignette leaves Swisher looking less like a pit bull and more like a Chihuahua.

The message that the time has come for some distance from Silicon Valley hasn’t been lost on Swisher, who has established a base in Washington, D.C., where she bought a home several years ago. A quarter century after the dot-com boom, she notes, democracy still hasn’t caught up with digital technology: “I have spent an increasing amount of time talking to government officials and legislators in recent years, since no significant U.S. laws have been passed to rein in tech … ever.” Podcasts have become her primary journalistic outlet, and she hosts a punishing four episodes every week. The tech industry certainly generates enough big questions to justify this diligence: Should AI companies be allowed to plunder copyrighted works to train their large language models? Has the U.S. allowed too much power to become concentrated in the hands of a small cadre of men in hoodies? How should crypto be regulated?

Swisher’s tech boosterism once distinguished her from other journalists. Her newfound disillusionment puts her squarely in the middle of the consensus—try finding a commentator who doesn’t think that Silicon Valley “disrupters” need to be given firmer boundaries. But old habits die hard. In March 2021, she suggested that making fun of the non-fungible-token craze was a mistake because “there is underlying value to owning the tweet that Jack Dorsey started Twitter with.” Funny story: A year later, the Dorsey-tweet NFT—which had sold for $2.9 million in 2021—went on sale again. After a week, the top bid was … $277. It didn’t have much “underlying value” at all. Swisher might have gone sour on the tech bros, but like them, she is sometimes too starry-eyed about anything that calls itself progress.

This article appears in the April 2024 print edition with the headline “The Insider.”

What's Your Reaction?