Inside the Decision to Kill Iran’s Qassem Soleimani

I carried out the drone strike on the ruthless general. America still doesn’t understand the lesson of his death.

Any assessment of the Middle East’s future must contend with an unpleasant fact: Iran remains committed to objectives that threaten both the region and U.S. interests. And those objectives are coming within reach as the country’s ballistic-missile arsenal and air-defense systems grow, and its drone technology improves.

All of this was on display last month, when Iran launched a barrage of missiles and drones at Israel. No lives were lost—the result of not only Israel’s capable defenses but also the contributions of U.S. and allied forces. The attack showed that America’s continued presence in the region is crucial to dissuade further aggression. But our current policy isn’t responsive to this reality. U.S. military capabilities in the Middle East have steadily declined, emboldening Iran, whose leverage strengthens as international support for Israel wanes. Moreover, America’s clear desire to draw down in the region has undermined our relationships with allies.

Recent history demonstrates that a strong U.S. posture in the Middle East deters Iran. As the leader of U.S. Central Command, I had direct operational responsibility for the strike that killed Qassem Soleimani, the ruthless general responsible for the deaths of hundreds of U.S. service members. Iran had begun to doubt America’s will, which the strike on Soleimani then proved. The attack, in early 2020, forced Iran’s leaders to recalculate their months-long escalation against U.S. forces. Ultimately, I believe, it saved many lives.

[Read: Is Iran a country or a cause?]

The situation in Iran has changed, but the Soleimani strike offers a lesson that is going unheeded. Iran may seem unpredictable at times, but it respects American strength and responds to deterrence. When we withdraw, Iran advances. When we assert ourselves—having weighed the risks and prepared for all possibilities—Iran retreats. Soleimani’s life and death are a testament to this rule, which should guide our future policy in the Middle East.

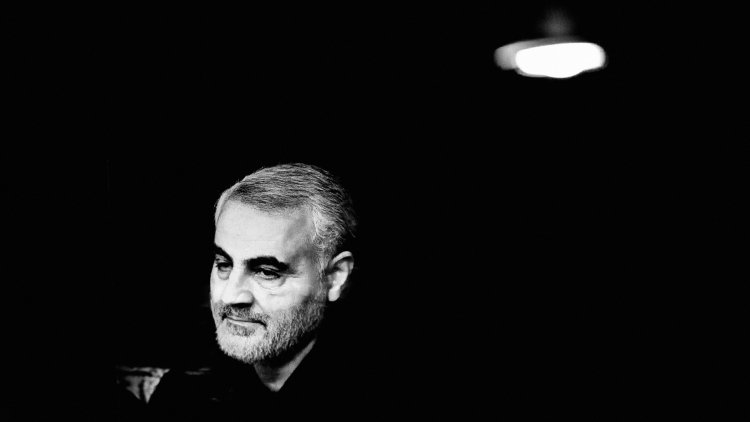

Soleimani is a central character in the modern history of U.S.-Iran relations. Over 30 years, he became the face of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), a distinctly independent branch of the armed forces tasked with ensuring the integrity of the Islamic Republic. Soleimani joined the IRGC in 1979, one year before Saddam Hussein invaded Iran. In the ensuing war, Soleimani developed a reputation as fearless and controlling, rising to the rank of division commander while still in his 20s. He emerged from the war with a bitter disdain for America, whose aid to Iraq he blamed for his country’s defeat.

In 1997 or 1998, Soleimani became the commander of the Quds Force, an elite group within the IRGC that focuses on unconventional operations beyond Iran’s borders. Soleimani was indispensable in its development, relying on his charisma and fluent Arabic to expand Iran’s influence in the region. As commander, Soleimani had a direct line to Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, becoming like a son to him. He was promoted to major general in 2011 and by 2014 was a hero in Iran, having been the subject of an extensive New Yorker essay. I often heard a story—perhaps apocryphal—about a senior official in the Obama administration plaintively asking an intel briefer, “Can’t you find a picture of him where he doesn’t look like George Clooney?”

As Soleimani’s fame grew, so did his ego. He became dictatorial, acting across the region often without consulting other Iranian intelligence entities, the conventional military, or even the larger IRGC. He shrewdly supported the return of American forces to Iraq, prompting the U.S. to do the heavy lifting of defeating the Islamic State. Then he drove us out of Iraq, killing U.S. and coalition service members, as well as innocent Iraqis and Syrians, with staggering efficiency. In his mind, he was untouchable: Asked about this in 2019, he replied, “What are they going to do, kill me?”

When I first joined Centcom as a young general, I watched the Obama administration—and the Bush administration before that—fail to counter the dynamism and leadership that Soleimani brought to the fight. I also watched the Israelis try their hand against him with no luck. So when I took over as commander in March 2019, one of the very first things I did was inquire if we had a plan to strike him, should the president ask us to do so. The answer was unsatisfying.

I directed Centcom’s joint special operations task force (JSOTF) commander to develop solutions. Other organizations were interested in Soleimani as well—including the CIA and regional partners—and we saw evidence that some of them had lobbied the White House to act against him. Several schemes were debated and set aside, either because they weren’t operationally feasible or because the political cost seemed too great. But they eventually grew into suitable options if the White House directed us to act.

Beginning two months into my tenure as commander, and continuing through mid-December 2019, American bases in Iraq were struck 19 times by mortar and rocket fire. Soleimani was clearly orchestrating the attacks, principally through his networks within Kataib Hezbollah, a radical paramilitary group in Iraq. The series of strikes culminated on the evening of Friday, December 27, when one of our air bases was hit by some 30 rockets. Four U.S. service members and two Iraqi-federal-police members were injured, and a U.S. contractor was killed. Whereas the previous attacks had been intended to annoy or to warn, this attack—launched into a densely populated area of the base—was intended to create mass casualties. I knew we had to respond.

Early the next morning, key members of my staff crowded into my home office, in Tampa, to review a range of options that we had been refining for months. This was all anticipatory; the authority to execute an attack could come only from President Donald Trump through Mark Esper, the secretary of defense, but we knew they would want us to present them with choices. We had a target in Yemen that we had been looking at for some time: a Quds Force commander with a long history of coordinating operations against U.S. and coalition forces. Other possible targets included an intelligence-collection ship crewed by the IRGC in the southern Red Sea—the Saviz—as well as air-defense and oil infrastructure in southern Iran.

After all of the options were thoroughly debated, I told my staff that we would recommend targets only inside Iraq and Syria—where we were already conducting military operations—to avoid broadening the conflict. We felt that four “logistics targets” and three “personality targets” were associated with the strike. Two of the personalities were Kataib Hezbollah facilitators; the third was Soleimani. We would also forward but not recommend action on the Yemen, Red Sea, and southern-Iran options.

By mid-morning, I had sent my recommendations to Secretary Esper through Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. By late afternoon, we’d received approval to execute my preferred choice: striking a variety of logistics targets but not Soleimani or the facilitators.

We would strike the next day, Sunday, after which Esper and Milley would brief Trump at Mar-a-Lago. Milley had suggested to me that Trump might not think the attacks were enough. I knew how those meetings worked—I’d been in a few of them—and I had complete confidence in Milley. He could hold his own in the rough-and-tumble of a presidential briefing, which often featured lots of opinions from lots of people, not all of whom knew the full risks involved in an operation or those that would emerge after it was completed.

Because I knew the president remained very interested in Soleimani, on Saturday evening I put my final edits on a paper that outlined what could happen if we chose to strike him. There was no question that he was a valid target, and his loss would make Iranian decision making much harder. It would also be a strong indication of U.S. will, which had been absent in our dealings with Iran for many years. But I was extremely concerned about how Iran might respond. The strike could have a deterring effect, or it could trigger a massive retaliation. After careful consideration, I believed that they would respond but probably not with an act of war—a possibility that had worried me for many years. But they still had lots of alternatives to cause us pain. I sent the paper to the secretary, routed through the chairman. I did not recommend against striking Soleimani, but I described the risks it entailed.

[Read: Qassem Soleimani haunted the Arab world]

We flew the Kataib Hezbollah strikes on Sunday afternoon with good results. We struck five sites across Syria and Iraq all within about a four-minute span. In at least one location, we struck during a Kataib Hezbollah staff meeting, killing several key leaders. After the strike, as Esper and Milley flew to Mar-a-Lago, we provided them with damage assessments and any other details we could gather from the attacks. We put together a simple one-slide presentation that Milley used to brief the president.

The chairman called that evening with a report on the briefing. As Milley had warned, Trump wasn’t satisfied; he instructed us to strike Soleimani if he went to Iraq. I was in my home office when Milley relayed this. My staffers were crammed around me, but I didn’t have the phone on speaker, so none of them could hear. I froze for a second or two, then asked him to repeat himself. I’d heard correctly.

Milley also told me that the president had approved strikes on the Quds Force commander in Yemen and on the Saviz, Iran’s ship in the Red Sea. There was a sense in the meeting, he said, that these strikes would bring Iran to the bargaining table. I could tell that the chairman did not agree with this position—and neither did I. We felt the strikes might restore deterrence, but we didn’t see a path to broader negotiations.

As we ended our call, I read back to the chairman what we’d been told to do—a product of a lifetime of receiving orders under stressful conditions. I called in the few members of my staff who weren’t already on hand for a 7 p.m. meeting. Everyone’s head snapped back just a little when I told them our instructions. We all knew what could come from these decisions, including the possibility that many of our friends on the other side of the world would have to go into the fire. We didn’t have time to dwell on it.

I knew that we could execute quickly on the Saviz and the commander in Yemen, but Soleimani was a more challenging target. In late fall, we had developed options to strike him in both Syria and Iraq. We preferred Syria; a strike against him in Iraq would inflame the Shiite militant groups, possibly resulting in a strong military and political backlash. It now looked like those concerns, which I knew the chairman shared, would be overridden.

The kind of targeting we were pursuing has three steps: finding, fixing, and finishing. Finding is a science, but fixing—translating all we know about the target’s movements and habits into a narrow window of time, space, and opportunity—is an art. Finishing, too, is an art: hitting a target while keeping collateral damage to an absolute minimum.

The Soleimani fix and finish solutions had come a long way since I’d first inquired about them in the spring. We now knew that when Soleimani arrived in Iraq, he typically landed at Baghdad International Airport and was quickly driven away. Thankfully traffic was often light on the airport’s access road, which generations of soldiers, airmen, and Marines knew as “Route Irish,” its military designation during the Iraq War. Quite a few U.S. and coalition service members had died on it thanks to Soleimani and his henchmen. The fix part of the equation grew complicated when Soleimani got off Route Irish and entered the crowded streets of Baghdad.

Striking Soleimani in the moments after he deplaned would also likely minimize collateral damage. We would use MQ-9 uncrewed aircraft armed with Hellfire missiles to attack his vehicle and that of his security escort. As always, there were significant constraints—the MQ-9s couldn’t stay above the airport for too long, so we had to know roughly when he would arrive. Our preference was to execute at night, with no cloud cover, but to some extent we were at the mercy of Soleimani’s schedule.

We had information suggesting that he would fly from Tehran to Baghdad on Tuesday, December 31. After much discussion, we decided to strike Soleimani first and then, within minutes, the commander in Yemen, so that he couldn’t be warned. We decided to save the Saviz for later; I wasn’t eager to sink it (and fortunately, we wouldn’t have to).

Meanwhile, protests began to develop at our embassy in Baghdad in response to the Kataib Hezbollah strikes. The images were disturbing and seemed to harden the desire in Washington to strike Soleimani. The specter of a Benghazi-like episode underlined everything we did. We ordered in Marines for added security and put AH-64 gunships overhead in a show of force. I grew more worried about what could happen after we hit Soleimani. Would it spur the crowd to try to overrun the embassy? What would our relationship with the Iraqi government look like in the aftermath of an attack?

[Read: Iran is not a ‘normal’ country]

I sensed that the National Security Council—which includes the secretaries of state and defense, and the national security adviser—was operating under the view that Iran would not retaliate against the United States. Even Milley told me, “The Shia militant groups will go apeshit, but I don’t think Iran will do anything directly against us.” I disagreed. To his great credit, the chairman understood my arguments and made sure we were prepared if it did.

I went into Centcom headquarters early on December 31, the day we hoped to strike. The morning wore on while we waited for signs of Soleimani’s movement. Two huge monitors hung on the far wall. One showed a rotating series of black-and-white images from the MQ-9s. The other showed the hundreds of planes, including civilian airliners, that were crossing Iraq and Iran.

Soleimani finally left home and boarded a plane in Tehran, though we weren’t sure if the flight was chartered or commercial. The jet took off at about 9:45 a.m. ET for a two-hour flight to Baghdad. We were ready for him: Our aircraft were overhead and in good positions. When his plane approached Baghdad, however, it didn’t descend. I was on a conference call with Milley and Secretary Esper as we watched it pass the city at 30,000 feet.

Someone from the Pentagon asked me, “Can you shoot this fucker down?” Without deciding to execute the request, I called my air-component commander in Qatar. “If I give you an order to shoot this aircraft down, can you make it work?” The Air Force responded quickly, and we moved two fighters into a trail position behind the jet. We now had an option in hand to finish the mission if we were told to do so. We worked feverishly to determine if the flight was chartered or commercial.

It soon became apparent that the plane was headed to Damascus. We also learned that the jet was a much-delayed civilian flight, meaning at least 50 innocent people were probably on board. I immediately advised Milley that we should not shoot. Not even Soleimani was worth that loss of life. He and I quickly agreed that we would not engage. Our fighters rolled off, and the jet began its descent into Damascus. We also pulled back our aircraft from the mission in Yemen. We all took a deep breath and reconsidered our options. “Guidance from the president remains,” I told the staff and commanders at 10:48 a.m. “We’re going to take a shot when we have a shot.”

There were indications that Soleimani would travel from Damascus back to Baghdad in the next 36 hours. We still had another opportunity.

New Year’s Day came. I had an obligation in Tampa to deliver the game ball for the Outback Bowl. My security and communications teams came with me. The day was nearly cloudless; I hoped it would be in Baghdad too. The game went well—if you were cheering for Minnesota. We were among the Auburn faithful, so it was a long afternoon.

Before halftime, I received a call from Esper. I spent most of the second half on the phone with him and Milley, crouching in the suite’s bathroom, talking on a secure handset as my communications assistant stood outside the door, holding a Wi-Fi hotspot in the air. I told them that our latest intelligence suggested that Soleimani would leave Damascus soon, as early as the next day, and fly to Baghdad. The call ended in time for me to watch the end of a very disappointing game. It was a restless night.

The next day, I went to Centcom headquarters. By late afternoon, tension had begun to build. The flight we expected Soleimani to take was delayed an hour, and then another. I sat quietly at the head of the table and drank copious amounts of coffee. Everyone is looking at the commander during times like this; I knew that any unease on my part would be felt by all. I was confident that we were prepared, but many things were outside our control, and we would need to be ready to adapt. The countless hours that staff members and commanders had put into contingency planning were now ready to pay off. Time turns against you in these moments. It becomes compressed and precious. You need to rely on the work done before time becomes the most valuable commodity in the universe.

Finally, movement! Soleimani was delivered to the airplane in Damascus, boarding from the tarmac. The jet backed out and taxied for takeoff. The flight, a regularly scheduled commercial jet, took off from Damascus at 3:30 p.m. ET. I called the chairman. He and the secretaries of defense and state would monitor the action from a secure conference room in the Pentagon. The aircraft soon appeared on our tracking systems, and I watched it crawl east. Remembering our disappointment of a few days before, I kept a close eye on the altitude. Thankfully the plane began descending over Baghdad, landing at 4:35 p.m., shortly before midnight local time.

It was cloudy. Our MQ-9s flew low to maintain visibility, which meant they initially had to stay some distance away to avoid being heard or seen. We watched as stairs were rolled up to the front cabin door. At 4:40 p.m., we confirmed that it was Soleimani. My JSOTF commander called me and said, “Sir, things will now happen very quickly. If there’s any intent to stop it, we need to make that call now.” I had my orders, so I simply told him, “Take your shot when you have it.”

We watched Soleimani get into a car and pull away alongside a security vehicle. They began to negotiate the warren of ramps, parking areas, and streets to get to Irish. It was now 4:42 p.m. I had long since passed the authority to strike to the JSOTF commander, and he had further passed it down to the team that would release the weapons. Hard experience had taught us that devolving this authority to the lowest possible level as early as possible allowed for those with the best knowledge of the situation to act quickly, without referring back to headquarters.

The two vehicles picked up speed. Everyone’s eyes were glued to the big monitors. No one spoke. Then, suddenly, a great flash of white arced across the screen. Pieces of Soleimani’s car flew through the air. After a second or two, the security vehicle was struck. There was no cheering, no fist-bumping—just silence, as we watched the cars go up in flames. A minute later, we attacked again, dropping eight more weapons. The operation appeared to be a success, but we couldn’t yet confirm.

We had another target to attack, so our attention shifted to Yemen, where we carried out a similar strike on an isolated house where we believed the Quds Force commander to be. We later determined that we’d missed him, but the timing of the two strikes—13 minutes apart—was a remarkable achievement.

Soon it became clear that we had gotten Soleimani. I was home by about 9 p.m., when the first news reports started to appear. Only then did I have time to think about what had happened.

The decision to strike Soleimani was made by Trump, who was getting input from his advisers that Iran would not retaliate, a view that no one at Centcom or in the intelligence community shared. That didn’t mean the strike was unwarranted; it meant we weren’t sanguine about the aftermath.

[Eliot A. Cohen: Iran cannot be conciliated]

In the end, I believe that the president made the right decision. Had Soleimani not been stopped, more U.S., coalition, and Iraqi lives would have been lost as the direct result of his leadership. I believe more attacks were likely to happen in the immediate future. Soleimani wasn’t going to undertake them himself, but they would inevitably follow his trip to Iraq. The risk of inaction was greater than the risk of action.

Iran had doubted our ability to demonstrate such force, and for good reason—we had never done so over the course of at least two administrations. Now, for the first time in many years, Iran had seen the naked power of the United States. It had to recalculate. Small-scale attacks continued, particularly those that couldn’t be directly attributed to Iran. But operational guidance to both Iranian forces and their proxies had changed: Avoid major attacks on U.S. forces. This was a watershed moment in the U.S.-Iran relationship.

Striking Soleimani showed Iran a kind of resolve that had long been absent from U.S. policy. This cycle played out again last month, when Iran attacked Israel: American engagement countered Iranian aggression.

If we plan to remain in the Middle East, we must be prepared to show that same resolve. The risk of escalation is inevitable but manageable; it is the refusal to accept this risk that has hobbled our policy for so long. The lessons of the Soleimani strike are clear, and we shouldn’t forget them. The Iranians will respect our strength. They will take advantage of our weakness.

This article has been adapted from Kenneth F. McKenzie Jr.’s new book, The Melting Point: High Command and War in the 21st Century.

What's Your Reaction?