American Politics Has an Age Problem

At its core, this is an issue of honesty.

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

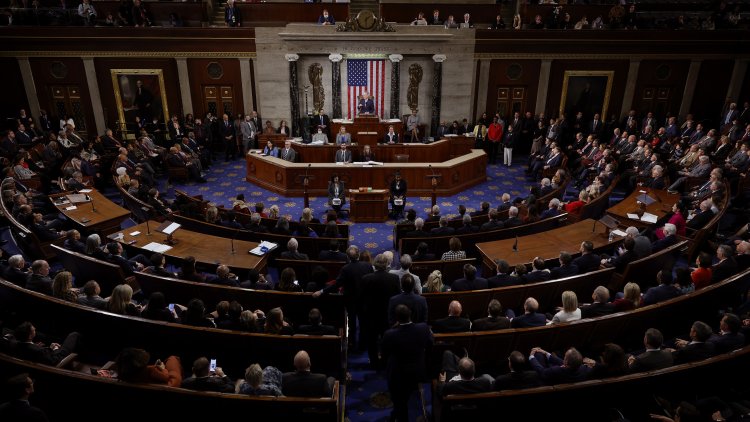

A senior GOP representative from Texas vanished from Congress for five months. Kay Granger, who is 81 years old, stepped down as chair of the House Appropriations Committee this past spring, and she announced last year that she would not seek reelection. Sometime in July, she disappeared from Congress entirely and has since missed months’ worth of votes.

Last week, The Dallas Express (whose now-CEO mounted a primary challenge against Granger in 2020) reported that Granger has been residing in an assisted-living facility. Her son soon confirmed that she has lived there for at least several months; yesterday, he reportedly said that the representative’s decline was “very rapid,” and that she’d moved into the facility before she’d begun showing signs of dementia. In a statement to Axios, Granger said, “Since early September, my health challenges have progressed making frequent travel to Washington both difficult and unpredictable.” Yesterday, her staff posted a picture of the representative; it’s unclear how many of her colleagues knew about her condition.

Once again, the moral questions of America’s political gerontocracy reveal themselves. This is an especially sensitive subject, because so many of us have loved ones—parents, grandparents, siblings—who are in cognitive decline. They deserve our consideration, compassion, and honesty. That’s also true for members of Congress, Supreme Court justices, and presidents. But the stakes there are much higher, and in those cases, sometimes compassion means being truthful about when it’s time to move on.

As the Granger story reminds us, having a politician stay in their role even while suffering cognitive decline is damaging to those who rely on them. Constituents and local officials in Texas seemed stunned to learn that their representative had vanished. State Republican Executive Committeeman Rolando Garcia said it was a “sad and humiliating way” for Granger to end her career. “Sad that nobody cared enough to ‘take away the keys’ before she reached this moment,” he wrote on X. Did Granger’s staff and family cover for her? Did they mislead the public? Did they lie to Granger herself? How hard is it to tell powerful figures in politics that it’s time to resign? In 2024, these are familiar questions. Elderly members of Congress and Supreme Court justices alike have resisted calls to retire; Senator Dianne Feinstein and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg both died in office. For much of this year, our politics has been dominated by octogenarians, including Mitch McConnell, Nancy Pelosi, and Chuck Grassley (who, at the age of 91, is actually a nonagenarian). But Joe Biden’s decision to run for reelection at the age of 80 was the strongest case against the gerontocracy.

Despite growing signs that Biden was in decline, the White House remained firmly in denial—at least until the disastrous presidential debate in June. Last week, The Wall Street Journal reported in detail how Biden’s staff formed a protective phalanx around the frail president, tightly controlling access, scripting interactions with his Cabinet, and scheduling meetings around his “bad” times. (The White House denied that the president’s schedule “had been altered due to his age.”) “Interactions with senior Democratic lawmakers and some cabinet members—including powerful secretaries such as Defense’s Lloyd Austin and Treasury’s Janet Yellen—were infrequent or grew less frequent,” the Journal reported. “Some legislative leaders had a hard time getting the president’s ear at key moments, including ahead of the U.S.’s disastrous pullout from Afghanistan.” All the while, the White House pushed back against evidence that Biden—the oldest man ever to serve as president—might be unable to effectively serve for another four years.

America’s politicians have an age problem, and the issue seems especially acute among congressional Democrats. The prevalence of older politicians can arguably make the elected class less relevant to younger voters and make it more difficult for new voices to rise in politics. But at its core, this is an issue of honesty: Didn’t the American people have a right to know that Biden was struggling? Didn’t Texans deserve to know about Granger? And if either of them was being lied to by those supporting them, didn’t they themselves deserve the truth too?

Eventually, Biden did bow out—and one consequence is that the next president of the United States will, like Biden, be 82 years old at the end of his term.

Related:

- Why do such elderly people run America? (From 2020)

- You’ll miss gerontocracy when it’s gone, Franklin Foer argues.

Here are four new stories from The Atlantic:

- New York City has lost control of crime.

- How tortillas lost their magic

- Not the life Matt Gaetz was planning on

- Mark Leibovich on the politics of procrastination

Today’s News

- President Biden commuted the sentences of almost all of the prisoners currently on federal death row. Thirty-seven prisoners, all of whom were convicted of murder, will serve life in prison without the possibility of parole.

- The Jordanian foreign minister and the Qatari minister of state arrived in Damascus to meet with Syria’s new leadership.

- At a rally yesterday, Donald Trump said that his administration could attempt to regain control of the Panama Canal. The remark prompted a response from Panamanian President José Raúl Mulino, who said that “every square meter of the Panama Canal belongs to Panama.”

Dispatches

- Work in Progress: California raised the minimum wage for fast-food workers—and employment kept rising, Rogé Karma writes. So why has the law been proclaimed a failure?

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

Dear Therapist: How Do I Deal With My Hostile Sister?

By Lori Gottlieb

This holiday season, I’ve been navigating some major challenges with my older sister and my boyfriend. The difficulty started last winter, when my boyfriend wanted to buy an investment property in the state where I’m from and my sister currently resides. My sister became very upset with me and my boyfriend for investing in a place where she lives. We received angry phone calls and disparaging text messages from her. We were shocked at her response. I have yet to make up with my sister as she never apologized, but I have been cordial with her when around the rest of our family.

More From The Atlantic

- Martin Short deserved better.

- The “anthropological change” happening in Venezuela

- Two different ways of understanding fatherhood

- The hysterical crypto bubble somehow became respectable.

Culture Break

Read. These six books are perfect for reading by the fire while the days grow imperceptibly longer.

Look. This year, The Atlantic’s art department created and commissioned thousands of images to support the magazine’s journalism. Here are some of their favorites.

Isabel Fattal contributed to this newsletter.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What's Your Reaction?