Bringing a Social Movement to Life

The author Adam Hochschild recommends books that vividly illustrate moments of great change.

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

Occasionally you read a book that changes your sense of what a book can do. For me, that title was Adam Hochschild’s King Leopold’s Ghost, which recounts the history of Belgium’s brutal colonial rule over the Congo and how an early-20th-century human-rights campaign managed to bring world attention to the atrocities taking place in the name of profit. I went on to read all of Hochschild’s other books, and each one achieved the same difficult feat: bringing narrative flair to the story of a movement, whether the 19th-century abolitionist struggle in England or the republican cause taken up by Americans in the Spanish Civil War. What Hochschild does is not easy. He uses the conventions of a fiction writer to make the push for human rights extremely readable. It was a thrill to have him write an essay this week on a new book by David Van Reybrouck, Revolusi: Indonesia and the Birth of the Modern World, about that nation’s independence struggle—Hochschild says the book “fills an important gap.” I took the opportunity to talk with Hochschild about some other books he’d recommend, especially those focused on moments in history when people manage to accomplish great change.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

- Would limitlessness make us better writers?

- What the author of Frankenstein knew about human nature

- “My Book Had Come Undone”: a poem by Carolina Hotchandani

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Gal Beckerman: Besides your own work, what are some books you recommend that do a good job presenting the dynamics of activism and making change?

Adam Hochschild: One of my favorite books—and one of the great nonfiction works of the 20th century—is George Orwell’s Homage to Catalonia. In 1936, Orwell volunteered in the Spanish Civil War to fight fascism. But once in Spain, he found two things he didn’t expect: the most far-reaching social revolution Western Europe has ever seen, and a war-within-the-war as other parties in the Spanish Republic crushed these changes. No reader can forget Orwell’s description of what it feels like to be hit by a bullet: like being “at the center of an explosion.”

Beckerman: The book you reviewed exposed me to Indonesia’s independence movement for the first time, I’m ashamed to admit. Are there any books that did that for you—opened you up to a new part of the world or a history you didn't know about?

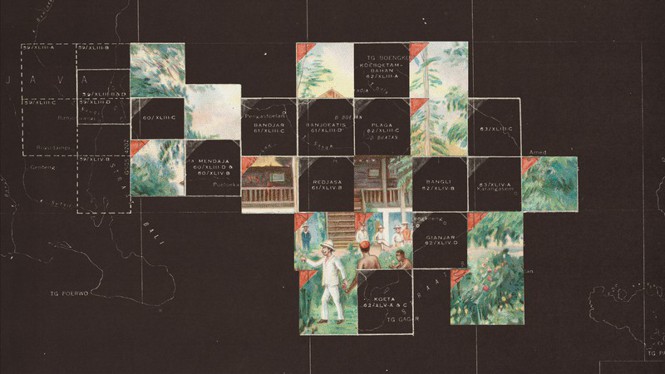

Hochschild: One piece of history I long knew too little about was the Philippine War of 1899–1902. Gregg Jones’s Honor in the Dust: Theodore Roosevelt, War in the Philippines, and the Rise and Fall of America’s Imperial Dream is a good narrative introduction. And Vestiges of War: The Philippine-American War and the Aftermath of an Imperial Dream 1899–1999, edited by Angel Velasco Shaw and Luis H. Francia, is an extraordinarily rich collection of documents, photographs, film scripts, poetry, and more.

Beckerman: Are there works of fiction that you think offer an important lens on human rights?

Hochschild: If Not Now, When? is the best of the two novels by the great Italian writer and Auschwitz survivor Primo Levi, who devoted most of his writing life to nonfiction about the Holocaust. John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath is an unforgettable portrait of human suffering in the Great Depression, and Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, set in a meatpacking plant, gave us the Pure Food and Drug Act. However, that was not the intention of Sinclair, who was more concerned about labor rights. “I aimed at the public’s heart,” he said later, “and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”

Beckerman: Finally, do you have one book you might press on a young writer looking to work in the same narrative-nonfiction vein as you?

Hochschild: To me, Robert Caro is our greatest living nonfiction writer. Start with his first book, The Power Broker, about New York City’s parks and the highway czar Robert Moses. You don’t have to be a native New Yorker like me to appreciate this massive demolition job on the man who laced our glorious city with ugly freeways and had a lifelong contempt for Black and poor people. It’s a masterpiece of storytelling and one of the best books about the exercise of power ever written.

The Particular Cruelty of Colonial Wars

By Adam Hochschild

A new history of Indonesia’s fight for independence reveals the brutal means by which the Dutch tried to retain power.

What to Read

Multiple Choice, by Alejandro Zambra, translated by Megan McDowell

If you’ve ever taken a standardized test in your life, you’ll recognize the format of the Chilean writer Zambra’s book immediately. The author grew up under the Pinochet dictatorship, and in this work, based on the structure of the Chilean Academic Aptitude Test, he uses multiple-choice questions, fill-in-the-blanks, and long sample texts to confront the authoritarian instincts that underlay his own education and that continue in many rigid, exam-based educational systems today. Its many questions begin to create a creeping sense of dread and nihilism, and that mood comes to a head in the last section, which is made up of three short stories and a series of questions about each. Yet even with these dark undertones, the book is both a quick read and hilarious. You may have thought that you never wanted to encounter fill-in-the-bubble-type tests again, but rest assured, Multiple Choice does all the work for you; it’s brilliant, and well worth your time. — Ilana Masad

From our list: Six cult classics you have to read

Out Next Week

???? Mean Boys, by Geoffrey Mak

???? The Unexpected: Navigating Pregnancy During and After Complications, by Emily Oster and Nathan Fox

???? Silk: A World History, by Aarathi Prasad

Your Weekend Read

We’re All Reading Wrong

By Alexandra Moe

The ancients read differently than we do today. Until approximately the tenth century, when the practice of silent reading expanded thanks to the invention of punctuation, reading was synonymous with reading aloud. Silent reading was terribly strange, and, frankly, missed the point of sharing words to entertain, educate, and bond. Even in the 20th century, before radio and TV and smartphones and streaming entered American living rooms, couples once approached the evening hours by reading aloud to each other.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Explore all of our newsletters.

What's Your Reaction?