A Campus Novel With Actual Stakes

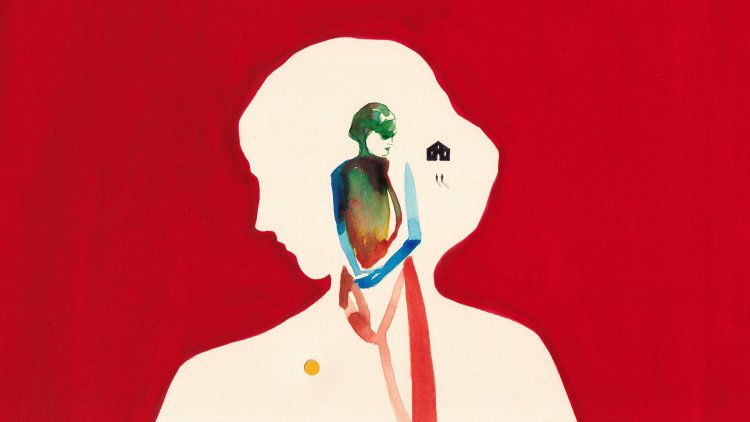

Karla Cornejo Villavicencio’s debut work of fiction captures the paradox of immigrant identity in the United States.

In today’s United States, at least in liberal and leftist circles, certain aspects of identity are understood to be a matter of choice—as well as a battleground for freedom. I don’t live in America anymore, but over the course of the decade I spent there, I learned that a person’s decision to identify as Tejano, Chicano, or Latine, rather than as Texan, Mexican American, or Hispanic, has philosophical and political implications that reach far beyond semantics. What complicates the picture is that, in order to be who we are, we need others to recognize us—to see us as we see ourselves and accept us as such. Or, if you prefer memes to Hegel, you could say that the problem of identity is that we live in a society. And in most societies, if you belong to a marginalized group, those in power may make decisions that further diminish your standing.

This struggle for recognition is at the center of Karla Cornejo Villavicencio’s first work of fiction, Catalina, an often delightful and occasionally unsatisfying campus novel about a Latine senior at Harvard who thinks about books, boys, and clothes; worries about her working-class immigrant grandparents; has a complicated relationship with the country where her ancestors are buried; rolls her eyes at what she sees as white people’s endless capacity for foolishness; and dreams of becoming a writer. Everything about Catalina, in other words, is a product of the United States: Few things are more American than an overachieving immigrant striver.

And yet, according to the United States and its laws, Catalina is not American. Born in Ecuador, she was sent to live with her grandparents in New York when she was very young, after she miraculously survived the car crash that killed her parents. The problem is that Catalina and her new guardians are undocumented residents. Cornejo Villavicencio’s novel, then, is a meditation on an aspect of identity that is not a question of choice: nationality. It doesn’t matter that Catalina identifies as American rather than Ecuadoran. She could change any number of things about herself, but she can do nothing to alter the fact that she was born outside the arbitrary boundaries of the country she calls home.

Read: There’s no such thing as a meaningful death

The only two exits from this predicament, Catalina soon learns, are equally treacherous. The immigration lawyer who gives her a pro bono consultation at Harvard’s behest tells her that her paths to changing her undocumented status are either “marriage or legislation.” This collision between love and the law distinguishes Catalina from other recent campus novels, many of which struggle to find depth in the banal incidents of a student’s coming of age. Assuming no imminent development in legislation, Catalina would have to get married to an American citizen. But when love becomes a vehicle for enfranchisement, it ceases to be just love. Catalina’s problem isn’t that the personal is political—it always is—but that, for many immigrants, the political is personal, even intimate.

This tension, however, plays out mostly in the background of the novel. Catalina is generally more concerned with the usual preoccupations of undergraduates: her complicated friendship with a fellow student, an invitation to join an “arts and letters secret society,” the outfit she’ll wear to the next party, and, above all, boys. There are many of them, she tells us, without a trace of shame. Her pickup line is at once ridiculous and a welcome rebuke to the commonplace notion that women like her are inevitably victims of their culture’s supposed repression of female sexuality: “I can be devastating in bed.”

But Catalina is also self-aware enough to understand that the boys who interest her are, in truth, just an “audience” for the personality she’s trying out. And indeed, Cornejo Villavicencio’s fluid, digressive prose shines brightest when Catalina’s theatrical self-presentation takes center stage. Consider the scene in which she meets the boy who later becomes a main character in her life. Catalina has just run out of the campus museum where she works to let her grandmother know that she has won a writing prize. The boy in question, Nathaniel, who is white, is smoking nearby. While Catalina speaks animatedly in Spanish with her grandmother, the two lock eyes. When she hangs up, he approaches her:

“What did your mother say?” he said, putting out his cigarette under the toes of his Nikes.

“What makes you think it was my mother?”

“How you spoke to her just now, it had to be an older person and I don’t see you cursing out your grandma.”

Having spent my formative years in the U.S., I know something about the electric thrill of discovering that an American object of desire understands your mother tongue. But just when I thought I was about to watch Cornejo Villavicencio’s protagonist fall into the volatile tangle of erotic and linguistic misrecognition that shook me so much that I wound up writing a novel about it, Catalina turns out to be far shrewder than I was at her age:

I could tell he wanted me to be impressed. He wanted me to ask him how he knew Spanish, but I was not curious, because there were a finite number of explanations for a boy such as him at a place such as this, and I felt no interest in exploring the known world.

Catalina exchanges a few lines with Nathaniel about a class they took together freshman year. And then, out of nowhere, Cornejo Villavicencio delivers irrefutable proof that, when it comes to depicting courtship, she is a worthy student of Gabriel García Márquez:

“Could you tie my shoe?” I said suddenly, my voice breaking slightly. I cleared my throat. “I don’t think I can kneel in this dress. It’s too short” …

Nathaniel widened his eyes but knelt anyway.

“So you just say things, sometimes?” he asked, tying the laces on my white leather Oxfords, shoes my grandmother bought specifically so I could wear them to parties with boys. “Like, you say whatever you want? Because it amuses you?”

His words were angry but his face was wild with happy things in it.

Catalina’s boldness has the unmistakable flavor of realism: This is what late-adolescent desire is like. The scene is specific and for that reason vivid, giving the reader a glimpse of what makes each character unique. On top of everything, the whole conversation is, well, kind of hot.

The specificity of the scene I just recounted, however, heightened the disappointment I felt each time Catalina falls prey to stereotypical characterizations of people she encounters. At one point, looking around at the other Latines in an anthropology class, she says that she “had forgotten what we looked like.” A few pages later, though, Catalina notes that her Puerto Rican friend Delphine’s widowed father “was Black. Not African American. Afro Latino.” By contrast, Delphine’s deceased mother, also Puerto Rican, had “pink skin, pink cheeks, green eyes, curly dark hair.” Latines, of course, look as different from one another as Delphine’s parents do from each other. At the risk of repeating the commonly expressed skepticism regarding the coherence of the very notion of latinidad, I have to ask: What do “we” look like?

[Read: The fundamental paradox of latinidad]

Then again, it could be that Catalina’s reliance on stereotypes is a symptom of her struggle with a world that lets those reductive perceptions, rather than people’s actual qualities, determine who they can be. Early on, Catalina says that she and Delphine “looked like two characters from the same cartoon animator.” Perhaps Cornejo Villavicencio is more astute than her protagonist. Perhaps this is a novel about a young woman so overwhelmed by American racism that she can’t help describing herself and her Latina friend as identical caricatures. Such is the paradox of identity in the contemporary United States: If marginalized people want to be seen—which is to say, recognized—they sometimes have to become stereotypical.

Cornejo Villavicencio first became known for her nonfiction debut, The Undocumented Americans, a collection of essays that blends personal narrative with reported profiles of some of the most vulnerable immigrant workers in the United States, and which was a finalist for the 2020 National Book Award. That book’s emphasis on the marginalized among the marginalized, she explained, was an attempt to shift the discussion about immigration away from so-called Dreamers—young and often accomplished undocumented people who were brought to the U.S. as children—and toward their parents. Day laborers and domestic workers, Cornejo Villavicencio argued, are just as deserving of social recognition and legal relief as are their photogenic offspring, including those who, like herself, beat the odds of America’s rigged meritocracy to earn admission to places such as Harvard.

Cornejo Villavicencio has said that she began writing The Undocumented Americans shortly after the election of Donald Trump. The book is indeed a faithful testimonio, as we would say in Latin America, of that moment of political despair. By then, chances of the DREAM Act—a proposed law that would have provided Dreamers with a path to citizenship—passing had all but dried up, and the notion that Congress would ever approve more comprehensive immigration reform seemed hopelessly naive. Even Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, an Obama-era policy that protected Dreamers from the immediate threat of deportation and allowed them to seek formal employment, was at risk. Cornejo Villavicencio’s prose from that period crackles with righteous anger at a country that was subjecting people like her parents and herself to a regime of terror, most notably by separating children from their families at the border, and then imprisoning those children in crowded chain-link cages in “detention centers.”

The presidency of Joe Biden has not been much kinder to migrants, but it does seem to have given Cornejo Villavicencio space to consider less urgent questions, such as the political dilemmas of those undocumented immigrants whose lives are, relatively speaking, less precarious. Catalina believes that “people who were politically neutral were cowards,” but she is also acutely aware of the dwindling prospects of the DREAM Act, an awareness that leads her to a kind of paralysis. Graduation is approaching, but what’s the point of writing a good thesis if her immigration status shuts her out of most desirable jobs? Her malaise is so intense that she can barely bring herself to join the organizing efforts of other Dreamers at Harvard.

But then, near the end of the book, her grandfather receives a deportation order. Desperate, Catalina does what Ivy Leaguers learn to do when they need help: She emails the most famous person she knows, Nathaniel’s father, Byron Wheeler, a celebrated filmmaker who makes artsy documentaries about Latin America. After he suggests, half-jokingly, that she should marry Nathaniel, Catalina and Byron come up with a plan: They will make a short film about Catalina’s graduation from Harvard to call attention to her grandfather’s case.

Catalina is less than thrilled about the prospect. “I don’t think I have it in me to be a poster child,” she tells Byron. “I want to sell out and work for a hedge fund like everyone else.” It’s not just her. When she shows footage from the documentary to Delphine, her friend replies that she’s “a little concerned it comes across as stereotypical.” But Catalina loves her grandfather enough to put aside her ambivalence. With this development, Cornejo Villavicencio seems to suggest that, in a country as obsessed with identity as the United States is, transforming into stereotypes allows the marginalized to not only become visible but also acquire agency. Perhaps one must subsume one’s uniqueness into the unspecified “we” that Catalina evokes when she finds herself surrounded by other Latines in the classroom—and give up individual identity for the sake of a political identity, one that offers a measure of power.

Could this discovery mark the culmination of our hero’s coming of age? Not quite. After a flurry of events that feels rushed, almost as if it were the outline of a longer book, the novel suddenly ends. The documentary never gets finished. The grandfather’s predicament comes to an unexpected conclusion that leaves his granddaughter feeling bitter. The DREAM Act fails to pass. Catalina and Nathaniel never get married. It’s unsatisfying, even disappointing. But perhaps this abruptness is intentional. I choose to believe that Cornejo Villavicencio wants to leave the reader hanging. Until the United States recognizes undocumented Americans, there will be no rest for the likes of Catalina—or for the readers of her story.

What's Your Reaction?