How ‘the End’ Helps Us Find New Beginnings

Contemplating death at the start of a new year

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

You have a plethora of metaphors to pick from when describing these early days of 2025. January is a phoenix rising from the ashes; a butterfly wriggling free of its chrysalis. If you like, picture a bouncing baby New Year in your arms, powder fresh. The images all amount to the same thing: January is a time to (metaphorically) turn the page. But during a week of tragedy and chaos that doesn’t necessarily bode well for new beginnings, I’ve been thinking instead about December and the figurative language we use to describe the close of the year—the kind that focuses on death and decay. The days smolder and are snuffed out; the old man of 2024 grows frail and creaky, and he shuffles to his grave.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

- “Bridge of the Gods,” a poem by Ansel Elkins

- Five books that offer readers intellectual exercise

- “Birthmark,” a poem by L. A. Johnson

My thoughts might be lingering on endings more than usual because the year 2025 feels surreal. We’ve advanced beyond the far-off futures of Neon Genesis Evangelion’s rebuilt 2015 Tokyo; Blade Runner’s cyberpunk 2019 Los Angeles; Star Trek’s paradigm-shifting 2024 Bell Riots in San Francisco; and the cracked-up 2024 California of Parable of the Sower, as Ilana Masad notes today. None of those imagined 21st-century settings is particularly pleasant—their creators believed that humanity would persist, but sometimes just barely, and certainly under bleak conditions. The urge to picture a frightening—even apocalyptic—future is not uncommon, Adam Kirsch points out in an essay this week. He quotes T. S. Eliot’s 1925 poem “The Hollow Men,” which closes on “the way the world ends / Not with a bang but a whimper.” A century later, these lines remain relevant. “The dread of extinction has always been with us; only the mechanism changes,” Kirsch writes.

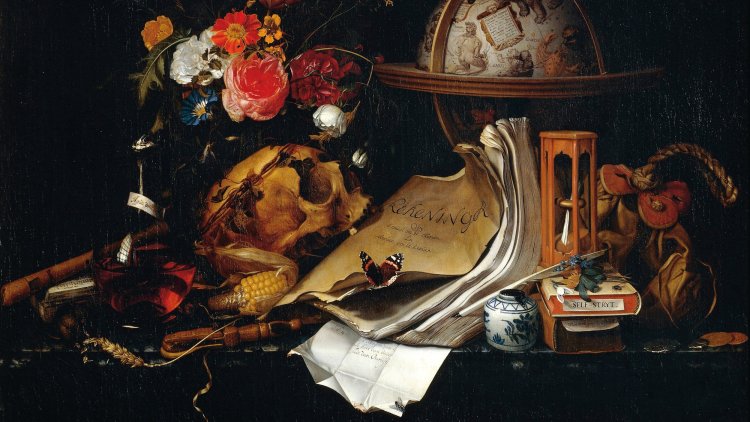

His article provides an overview of artists’ long-running, wide-reaching fascination with End Times, but I find the theme oddly resonant at this time of year. I read some poetry on Wednesday to mark the season (the Poetry Foundation has curated a nice collection). In Richard Hoffman’s short, affecting “December 31st,” the speaker pins the new year’s calendar to the wall. January’s image is “a painting from the 17th century, / a still life: Skull and mirror, / spilled coin purse and a flower.” This is recognizable as a memento mori, a work of art meant to remind the viewer of the brevity of life and the inevitability of death. The flower is beautiful today, but soon it will wilt; the coins are spilled because you can’t take wealth with you. The truth is darkly ironic—we cannot contemplate rebirth without remembering mortality.

At the beginning of the year, we tend to think about rejuvenation in individual terms, by making resolutions for self-improvement and personal growth. Conversely, I wonder if we sublimate dread of our own individual extinction by imagining a broader apocalypse. If the world collapses entirely, we won’t have to consider that it might continue turning without us. On good days, I actually find that thought comforting, or at least I try to: Even when I’m gone, there will continue to be new years I won’t see. These bracing January days can be an opportunity to contemplate both death and rebirth—and to do something about it. I can take advantage of the short time allotted to me and work to become a better person, partner, and friend; my task is made meaningful, and urgent, by the fact that my days are numbered.

Apocalypse, Constantly

By Adam Kirsch

Humans love to imagine their own demise.

What to Read

Small Things Like These, by Claire Keegan

Keegan’s novella follows an Irishman, Bill Furlong, delivering coal throughout a small town during a lean 1980s winter. The story unfolds in the days before Christmas, a time when Bill finds himself particularly moved by the mundane, beautiful things in his life: a neighbor pouring warm milk over her children’s cereal; the modest letters his five daughters send to Santa Claus; the kindness his mother was shown, years earlier, when she became pregnant out of wedlock. While bringing fuel to the local Catholic convent, however, Bill discovers that women and girls are being held there against their will, forced to work in one of the Church’s infamous “Magdalene laundries.” He knows well, in a town defined by the Church, why he might want to stay quiet about the open secret he’s just learned, but it quickly becomes clear that his morals will make him unable to do so. Although the history of Ireland’s treatment of unmarried women and their children is violent and bleak, the novella, like Bill’s life, is characterized by ordinary, small moments of love. — Amanda Parrish Morgan

From our list: Six books to read by the fire

Out Next Week

What's Your Reaction?