America the Air-Conditioned

Cooling technology has become an American necessity—but an expensive one.

This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

As a heat wave spreads across America, the whirring of air conditioners follows close behind. AC has become an American necessity—but at what cost?

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

- The rise of a new, dangerous cynicism

- David Frum: The most dangerous bias in today’s America

- J. D. Vance makes his VP pitch.

The Cost of Cooling

It’s going to be a really hot week. Americans across the country are feeling the full force of the “heat dome,” with temperatures creeping toward 100 degrees—and humidity that makes it feel even hotter. About 80 million Americans, largely on the East Coast and in the Midwest, are under extreme-heat alerts. Record-breaking heat has already descended on the Southwest this year: In Phoenix, temperatures rose to 113 degrees earlier this month (nearly a dozen people fainted at a Trump rally there).

A single piece of technology has made recent heat waves safer and more bearable than they’d be otherwise. The trusty air conditioner doesn’t just cool us off—it has shaped the way we live in America, my colleague Rebecca J. Rosen wrote in The Atlantic in 2011. AC changed home design and reoriented workdays; it even arguably influenced the way that Congress operates, by expanding the legislative calendar into the summer. Robust at-home cooling helped make living in fast-growing regions such as the Southwest more appealing—and that region has reshaped American politics and life. (One author even credits AC with getting Ronald Reagan elected.)

It wasn’t always this way. In the early 20th century, AC was generally reserved for public spaces; around 1940, well under 1 percent of American homes had AC. But in the decades that followed, the technology found its way into more households. By 2001, about 77 percent of homes had AC. Now some 90 percent of American homes use air-conditioning, according to a 2020 federal-government survey. AC was once seen by many Americans as a nice-to-have, rather than a necessity. But in recent decades, Americans have experienced an attitude shift: Pew polling found that in 2006, 70 percent of people considered AC a necessity, compared with about half who viewed it that way a decade earlier. And the country has only gotten hotter since then.

AC units and the energy required to power them can be quite expensive, presenting a real burden for many people: 27 percent of Americans said they had difficulty paying energy bills in 2020. Still, people across income brackets rely on AC: Households making more than $100,000 are only moderately more likely to have AC than those making less than $30,000. (Globally, according to one estimate, only about 8 percent of the nearly 3 billion people in the hottest regions have access to AC.) The prevalence of AC in the U.S. does vary by region: More than half of homes in Seattle and San Francisco were without AC in 2019, according to census data. But heat waves are pushing more and more residents to plug in.

The environmental cost of air-conditioning puts users in an impossible predicament. The United Nations warned last year that global energy used for cooling could double by 2050, and that it could make up 10 percent of the world’s greenhouse-gas emissions at that point. At least until more efficient cooling is widespread, AC will contribute to the rising heat that makes it essential.

The risks of heat are real: Hot weather kills more people than other weather events, and heat-related deaths have risen dramatically by the year. Efforts to enshrine heat protections for workers are under way in some places—but they have not always gone over well. Fewer than 10 states have any sort of workplace heat protections in place, and notably absent from the list are some of the most scorching states. In some cases, that’s a choice made by lawmakers: Earlier this year, Ron DeSantis blocked an effort to pass heat-safety measures for laborers in Florida. Still, the Biden administration is expected to propose the first federal legislation addressing heat in the workplace in the coming months.

AC was key to the development of America in the 20th century. As Rebecca notes in her article, “The suburban American dream was built on the sweat of air conditioners.” The sweltering America of the future may rely on the units for its survival too.

Related:

Today’s News

- The Biden administration announced a new plan that will clear a path to citizenship for some undocumented spouses of U.S. citizens. Those who qualify will no longer have to leave the country to secure permanent residency.

- Russian President Vladimir Putin arrived in North Korea for the first time in 24 years and met with the country’s leader, Kim Jong Un. They discussed strengthening their nations’ partnership and countering the global influence of the United States.

- The bipartisan House Ethics Committee expanded its investigation into Representative Matt Gaetz, who is accused of sexual misconduct, illegal drug use, and accepting improper gifts. Gaetz has denied the allegations.

Dispatches

- The Weekly Planet: No amount of adaptation to climate change can fix Miami’s water problems, Mario Alejandro Ariza writes.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

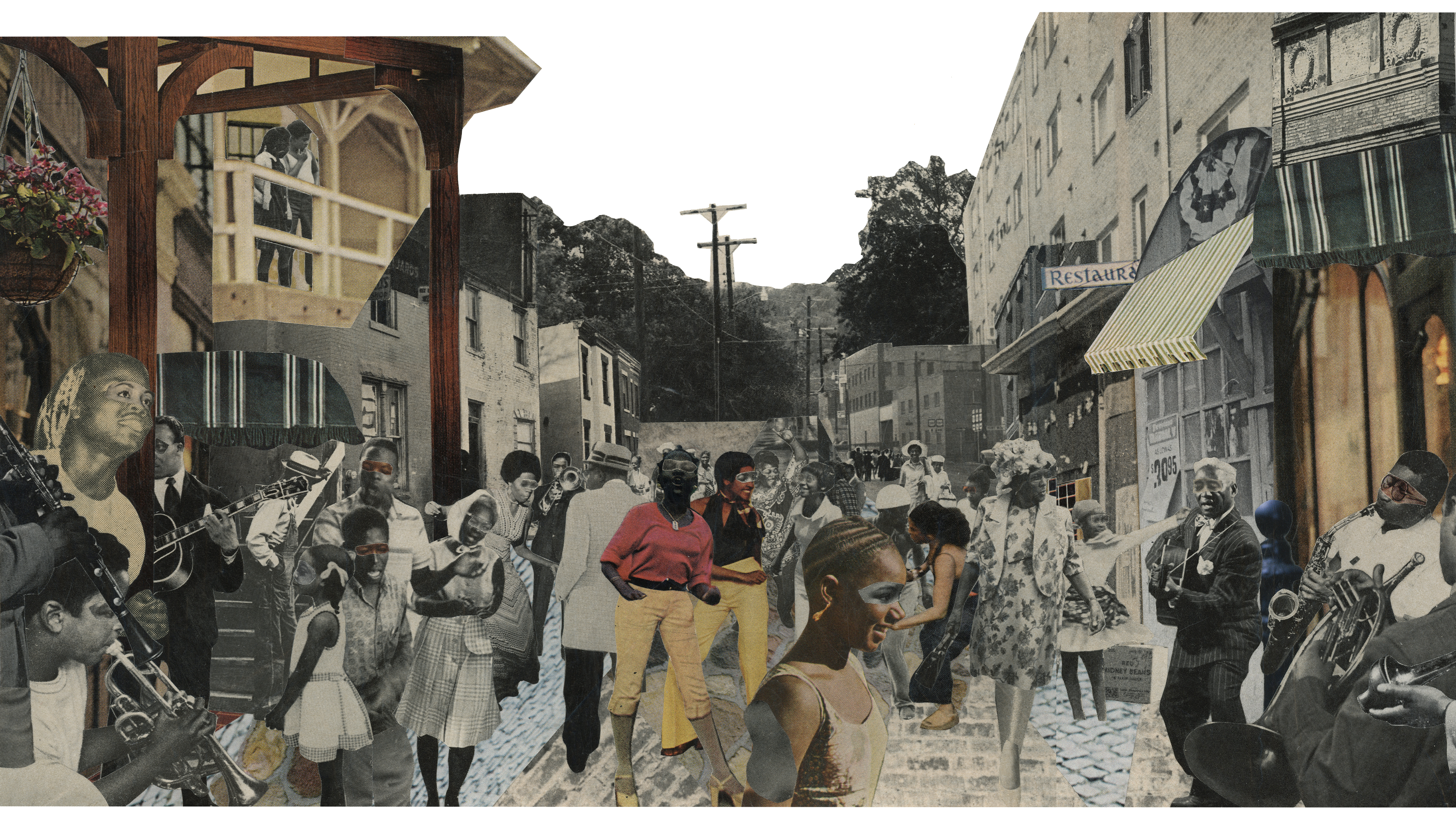

Before Juneteenth

By Susannah J. Ural and Ann Marsh Daly

Juneteenth—sometimes called America’s second Independence Day—takes its name from June 19, 1865, when the U.S. Army in Galveston, Texas, posted a proclamation declaring the enslaved free. In 1866, Black Galvestonians gathered to commemorate the date of their freedom, beginning an annual observance in Texas that spread across the nation and became a federal holiday in 2021. But the slender volume in the Mississippi museum, and the summer-long celebrations in New Orleans that it records, invites us to realize that Juneteenth was a national holiday from the start.

More From The Atlantic

- Good on Paper: Who really protests, and why?

- Why are more athletes running for office?

- The new calculus of summer workouts

- Why American newspapers keep picking British editors

- Instagram is not a cigarette.

Culture Break

Listen. The new episode of How to Know What’s Real asks if we have, as a culture, fully embraced the end of endings.

Read. “Mojave Ghost,” a poem by Forrest Gander:

“Looking for their night roost, tiny / birds drop like stars into the darkened dead trees / around me.”

P.S.

I’ll end on a totally unrelated note, but maybe it will take your mind off the heat: Having seen Illinoise on Broadway last week—a new show featuring the songs of Sufjan Stevens, choreography by Justin Peck, and a dialogue-free plot by Jackie Sibblies Drury—I was interested to read this analysis of how many Broadway hits this season are rooted in pop music. Apparently, more than half of the new musicals that opened on Broadway this year feature scores by artists with backgrounds in the music industry, including Barry Manilow, Britney Spears, David Byrne, and Alicia Keys. As the New York Times reporter Michael Paulson notes, “In some ways, this is an everything-old-is-new-again phenomenon. In the early 20th century, figures like Irving Berlin and Cole Porter found success both onstage and on the radio.” But now that so many mainstream artists are also writing scores, he writes, “what was once a trickle … is becoming a flood.”

— Lora

Stephanie Bai contributed to this newsletter.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

What's Your Reaction?