A single genetic tweak caused human ancestors to lose their tails 25 million years ago — but it came at a cost

Researchers believe it could be behind a birth defect called spina bifida that still affects babies today.

Sebastian Kaulitzki/Science Photo Library/Getty Images

- Scientists have found a mutation in our DNA that snipped our tails off.

- The mutation may have allowed our ancestors to walk upright.

- But it may also be behind a birth defect that still affects babies today.

We may have finally figured out why we begin developing tails in the womb — and why we lose them at around eight weeks of gestation.

A single genetic tweak that occurred among our ancestors 25 million years ago means humans today are unable to grow a tail, according to a new study.

This tweak to our genetic makeup may have given us evolutionary advantages, such as being able to walk upright — but it came at a cost.

Researchers believe it could be behind a birth defect called spina bifida that still affects babies. Himanshu Sharma/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

A long-standing mystery

Humans' ancestors started off with a tail, but about 25 million years ago, they dropped the appendage, leaving it to other tree-dwelling primates like monkeys.

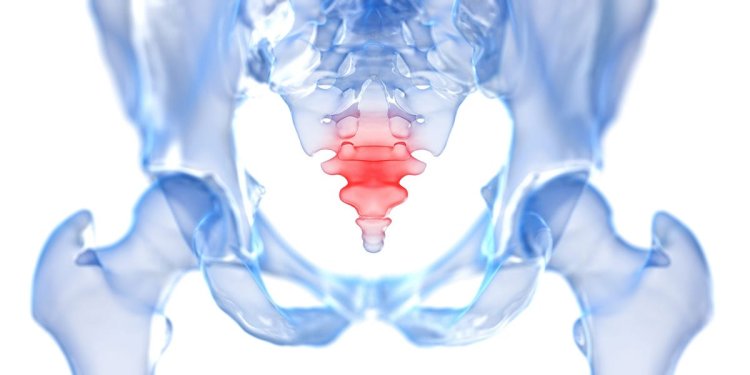

But it's not like we've completely lost the ability to make a tail. Human fetuses start growing a tail in the womb, but after about eight weeks they lose it leaving behind only the coccyx, a nub at the end of the spine where the tail used to be.

That we still have the genes to make a tail, but our bodies refuse to make it, has long puzzled scientists.

Scientists knew that a gene called TBXT was involved in the snipping of the tail. Mutations to this gene are linked to shortened tail phenotypes in tailed animals. It's what gave us the Manx cat, a breed of cat without a tail, for instance.

But they couldn't figure out why our genetic makeup made us tail-less. A team of scientists at the NYU Langone and Grossman School of Medicine say they have finally cracked it. Asep Supriatna/Getty Images

Wandering DNA snipped off our tails

The solution, they found, was in a type of "jumping gene" called an Alu element. These types of DNA sequences are known for moving around the genome.

Scientists found two Alu elements around a part of the TBXT gene, called Exon 6. The insertion of these DNA sequences seemed to result in the loss of a tail.

Scientists tested their findings by inserting Alu sequences in mice. They found they sometimes had shortened tails or no tails at all. Xia, B et al. Nature (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07095-8 CC BY 4.0

It's still not clear exactly how the mutation leads us to be tail-less, Miriam Konkel and Emily Casanova, two experts who commented on the work but were not involved in the study, said in an opinion piece in Nature.

There could still be other factors at play in the formation of a tail that could be working with the Alu elements in the TBXT gene.

Still, the work is "deeply compelling" and offers "a new chapter in the tale of our tail," Konkel and Casanova said.

Their findings were published in the peer-reviewed journal Nature on February 28. A version of the study, published before it passed the scrutiny of peers, was previously published on the online server arXiv in 2021.

A missing tail that comes with a cost

While the work provides an unprecedented look into why humans are the way they are, it also exposes a sinister shadow of the mutation.

Scientists found that adding the Alu sequences to the TBXT gene in mice didn't only truncate their tails, it also gave them an unusually high level of a defect in the neural tube, a structure which later turns into the nerves in the spine and the brain.

In humans, that defect is known for producing spina bifida, which is when the baby's spinal cord doesn't completely close, leaving a bit of the spine and some nerves exposed on the back. This can lead to paralysis or incontinence. It is fairly common, affecting about one in 2,000 births in the US every year.

Some scientists argue that it was a necessary sacrifice in our quest to stand up. They say, for instance, that a tail would have hindered the delicate balance that keeps us on our feet.

Others, however, aren't sure it's that simple. Xia, B et al. Nature (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07095-8 CC BY 4.0

Early research now suggests we may have lost our tails while we were still in trees, and that a tail could have helped, rather than hindered, our two-legged lifestyle, said Konkel and Casanova.

It's possible, these scientists say, that the mutation arose when humans' and apes' ancestors were isolated from other groups. They claim the loss of the tail was less of an evolutionary boon as it was a bizarre trait our ancestors kept because they didn't mix with primates with tails at the time.

"We apparently paid a cost for the loss of the tail, and we still feel the echoes," Itai Yanai, a study author and graduate researcher at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, previously told Science magazine.

"We must have had a clear benefit for losing the tail, whether it was improved locomotion or something else," said Yanai.

What's Your Reaction?